Elisa G. had her period when the immigration detention center in Arizona where she was confined locked down her entire housing unit for three days. She appealed to an immigration officer for more sanitary pads and a chance to take a shower. The officer gave her only two pads—not enough. Without anything else to use, she told Human Rights Watch, “I had to just sit on the toilet for hours because I had nothing else [I could] do.”

Elisa’s story is a small part of a much bigger issue. Millions of women around the world lack access to adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene, with a negative impact on their lives.

Everyone needs water to survive. Yet, women and girls have particular biological needs for water, sanitation, and an enabling environment for good hygiene—such as clean and sufficient water for childbirth and post-partum care or to manage menstruation—that require accommodation for women and girls to realize their human rights.

When schools lack private bathrooms and sanitation facilities, girls may need to go home to manage their menstruation, losing instruction time. Girls’ inability to manage these needs adequately and with dignity, coupled with the fear of leakage and embarrassment in front of classmates, means some girls simply don’t attend school while menstruating. They risk falling behind their male counterparts, with potentially lasting effects on future education and career opportunities.

Women and girls who are forced to flee their homes due to conflict or natural disaster face similar struggles. Often temporary shelters and displacement camps lack private and safe facilities to bathe, use the restroom, or manage their menstrual hygiene. This leaves them vulnerable to harassment and gender-based violence.

Around the world, women are often expected to take responsibility for fetching water and cleaning house. In many cultures, women and girls are expected to collect the water and empty the latrines, and the task of collecting water keeps some girls out of school. In Kenya’s Turkana valley, Human Rights Watch spoke with girls who walk several kilometers each day to reach a dry riverbed where they dig for water to transport back to their school in 25-liter jerry cans. When water becomes scarce and sources dry up, women and girls are the ones who must adjust their routines and dedicate time to finding new sources, even if that means losing hours that could be spent in school or working.

Contaminated and unsafe water, even when abundant, often creates more chores for women and girls as they devote valuable time and energy to protect their families from illness. In Neskantaga, a First Nations community in Ontario, Canada that has been under a “boil water” advisory for two decades, a young mother described the hour-long process she undergoes daily to wash bottles in a way that reduces the risks of contamination for her 4-month-old infant with a rare heart condition.

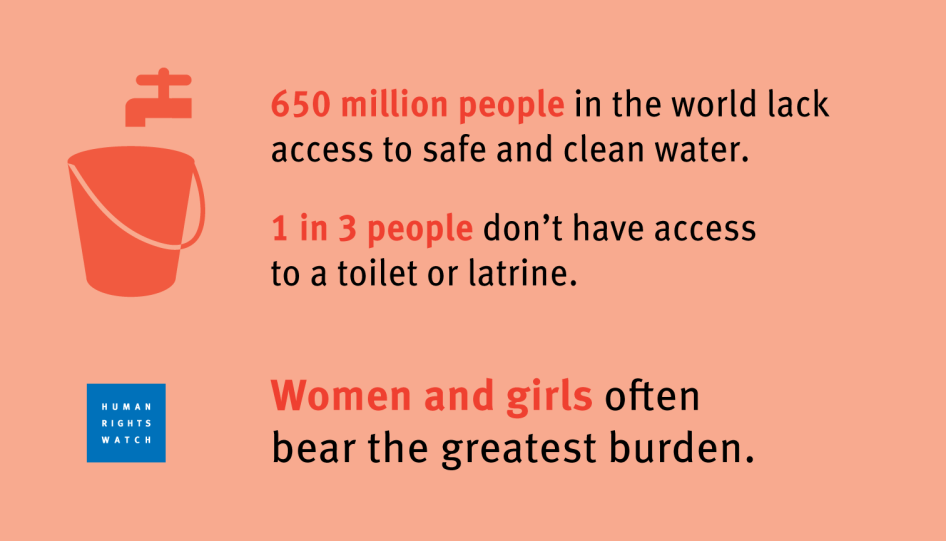

Similar situations play out millions of times a day around the world. Good hygiene practices such as washing hands regularly and bathing — including during menstruation — can stave off debilitating diseases and even save lives, but 650 million people in the world lack access to safe and clean water, and one in three people don’t have access to a toilet or latrine.

Everyone has a human right to water and to sanitation. As we strive toward gender equality on March 8, International Women’s Day, it’s crucial for governments not to ignore the particular ways in which pervasive difficulties getting access to water and sanitation affect women and girls. Gender equality can’t be achieved unless governments recognize and address these issues. So many women and girls are missing out on fulfilling their potential awaiting government action — or like Elisa, sitting on the toilet for hours because there is nothing else they can do.