“If I see other kids going to school, I cry,” said 16-year-old “Anesu” as she spoke with Human Rights Watch last year in Mashonaland Central, Zimbabwe. “I dropped out when I was in form 2. There was no money for school fees.”

Before she dropped out, Anesu, whose name I changed to protect her privacy, said she had to walk two hours each way to get to the nearest secondary school. “It was a long distance. My legs were beginning to pain me. It was another reason I dropped. There was no other school close by.” She began working six days a week on tobacco farms, earning US$3 a day. But she dreamed of going back to school.

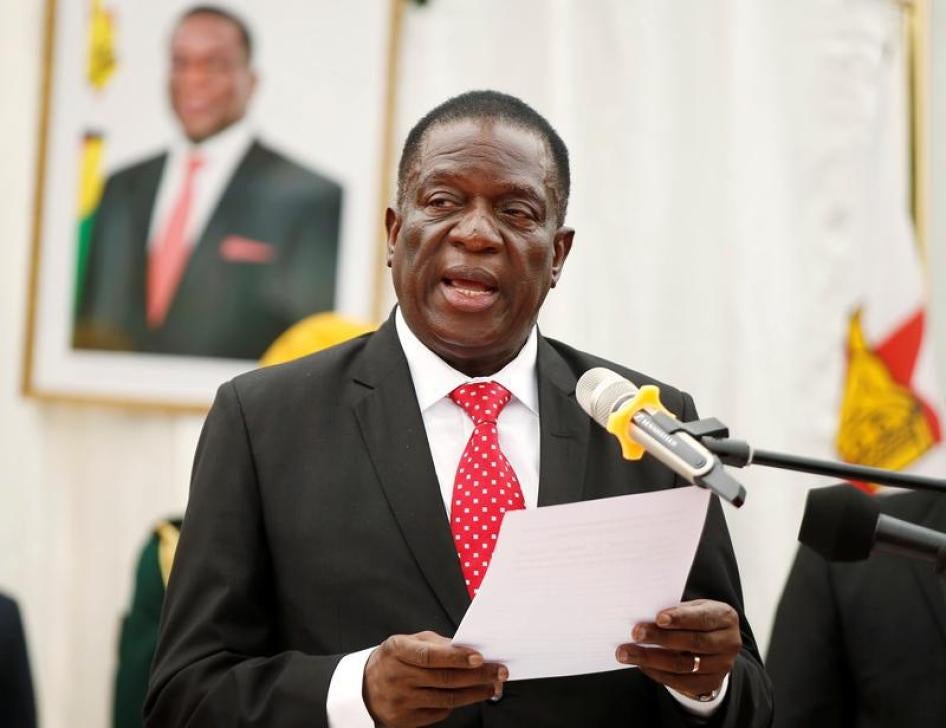

Anesu’s story is not unique. In 2016 and 2017, Human Rights Watch spoke to more than 100 people about access to education in Zimbabwe. They described many barriers that make it difficult for children to stay in school. President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his newly appointed primary and secondary education minister, Paul Mavima, have an opportunity to help Zimbabwe’s children by breaking down these barriers.

While Zimbabwe’s 2013 constitution requires the government to promote “free and compulsory basic education for children,” the reality on the ground shows that it doesn’t. UNICEF reports that even though overall enrollment has increased in Zimbabwe, more than 1.2 million children of school-going ages 3 to 16 are out of school.

Many families have to pay fees or levies for their children to go to public schools. Nearly everyone Human Rights Watch spoke with said they have a hard time paying those fees, and many said the fees were prohibitively expensive, particularly for secondary school. Families told us that primary school costs US$10 to $15 per term, and secondary school sometimes costs close to $150 for the first term, and $35 to $50 for subsequent terms. Books and uniforms are an additional expense.

The government’s Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) program provides financial assistance to some families for children’s education costs, but the program is underfunded and many children who need help are not getting it.

Some people told us that school administrators sent children home, or refused to provide end-of-year exam results, if school fees weren’t paid. One small-scale farmer and father of four told us his children were sent home from school several times a week one term when he was behind in paying the fees.

“For that term, the children don’t learn well because they are constantly being sent home,” he said. “It affects their [academic] results. They won’t be in class when others are learning.” The government adopted a policy that children should not be sent home for nonpayment of school fees, but a 2017 report found at least 63 percent of children had at some point been sent home from school for that reason.

But the cost is not the only problem. Like Anesu, many children have to travel long distances to school. One 14-year-old boy told us it took him one hour each way. “But I run,” he said. “If I walked, it would take one and a half or two hours.”

And many schools use corporal punishment, which can be humiliating, especially for adolescent girls. Children described being beaten by teachers for arriving late, missing class, or misbehaving. Children said they or other students were beaten with sticks on their hands, arms, legs, or backs, or slapped across the face. “We were beaten for being absent,” said one 15-year-old girl, saying her teacher made her put her head through the open back of a chair, and then beat her on the back with a stick.

One young man, age 18, said: “They used to beat us. If they came into the classroom and there was a lot of noise, they would hit everyone with a stick. A very painful stick that is not suitable to beat anyone. That’s why some children drop out of school, because they fear being beaten.”

In 2017, the High Court of Zimbabwe ruled that corporal punishment for children was unconstitutional. Putting a ban on corporal punishment into effect is essential to protect children from violence in schools.

President Mnangagwa has pledged to rebuild Zimbabwe despite the country’s continuing economic problems.

Quality education can lift families and communities out of poverty and increase a country’s economic growth. As the 2017 school year ends, and the 2018 school year begins, Mnangagwa, and minister Mavima, have a key opportunity to address barriers to education. The new government should abolish school fees, enforce the prohibition on corporal punishment, and increase access to quality education for Zimbabwe’s children.