The process is as universal as it gets: when a baby is born, a doctor, parent, or birth attendant announces the arrival of a “girl” or “boy.” That split-second assignment dictates multiple aspects of our lives. It is also something that most of us never question.

But some people’s gender evolves differently, and might not fit rigid traditional notions of female or male.

That should have no bearing on whether someone can enjoy fundamental rights. But for transgender people it does—to a humiliating, violent, and sometimes lethal degree.

As researchers on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights, we document countess cases of violence and discrimination against transgender people, whose very existence is outlawed in parts of the world. In Malaysia, state religious officials arrest trans people for the simple act of walking down the street wearing clothing deemed inappropriate to their assigned sex. Similar arrests have been made in Indonesia, Nigeria, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. Police have arrested trans people in Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia under laws that criminalize same-sex conduct.

Trans people are murdered at shockingly high rates, most notably in Latin America and the United States. Systematic marginalization contributes to high rates of suicide and HIV.

Despite this litany of rights violations, trans people have made tremendous strides in recent years toward achieving legal gender recognition—a crucial step toward curbing abuses.

The concept of a right to legal gender recognition—in other words, that everyone should be able to have documents marked with the gender with which they identify—has only recently gained traction. Many countries don’t allow people to change the gender designation on their documents at all. Others set stringent conditions for those who wish to do so.

Absent legal recognition in the gender with which they identify, every juncture of daily life when documents are requested or appearance is scrutinized becomes fraught with potential for violence and humiliation.

A trans woman in Malaysia told us that because she must present a male ID card at job interviews, the interviews inevitably dissolve into interrogations about her breasts. In Uganda, a trans man reported that a doctor threatened to call the police after realizing his appearance did not match his legal gender.

A trans man in Kazakhstan described his routine treatment by airport security: “First, the guard looks at my documents and is confused; next he looks at me and asks what’s going on; then I tell him I’m transgender; then I show him my medical certificates; then he gathers his colleagues around, everyone he can find, and they all look and point and laugh at me and then eventually let me go.”

Even in countries that consider themselves beacons on LGBT rights, including some European and Latin American countries and the US, transgender people are still forced to undergo demeaning procedures to change their documents, including gender reassignment surgery, forced sterilization, psychiatric evaluation, lengthy waiting periods, and divorce.

But some governments are beginning to realize they should no longer serve as gender gatekeepers.

Argentina broke ground in 2012 with a law that is considered the gold standard for legal gender recognition. Anyone over 18 can choose their legal gender and revise official documents without judicial or medical approval. Children can do so with the consent of their legal representatives or through summary proceedings before a judge.

In the next three years, Colombia, Denmark, Ireland, and Malta eliminated significant barriers to legal gender recognition.

In parts of South Asia, activists have fought for recognition of a third gender category. A Nepal’s Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that the government must recognize a third gender based on an individual’s “self-feeling.” Similar developments followed in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India.

Elsewhere, the very purpose of gender markers has been interrogated. New Zealand and Australia now offer the option of listing “unspecified” gender on official documents. The Dutch parliament has begun considering whether the government should record gender on identification documents at all.

In places where trans people’s very identities are criminalized, a future in which they may be legally recognized seems far off.

Yet it is precisely the persecution they face that lends urgency to the struggle for legal gender recognition. It highlights that states should not be in the business of regulating gender identities. Recognizing people’s self-identified gender does not require governments to acknowledge any new or special rights; instead, it is a commitment to the core idea that the state will not decide for people who they are.

To make this shift will require societies to recognize gender for what it is: a social construct.

Gender is deeply-felt by individuals; governments should not be in the businesss of adjudicating this identity through abusive protocols and bureaucratic snags. To alleviate this nightmare, governments should take some basic steps to separate legal and medical processes related to gender transition. That is to say, allow people to change their legal gender as an administrative process; and provide quality transition-related healthcare as a separate matter.

After making this procedural change, governments should adjust all relevant systems—including the multiple documents we carry in our daily lives, national databases such as the census, and any other gendered space ranging from restrooms to prisons. Dignity on paper must be ensured in practice as well.

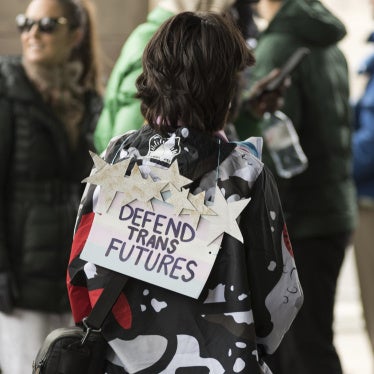

Transgender activists have made great strides in making this vision a reality in some parts of the word, but too often, their struggle has been a lonely one. Mainstream human rights organizations and donors should recognize that legal gender recognition is a fundamental human right, and should throw their weight, and their resources, into its realization.

Achieving the right to legal gender recognition is crucial to the ability of trans people to leave behind a life of marginalization and enjoy a life of dignity. A simple shift toward allowing people autonomy to determine how their gender is expressed and recorded is gaining momentum. It is long overdue.

Neela Ghoshal is a senior researcher and Kyle Knight a researcher in the LGBT rights program at Human Rights Watch.