(New York) – The government of Burma should take all necessary steps to protect communities at risk in Arakan State after violence between Buddhists and Muslims in western Burma left an unknown number dead. The government has taken inadequate steps to stop sectarian-violence between Arakan Buddhists and ethnic Rohingya Muslims, or to bring those responsible to justice.

Human Rights Watch urged the government to permit prompt access to international journalists, aid workers, and diplomats.

“Deadly violence in Arakan State is spiraling out of control under the government’s watch,” said Elaine Pearson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Opening the area to independent international observers would put all sides on notice that they were being closely watched.”

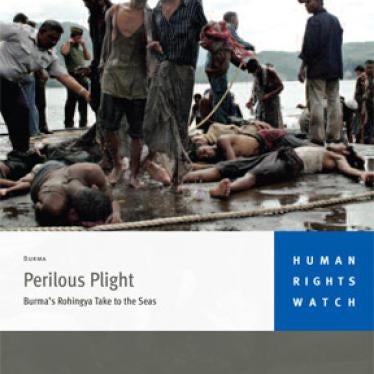

Brutal violence in Arakan State in western Burma erupted on June 3, 2012, when an estimated 300 Arakan Buddhists attacked a bus of traveling Muslims, killing 10 passengers. The angry mob was reacting to information that an Arakan girl was allegedly raped and murdered in late May by three Muslim suspects. At the time of the attack, the suspects were reportedly in police custody. Clashes have intensified since, with the police opening fire and allegedly killing Rohingyas, and Rohingya mobs burning Arakan homes and businesses. Mobs of Rohingya and Arakanese, armed with sticks and swords, have reportedly committed violence that resulted in a number of deaths. The violence has spread from Maungdaw to the state’s capital and largest town, Sittwe.

On June 7, the Burmese government announced an investigation into the violence. As clashes worsened, on June 10, President Thein Sein issued a state of emergency in the area, ceding complete authority to the Burmese army.

For decades, the Rohingya have routinely suffered abuses by the Burmese army, including extrajudicial killings, forced labor, land confiscation, and restricted freedom of movement. Arakan people have also faced human rights violations by the army. Using the army to restore order risks arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and torture, Human Rights Watch said.

“Given the Burmese army’s brutal record of abuses in Arakan State, putting the military in charge of law enforcement could make matters worse,” Pearson said. “The government needs to be protecting threatened communities, but without any international presence there, there’s a real fear that won’t happen.”

Where security permits, international agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees should maintain an on-the-ground presence in Arakan State to provide assistance and protection as possible.

For decades the Rohingya have borne the brunt of the earlier military government’s brutal state-building policies. The Rohingya have been formally denied citizenship and were excluded from the last census in 1983. They are widely regarded within Burma as “Bengalis” – people of Bangladesh nationality. Since the 1960s there have been multiple campaigns led by the Burmese authorities to expel the Rohingya from Burma, resulting in a litany of human rights violations. There are an estimated 800,000 Rohingya in Burma, and about 200,000 live in Bangladesh, of which 30,000 live in squalid refugee camps.

“The Burmese government’s policies of exclusion have fostered resentment against the Rohingya,” said Pearson. “Longer-term, the government should be thinking about how to address the years of discrimination and neglect that the Rohingya have faced, provide some mechanism for accountability, and ensure the rights of Rohingya equally with other Burmese.”

The ongoing violence in Arakan State shows that despite the democratic progress of recent months, there are still formidable challenges for human rights in Burma, Human Rights Watch said. Many areas populated by ethnic minorities have seen few benefits from the reform process. International journalists and aid workers still face restricted access to large parts of the country.

Influential governments such as the US, Japan, Australia, and members of the European Union should continue to press for full civilian control over the military and building the rule of law, instead of giving up all its leverage at a moment when the reform process has barely begun.