This Wednesday, unless the UK foreign secretary takes rapid action, Britain’s High Court will hold a hearing to assess whether the UK government should be ordered to hand over secret documents to lawyers for a Guantanamo detainee. The detainee in question, Binyam Mohamed, faces possible charges of conspiracy and material support for terrorism before a military commission at Guantanamo.

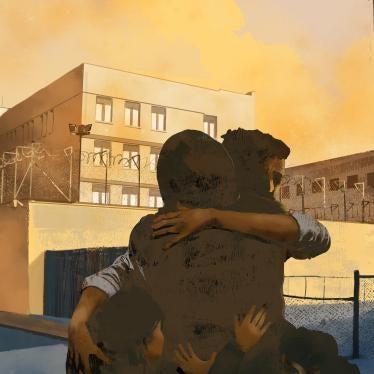

Mohamed, an Ethiopian national and former UK resident, was arrested in Pakistan in April 2002. Transferred to US custody, he was reportedly rendered by the CIA to Morocco, detained there secretly for over a year, and then moved for several months to a secret CIA detention site in Afghanistan. He then spent a few months in military detention at Bagram air base in Afghanistan, and was ultimately brought to Guantanamo Bay in September 2004.

Mohamed claims that he was brutally tortured during his time in secret detention, and that the evidence that will likely be used to prosecute him is a result of that torture. He also claims that the UK government has information that supports his claims of abuse.

Last week, in an important judgment, the UK High Court ruled in Mohamed’s favor. It found that the British government was under a legal obligation to disclose to Mohamed’s counsel the information it possesses relating to Mohamed’s whereabouts, treatment, and interrogation between April 2002 and May 2004. The court emphasized that this information is “not merely necessary but essential” to Mohamed’s defense against military commission charges.

While the court stopped short of ordering the foreign secretary to hand over the information – allowing additional time for the national security implications of disclosure to be considered – it will reach the mandatory disclosure question at its hearing this week.

From Britain to Pakistan to the Prison of Darkness

Binyam Mohamed came to Britain in 1994, when he was a student, after having spend a short period in the United States. He converted to Islam while in the UK, and in mid-2001 he left the UK for Pakistan and Afghanistan. He claims that he traveled to the region because he wanted to kick a drug habit.

The military commission charges that have been sworn against Mohamed allege that he attended an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, and later received training in building remote-controlled explosive detention devices in Pakistan. While living at an Al Qaeda safe house in Lahore, Pakistan, the charges say, Mohamed allegedly agreed to be sent to the United States to conduct terror operations.

Mohamed was arrested at the Karachi airport on April 10, 2002, as he attempted to leave Pakistan to fly to London. Although he was initially detained in Karachi, he claims that he was interrogated there by US agents. The UK High Court has also confirmed that a British agent visited Mohamed in Pakistani custody on May 17, 2002.

Mohamed claims that he was rendered by the CIA to Morocco in July 2002. There, he claims, he was beaten, repeatedly cut on his genitals, and threatened with rape, electrocution and death. Interrogators reportedly asked him detailed questions about his seven years in London, based on information that his lawyers believe came from British sources.

In late January 2004, Mohamed says, he was sent to Afghanistan, where he was held in a secret CIA prison – called the “Prison of Darkness” – until May 2004. At that point, he was transferred to military detention, first at Bagram air base in Afghanistan, then at Guantanamo, where he remains.

According to the UK High Court, the military commissions case against Mohamed is based on confessions Mohamed made while in military custody – after May 2004 – not on anything he said while being interrogated by the CIA. Mohamed claims, however, that it was the abuse in CIA custody that induced him to confess while in military custody, and so proof of those CIA abuses are crucial to his defense.

Refusal to Disclose

As part of a continuing effort to cover up the CIA’s misdeeds, US officials have refused to provide Mohamed or his lawyers any information whatsoever about his treatment or whereabouts from the time of arrest in April 2002 until he was transferred to Bagram in May 2004. To date, the UK government has similarly refused to provide Mohamed’s lawyers any such information, although it has acknowledged that some documents in its possession might be exculpatory.

In last week’s ruling, the High Court noted that the UK foreign secretary had acknowledged that Mr. Mohamed had established an arguable case that he had been subject to illegal rendition and torture. The court also found that the British security forces had facilitated Mohamed’s interrogations by supplying information and questions to US officials, even while they knew that Mohamed was being held incommunicado in a non-military detention facility overseas.

The court found, in short, that the relationship of the UK government to the US authorities with regard to Mohamed “was far beyond that of a bystander or witness to the alleged wrongdoing.” Because the UK was in some way a participant, not simply an observer, the court held that the UK is legally obligated to provide Mohamed with information relating to his abuse.

Not only did the court deem this information to be “essential” to Mohamed’s ability to adequately defend himself, it emphasized the need for the government to provide the necessary information as soon as is practically possible. The reason for the hurried timing lies in the military commissions’ timetable. At present, military commission charges against Mohamed have been prepared, but the commission’s convening authority has not yet signed off on them. In order to potentially affect the charging decision, Mohamed has an important interest in getting exculpatory information to the convening authority before that decision is made.

The Prospect of Mandatory Disclosure

The UK court decried the fact that the US authorities have failed to provide this potentially exculpatory information to Mohamed’s counsel, particularly since both his counsel are security-cleared. But it recognized, as well, that the United States’ failure is no excuse for Britain’s inaction.

Unless the UK foreign secretary voluntarily provides the relevant documents to Mohamed’s counsel before Wednesday, the High Court will consider ordering disclosure. Such an order, which the court seems presently inclined to grant, would open an important crack in the wall of secrecy that surrounds the CIA’s rendition, detention, and interrogation abuses.