(New York) – Documents recently discovered by Human Rights Watch in Tripoli reveal new details of the high level of cooperation among United States, United Kingdom, and Libyan intelligence agencies in the transfer of terrorism suspects, Human Rights Watch said today. The documents underscore the need for the US and UK to account for past abuses, Human Rights Watch said.

The documents, discovered on September 3, 2011, describe US offers to transfer, or render, at least four detainees from US to Libyan custody, one with the active participation of the UK; US requests for detention and interrogation of other suspects; UK requests for information about terrorism suspects; and the sharing of information about Libyans living in the UK. This cooperation took place despite Libya’s extensive and widely known record of torture and other ill-treatment of detainees.

“The Tripoli documents show that the US sought promises of humane treatment from a government well known to practice torture,” said Peter Bouckaert, Emergencies director at Human Rights Watch. “Given Muammar Gaddafi’s record of torture and abuse, it would have been absurd for the US intelligence agencies to believe any assurances from his regime.”

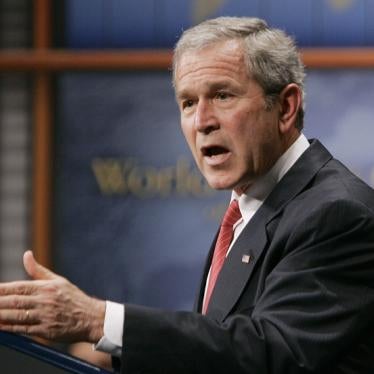

The US rendition documents, drafted during the administration of President George W. Bush, show that the US sought so-called “diplomatic assurances” that detainees would be “treated humanely” following their transfer to Libya. The UK documents, drafted under the previous Labour government, show that the UK government took credit for involvement in one rendition, sent information about Libyans in the UK, and requested information from Libyan intelligence.

Research by Human Rights Watch, as well as the US State Department’s own documentation at the time, demonstrated a clear record of torture and other ill-treatment by Libyan detention authorities. Nevertheless, the UK entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Libya in October 2005, with Tripoli promising not to torture terrorism suspects sent from the UK. British courts in 2007 blocked returns of people to Libya under the MOU on the grounds that the suspects were at real risk of being tortured if they were sent back to Libya.

US, UK Policy and Practice

The Bush administration transferred more than 100 detainees to various countries from 2004 to 2006, including at least seven to Libya, for interrogation and subsequent detention. The US government was responsible for these people being held incommunicado and did not provide information on their fate or whereabouts, in violation of the international legal prohibition against enforced disappearances. The US is not known to have sent any detainees to Libya since 2007, and the administration of President Barack Obama has not reported any renditions to any country since taking office.

The Obama administration, however, has not precluded rendering detainees to countries where there is a substantial danger of torture. In such cases, the administration has said it would continue to take into account a country’s assurances that it will treat a detainee humanely after rendition by the US or transfer to a home country or third country upon release from US detention.

In the UK, despite adverse court rulings in the European Court of Human Rights and some British courts, the current coalition government has continued the use of diplomatic assurances, referred to as “deportation with assurances.”

“The US and UK need to renounce sending people to governments that practice torture,” Bouckaert said. “The experience of Libya ought to teach the US and UK what common sense should have told them from the start – that whatever cynical promises you may get, if you deliver prisoners to torturers, they will be tortured, and eventually the world will know it.”

Obligations and Accountability

Under the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the “Convention against Torture”), which the US ratified in 1994 and the UK in 1988, no one is to be sent to a country where there are substantial grounds for believing that they might be tortured or mistreated. This obligation has been interpreted to require governments to provide a mechanism for people to challenge decisions to transfer them to another country.

The Convention against Torture also obligates countries to investigate credible allegations of torture and other ill-treatment, including complicity. However, despite overwhelming evidence of US government involvement at senior levels in the use of torture, and of US and UK complicity in torture in third countries, neither government has conducted sufficient investigations into the alleged conduct.

In the US, Attorney General Eric Holder appointed Assistant US Attorney John Durham to investigate detainee abuse but limited the investigation to “unauthorized” acts by US interrogators. Ultimately the Durham inquiry recommended that the Obama administration should pursue further criminal investigations in the abuse of only two detainees who died in US custody. The administration has ignored calls for investigations into the alleged torture and mistreatment of hundreds of other detainees while in US custody or rendered to third countries for abuse.

In the UK, the coalition government agreed in June 2010, given the evidence that had emerged of UK complicity in torture in Pakistan and elsewhere, to establish the “Detainee Inquiry” to examine UK involvement in rendition and complicity in overseas torture. The decision followed extensive advocacy efforts by Human Rights Watch and other organizations. The inquiry will begin after the completion of two related police investigations into alleged criminal conduct by British officials overseas. But the government forced the inquiry, in July 2011, to accept rules on disclosure and witness participation that deprive it of transparency. As a result, Human Rights Watch, along with other organizations and lawyers acting on behalf of detainees, withdrew their cooperation.

Prime Minister David Cameron told Parliament on September 5 that the Detainee Inquiry will also look at the fresh revelations about possible UK involvement in renditions to Libya and Gaddafi-era abuses. While an examination of the Libya allegations is crucial, the Detainee Inquiry’s defects make an effective investigation highly unlikely, unless the government changes the Inquiry's protocol. An effective inquiry would require openness, with the final decision on publishing evidence made by an independent judge, and not the government itself.

“If the British government is serious about getting to the bottom of UK involvement in abuses against terrorism suspects, it needs to fix the Detainee Inquiry as a matter of urgency,” Bouckaert said.

Document Details

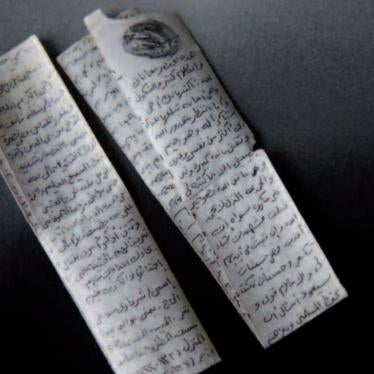

The documents discovered by Human Rights Watch in Tripoli include communications between the former Libyan intelligence chief, Musa Kusa, and the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service (commonly known as MI6), and German and other government intelligence agencies. Human Rights Watch discovered the documents while examining the Libyan government’s external security building in Tripoli, which had been abandoned by Gaddafi forces. The files in the archives contain, among other things, evidence of crimes committed during Gaddafi’s 42 years in power. Human Rights Watch only viewed several hundred of what appeared to be tens of thousands of documents in the building, photographing approximately 300 and leaving the originals in place.

Some of the documents contain information about CIA renditions of members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, which had sought since the 1990s to overthrow the Gaddafi government and played a key role in the current revolt in Libya.

One of the group’s members was Abdul Hakim Belhaj, now the rebel military commander in Tripoli. The documents, which refer to Belhaj by his pseudonym Abu Abdullah al-Sadiq, detail an offer by the CIA on March 6, 2004, to “rend[er]” Belhaj from Malaysia, where he had been detained, to Libya. In the memo, the CIA asked the Libyan government to ensure that Belhaj would be “treated humanely” and that the CIA would have access to him for questioning once he was in Libyan custody. The CIA transferred Belhaj to Libya around March 9, 2004.

Another document is a letter from a senior MI6 official to Musa Kusa congratulating him on the “safe arrival of Abu ‘Abd Allah Sadiq” and taking credit for Britain’s role in the rendition, which “was the least we could do for you and Libya.”

During a research mission to Libya in April 2009, Human Rights Watch interviewed Belhaj, who had been imprisoned by Libyan authorities in the notorious Abu Salim prison where 1,200 prisoners were massacred in 1996. He told Human Rights Watch that CIA agents had apprehended him and his wife, who he said was then six months pregnant, in Malaysia around March 3, 2004, and transferred him to Libya. Belhaj alleged that while he was detained by the CIA, agents questioned him about his alleged ties to al Qaeda – which he denied – and, among other things, stripped him naked, beat him, and hung him against a wall by one arm and then by one leg.

The public record makes clear that the US and UK governments were aware of the pervasive use of torture by Libyan authorities at the time they rendered detainees to the country. The US State Department’s 2004 Human Rights Country Report on Libya stated that:

Security personnel reportedly routinely tortured prisoners during interrogations or as punishment. Government agents reportedly detained and tortured foreign workers, particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa. Reports of torture were difficult to corroborate because many prisoners were held incommunicado.

Some of the reported methods of torture, according to the report, included: chaining prisoners to a wall for hours; clubbing; applying electric shock; applying corkscrews to the back; pouring lemon juice in open wounds; breaking fingers and allowing the joints to heal without medical care; suffocating with plastic bags; deprivation of food and water; hanging by the wrists; suspension from a pole inserted between the knees and elbows; cigarette burns; threats of being attacked by dogs; and beating on the soles of the feet.

The Tripoli documents also contain information about CIA renditions and cooperation with the Libyan government in detention in at least five other cases, with specific information including flight schedules and detailed questions that the CIA wanted the Libyans to ask the detainees. They also confirm that the CIA sent agents to interrogate some suspects in Libya after the US had transferred them to Libya.

One letter from the CIA states: “We are also eager to work with you in the questioning of the terrorist we recently rendered to your country.… I would like to send to Libya an additional two officers, and I would appreciate if they could have direct access to question this individual.”

Many of the documents Human Rights Watch examined were drafted during a period of political rapprochement between the US and UK and Libya, after Libya had agreed to end its nuclear weapons program and cooperate on intelligence matters.

Human Rights Watch could not confirm the authenticity of the documents, but they appear to corroborate previously known information about the CIA rendition program.

The CIA secret detention program was authorized under a classified September 17, 2001 presidential directive and remained in place until it was terminated by the Obama administration. Although it is not known exactly how many people the US transferred to other countries as part of its rendition program, investigations by the media and human rights groups and the declassification of certain documents have uncovered more than 100 cases.