12-year-old Mia came to the rape treatment center in Santa Barbara because her school counselor suspected sexual abuse. At the rape center, she consented to a long and invasive exam, during which a nurse collected forensic and DNA evidence that could be linked to the perpetrator. Like most victims, Mia (a pseudonym) was told that this evidence, known as a "rape kit," would be used to try to identify her assailant through a DNA match.

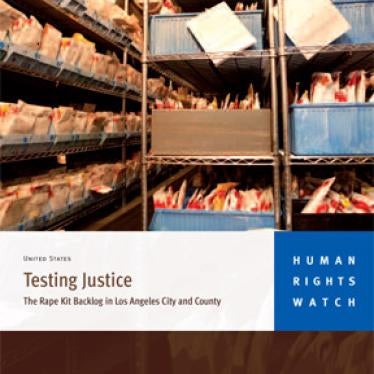

But the rape kit collected from Mia's body was one of tens of thousands of such kits across the United States that sit in storage, untested, for years.

The police officers who questioned Mia closed the case because she gave confused and vague answers when they questioned her. But she gave these answers since she was interviewed with her stepfather in the room. After three years of continuing abuse, she mustered the courage to reveal that it was her stepfather who had been raping her all along. The DNA evidence from a new rape kit and the old one led to his conviction.

"It is shocking that police and prosecutors make decisions about whether to take a rape case forward before they see what the kits have to say," said Sarah Tofte, the Human Rights Watch researcher who investigated the rape kit testing backlog. "We are asking so much of someone immediately after a traumatic experience, and too often, for nothing."

If the police had a policy in place requiring the testing of every collected rape kit, they would have discovered semen in Mia's rape kit. In a good police investigation, they should have collected reference samples from potential male suspects, including her stepfather. If this had been the case, Mia would have been spared three more years of repeated rape.

Tofte decided to focus her investigation of rape kit backlog on Los Angeles County, where she heard from staff members of a rape treatment center that it was particularly severe. The first challenge was to get law enforcement officials to acknowledge the problem, Tofte said. "They said it would take too much time and effort even to count the kits."

Human Rights Watch collected evidence that showed that failing to test rape kits has serious implications for public safety. For example, when New York decided to test every rape kit in its possession during the 1990s, the rate of arrests resulting from reported rape cases rose from around 30 percent to 70 percent.

Tofte asked members of Human Rights Watch's California Committee South to put her in touch with local lawmakers and city and county officials. She informed journalists and editors about the issue, which led to considerable coverage in local and national media, including stories and op-eds in the Los Angeles Times.

Then, in October 2008, the Los Angeles Sheriff's Office yielded to the pressure and began to count the untested rape kits in its possession. It found a backlog of 5,000. By early 2009, the Los Angeles Police Department followed suit, finding 5,000 more kits stowed away. An additional 2,500 untested kits were later found in other cities in Los Angeles County. Tofte found that, while the city and the county had received $8 million in federal funding for DNA testing in rape cases, much of the money had not been spent.

Human Rights Watch published Tofte's findings in a report in March 2009, which led to another wave of publicity, including a column in the New York Times by Nicholas Kristof.

On May 18, the public pressure that Human Rights Watch generated led to a landmark vote by the Los Angeles City Council. Recognizing the immensity of the problem, the council pledged new funding to expedite the testing of all the rape kits under the jurisdiction of the Los Angeles Police Department. The department vowed to eliminate the backlog permanently within two years.

From now on, evidence collected in rape kits in Los Angeles will be tested and used to identify, find, and try people who have committed rape. Assailants who already have criminal records will be matched during DNA searches and prevented from striking again. More matches to more offenders may be made, which could lead to more arrests.

Human Rights Watch and its allies in California will continue to exert pressure to ensure the rape kit backlog is permanently eliminated. Without Tofte's perseverance, thousands of rape kits in Los Angeles County would still be in storage. Now, the injustice done to thousands of rape victims is being remedied, kit by kit.