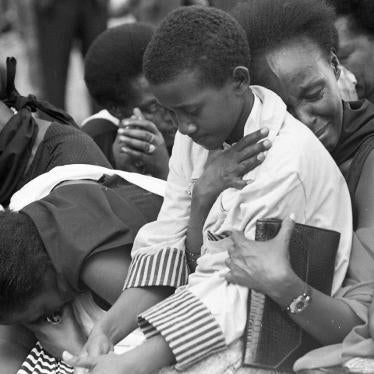

The Rwandan genocide could have been stopped with tougher action from outside powers, according to a comprehensive study released today by Human Rights Watch and the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues. Next week will mark the fifth anniversary of the genocide, in which more than half a million Tutsi and thousands of Hutu associated with them were killed.

An internationally-recognized team of historians, political scientists, and lawyers spent four years conducting research and analysis of the genocide. The team was the first to have access to documents of the genocidal government, as well as to previously unpublished diplomatic and judicial records. Researchers also conducted hundreds of interviews with Rwandans—both local organizers of the genocide and those they targeted for extermination. The 800 page history contains dozens of maps and primary sources.

"The world has been saying for five years now that the Rwandan genocide was a terrible thing," said Alison Des Forges, author of the study. "But that's not enough. We need to know how such killing campaigns work, if we hope ever to prevent them."

Many people outside Rwanda called the genocide a spontaneous outburst of ethnic violence on a massive scale. But this study makes clear how a relatively small group of determined killers planned the mass murder for months in advance and then enticed and intimidated others into following them. Other observers blamed the "failed state." But this history shows how organizers took over a highly centralized government and used its efficient machinery to carry the killing campaign into every part of the country. The study recounts security meetings in which specific people were chosen for slaughter, the disposal of bodies was arranged, and the property of victims was divided.

"Our extraordinarily rich sources, both written and spoken, bring alive both the suffering of the victims and the motives of the killers," said Des Forges, a consultant for Human Rights Watch and a historian specializing in the study of central Africa.

The research team also interviewed foreign decision-makers and had access to confidential diplomatic accounts. It establishes that U.S., French, and Belgian authorities, as well as those at the United Nations, received dozens of warnings in the months before the genocide but failed to act effectively. Even worse, foreign leaders reacted timidly and tardily once the killing began.

"The Americans were interested in saving money, the Belgians were interested in saving face, and the French were interested in saving their ally, the genocidal government," said Des Forges. "All of that took priority over saving lives."

Unwilling to call genocide by its name, foreign leaders treated the outlaw government as legitimate and even allowed it to remain a member of the U.N. Security Council. The killers used their "legitimacy" abroad to buttress their authority at home and sought to cover the genocide with a cloak of legality. In a similar way, officials and ordinary people used the pretext of "orders" from a supposedly legitimate government to hide from themselves and others the evil they were doing.

The study shows that even people at local meetings, in areas far from the capital, discussed foreign reactions to the genocide. Protests from abroad, as hesitant and conditional as they were, did produce changes in tactics. "If such small efforts could get results, imagine what a firmer stand, taken earlier, might have produced," said Des Forges. "International interventions must be prompt, strong, and smart. We hope this history will make us all smarter about how genocide works—and how to disrupt it more effectively."