EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

Committee on Development Subcommittee on Human Rights Joint Debate

Human Rights Situation in Ethiopia: Need for Stronger EU Action October 12, 2016

Testimony of Felix Horne, Senior Ethiopia/Eritrea Researcher, Human Rights Watch

Thank you for this opportunity to speak to parliament today at a critical time – both for Ethiopians and for the EU’s relationship with Ethiopia.

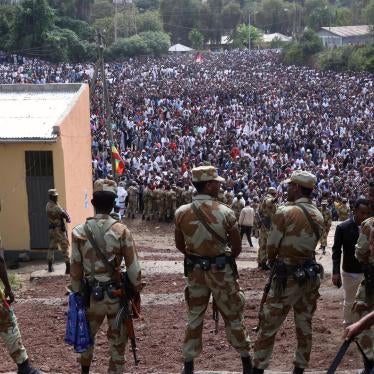

On October 2, in Bishoftu, Ethiopia, an unknown number of people, possibly hundreds, died during a stampede after security forces used teargas and gunfire to control a tense crowd at the annual Irreecha festival. Irreecha is an important cultural event for the Oromo ethnic group and draws millions of people each year to Bishoftu. The deaths have exacerbated pre-existing anger and frustrations throughout Oromia. Since that terrible day, there have been more anti-government protests and destruction of government buildings and properties. On Sunday, October 9, Ethiopia’s prime minister declared a six-month state of emergency.

The tragic events at Irreecha came after 11 months of anti-government protests in many parts of Oromia. Protesters initially were concerned that a proposed new master plan for the capital, Addis Ababa, would lead to further displacement of Oromo farmers, something that had happened with regularity in previous years. By the time the government announced the cancellation of the master plan in January, protester grievances had expanded to include condemnation of the brutality of the security forces’ response to the largely peaceful protests as well as decades of marginalization and human rights violations of the Oromo people.

In July, large protests also occurred in the Amhara region over complex questions of ethnic identity and the dominance in economic and political affairs of those with ties to the ruling party. The government’s brutality continued. In August in Amhara and Oromia regions, security forces killed over 100 people in one bloody weekend.

As protests have unfolded, Human Rights Watch interviewed several hundred individuals from more than 80 locations across Ethiopia. We were able to document how security forces used excessive and unnecessary lethal force and killed at least 500 protesters, and detained tens of thousands, often without charge. Released detainees told us of widespread mistreatment and torture.

At this point, Ethiopia is in the midst of its worst political and human rights crisis since the government of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front came to power in 1991. Urgent action is needed before the crisis further deteriorates. While Ethiopian people bravely demand their human rights, concerned intergovernmental bodies and governments should press the Ethiopian government to respect basic rights and hold accountable those who violate them. The EU should be leading the way.

The recent events were a long time in the making. They are the outcome of the government’s systematic and calculated suppression of fundamental rights and freedoms that have closed political space and left few opportunities for the peaceful expression of dissent.

Ethiopia is among Africa’s leading jailors of journalists, and there is little space for independent journalists to operate. Ethiopian journalists and bloggers must choose between self-censorship, arrest, or living in exile. Websites critical of the government are blocked, radio stations are regularly jammed during sensitive times, and those providing information to journalists are often targeted for arrest. At various times in the last three months, the government has blocked the internet completely in some locations, restricted access to social media, and jammed radio transmissions including German broadcaster Deustche Welle. Bloggers have been arrested, and international journalists continue to report restrictions on access to the country. As we speak, the government is blocking access to the internet in many parts of Oromia.

Independent civil society groups face similar overwhelming obstruction. In 2009 the government passed the Charities and Societies Proclamation, which severely curtails the ability of nongovernmental organizations to work in areas of human rights and good governance. The anti-terrorism law, passed in 2009, has been used to crack down on peaceful expressions of dissent. Many opposition politicians, journalists, and activists have been convicted under that law and sentenced to prison terms. Courts have shown little independence in politically charged trials. There have also been serious restrictions on opposition political parties, which led to the ruling coalition in the May 2015 election to win 100 percent of the seats in the federal and regional parliaments, despite evident anti-government feelings in much of the country, as the protests indicate.

The authorities restrict public protests with routine denial of permits and arrests of real or perceived protest organizers. Fear of opposing the government has historically kept people from protesting, but that fear is rapidly dissipating. For those who do take to the streets, as thousands have done in hundreds of locations over the last year, brutal force from security forces is often the response. What avenues does this leave to express dissent, to question government policies or to voice concern over abusive practices?

The ruling party has dealt swiftly and aggressively with anyone who challenges the government narrative. For example, in March 2015, Pastor Omot Agwa was arrested in Addis Ababa with six other colleagues after trying to attend a food security workshop in Nairobi. Four of them were released, but Pastor Omot and two other colleagues have now been charged with terrorism, accused of belonging to a long inactive armed opposition group. Several months earlier, he had been the translator for the World Bank Inspection Panel complaint into the villagization program in western Ethiopia’s Gambella region. Human Rights Watch and others documented how the villagization program was associated with forced displacement of indigenous people leading to worsening food insecurity and several thousand people fleeing into neighboring countries. The program was funded, albeit indirectly, through the World Bank, the EU, and others. While it’s impossible to say whether the charges against him are linked to his role as translator, his case is typical of those that attempt to question the government’s policies, particularly on sensitive topics like development.

Human Rights Watch has also documented the Ethiopian government’s misuse of development assistance, including some EU funding, by ensuring that only those who are ruling party members or supporters receive the benefits of aid, including access to fertilizers, to seeds, to jobs, and to training opportunities. We first documented this in 2010, and there is little evidence that any action has been taken by the EU to monitor the negative and partisan impact of development assistance to Ethiopia. Concerns over the political capture of aid continue to come up regularly in our research. While EU development assistance makes an invaluable contribution to much-needed poverty reduction efforts in Ethiopia, it also has the unintended side effect of increasing the government’s repressive capacity, by contributing to the reliance that Ethiopians have on the government for their livelihoods and ultimately for their survival.

The EU has employed quiet diplomacy with Ethiopia in response to the dramatic deterioration in the human rights situation that has contributed to the current crisis. Turning a blind eye to the government’s repressive actions is undermining the EU’s priorities in the Horn of Africa and putting partnerships at risk, including in development assistance and migration. While the EU’s approach has been counterproductive in dealing with human rights, there have been some positive steps taken.

In January, this parliament passed the strongest resolution in many years on Ethiopia. Many hoped that this would lead to a shift in policy from the EU, but so far that hasn’t happened.

We therefore call on you today, in close coordination with your national parliament counterparts, to use every opportunity to press the EU and its member states to take strong and urgent action to try to prevent an irreversible and worsening crisis in Ethiopia. In the content of sweeping abuses of free expression, assembly and association, the recently announced state of emergency should prompt urgent questions regarding the government’s plans for implementation. Under international human rights law, governments need to ensure that any measures to restrict freedom of expression and association are “strictly required by the exigencies of the situation” and strictly proportionate to the aim pursued. Importantly, emergency powers must never be applied in a discriminatory manner, nor stigmatize people of a particular ethnicity, religion, or social group.

In the short term there are three critical actions for the EU:

- The EU should continue to push for an international investigation into the brutal crackdown in Amhara and Oromia regions since November 2015 and the recent deaths in Irreecha. The EU statement at the UN Human Rights Council session in September was a positive first step in pushing for this. The EU should also be pushing for Ethiopia to invite the UN special rapporteurs and other special procedures, 11 of whom have outstanding requests for access to the country. Ethiopia has not permitted a UN special rapporteur access since 2007, except for the special rapporteur for Eritrea.

- The EU should publicly call on Ethiopia to release of all those arbitrarily detained during the protests, including opposition leaders such as Bekele Gerba. Bekele was the deputy chairman for the Oromo Federalist Congress and a staunch advocate for non-violent approaches to address Oromo grievances. He was arrested in December 2015 and charged under the antiterrorism law. Being a peaceful and outspoken critic of the current government should not be defined as terrorism.

- The EU should publicly press for the lifting of government restrictions on the right to freedom of information and expression, including on the internet and social media, as well as the jamming of lawful broadcasts. The government should promptly release bloggers and journalists detained for the peaceful exercise of their free expression rights.

Thank you.