North Korea in 2020 remained one of the most repressive countries in the world. Under the rule of Kim Jong Un, the third leader of the nearly 75-year Kim dynasty, the totalitarian government deepened repression and maintained fearful obedience using threats of execution, imprisonment, enforced disappearance, and forced labor. Due to the border closures and travel restrictions put in place to stop the spread of Covid-19, the country became more isolated than ever, with authorities intensifying already tight restrictions on communication with the outside world.

The government continued to sharply curtail all basic liberties, including freedom of expression, religion and conscience, assembly, and association, and ban political opposition, independent media, civil society, and trade unions.

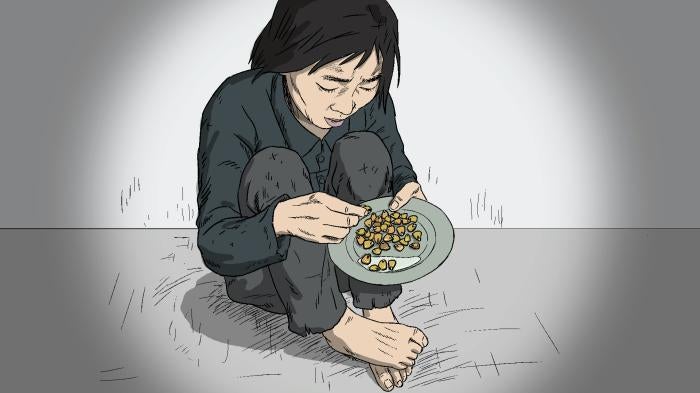

Authorities in North Korea routinely send perceived opponents of the government to secretive prison camps where they face torture, starvation rations, and forced labor. Fear of collective punishment is used to silence dissent. The government systematically extracts forced, unpaid labor from its citizens to build infrastructure and public works projects. The government also fails to protect the rights of children and marginalized groups including women and people with disabilities.

North Korea’s failures to promote economic rights resulted in increased harms to the population in 2020. On January 1, at a major party meeting, Kim Jong Un stated that North Koreas would need to “tighten our belts” and find ways to become self-reliant. However, the government continued its prioritization of strategic weapons development, leading the UN Security Council to maintain severe economic sanctions.

The economic impact of those sanctions, which was intensified by the Covid-19 lockdown—as well as severe floods that hit the country between June and September and destroyed crops, roads, and bridges—undermined the country’s agricultural production plan. The government continued to rebuff international diplomatic engagement and repeatedly rejected offers for international aid.

Freedom of Movement and Information

Moving from one province to another or abroad without prior approval remains illegal in North Korea. North Korea continued jamming Chinese mobile phone services at the border and arresting persons caught communicating with people outside the country, a violation of the right to information and free expression.

Networks that facilitate North Koreans’ escape to safe third countries reported extreme difficulties due to Covid-19 health measures and checkpoints on top of surveillance and other existing obstacles to movement in countries through which people transit. Many North Koreans in China reportedly had to stay hidden in safe houses for months, with the Chinese government continuing to catch North Korean refugees and trying to return them, violating China’s obligation to protect them under the Refugee Convention.

Despite the Covid-19 health measures, the Chinese government reportedly forcibly returned North Koreans until March. South Korean media with contacts in North Korea reported instances of the North Korean government rejecting Chinese proposals to return North Korean refugees in February and October.

The Ministry of Social Security considers defection to be a crime of “treachery against the nation.” North Koreans fleeing to China are protected under international law as refugees sur place, since those forcibly returned by China face violations that a 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) on human rights in North Korea has condemned as crimes against humanity. While several thousand people escaped North Korea annually earlier this decade, the numbers have decreased in recent years. Just over one thousand North Koreans fled to the south in 2019, but only 195 did so between January and September of 2020.

Forced Labor

The North Korean government routinely and systematically requires forced, uncompensated labor from most of its population—including women and children through the Women’s Union or schools; workers at state-owned enterprises or deployed abroad; detainees in hard labor detention centers (rodong dallyeondae); and prisoners at ordinary prison camps (kyohwaso) and political prison camps (kwanliso)—to control its people and sustain its economy. A significant number of North Koreans must perform unpaid labor, often called “portrayals of loyalty,” at some point in their lives.

The government routinely compels many North Koreans, who are not free to choose their own job, to join paramilitary labor brigades (dolgyeokdae) that the ruling party controls and operates, working primarily on buildings and infrastructure projects. In theory, they are entitled to a salary, but in many cases, the dolyeokdae do not compensate them.

North Korea remained in 2020 one of only seven UN member states that has not joined the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Pretrial Detention, Due Process Violations, and Torture

The North Korean government’s pretrial detention and criminal investigation system remained arbitrary, violent, cruel, and degrading. Ordinary citizens have no access to North Korea’s laws, which are vaguely worded and lack definitions. Law enforcement agencies and courts are controlled by the Workers’ Party of Korea, and connections and money are important determinants of whether one is detained or receives better treatment or shorter sentences. People in pretrial detention are subjected to beatings, torture, dangerous and unhygienic conditions, and other mistreatment in interrogation facilities (kuryujang), with women and girls particularly targeted for sexual violence.

Marginalized Groups

The North Korean government uses songbun, a socio-economic political classification system created at the country’s founding that groups people into varying classes including “loyal,” “wavering,” or “hostile,” discriminating against lower classed persons in areas including employment, residence, and schooling. Pervasive corruption allows some maneuvering around the strictures of the songbun system, with government officials accepting bribes to allow exceptions to songbun rules, expedite or provide permissions, provide access to certain market activities, or avoid possible punishments.

Women and girls in North Korea suffer widespread gender discrimination, high levels of sexual violence and harassment, and constant exposure to government-endorsed stereotyped gender roles, in addition to the abuses suffered by the population in general.

Human traffickers and brokers, often linked to government officials, subject women to forced labor, sexual exploitation, and sexual slavery in China, including through forced marriage. On July 28, 2020, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) published a report that said women forcibly repatriated from China to North Korea were imprisoned without due process or a fair trial and then subjected to egregious human rights abuses. While in detention, the women experienced food deprivation, sexual violence, infanticide, and forced labor and were held in overcrowded prisons with dangerous conditions.

Covid-19

In 2020, the North Korean government imposed various restrictions in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. While some measures that limited rights were justified by public health exigencies, others were not necessary or not proportionate and permitted grave abuses under the pretext of protecting against the spread of Covid-19.

For instance, the government intensified enforcement of a ban on “illegal” travel to China, including by executing persons caught while attempting to escape. In August, the government created buffer zones one to two kilometers from the northern border, with guards ordered to “unconditionally shoot” on sight anyone entering without permission. Also under the pretext of Covid-19 prevention, on September 22, the North Korean navy shot and killed a 47-year-old South Korean fisheries official on a boat near North Korea’s western sea border.

The government also implemented drastic quarantines for anybody arriving from overseas at border cities, ports, and airports. North Koreans reentering the country through northern border cities did not have the option to quarantine at home and reportedly were quarantined in government-designated facilities with little food (three meals a day consisting of a bowl of boiled rice and crushed corn and some soup), inadequate medical treatment, and lack of basic needs products like electricity, some for up to 40 or 50 days.

North Korea maintains there are no Covid-19 cases in the country, but South Korean media with sources inside North Korea reported several deaths featuring coronavirus-like symptoms. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of October 29, North Korea had tested 12,072 people for Covid-19, with all resulting “negative” for the virus, and as of August 20, a total of 30,965 people had been placed under quarantine and as of October 29, 32,182 released.

The government also strengthened restrictions on travel domestically, issuing fewer official travel permits, imposing new temporary road checkpoints, and enhancing enforcement to prevent “illegal” travel. These measures, though justified on public health grounds, severely reduced people’s ability to access food, medicine, and other basic goods. Schools delayed their scheduled start from March until June.

On June 9, Tomás Ojea-Quintana, special rapporteur on human rights in North Korea, recommended that the North Korean government seek more international assistance to prevent the spread of the virus, and make all public health data publicly available, allow citizens free access to electronic communication and global news, and permit international humanitarian organizations access to the country. The government did not respond.

Key International Actors

North Korea has ratified five human rights treaties, but it has ignored its obligations under all of them. A 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry on human rights in North Korea found that the government committed gross, systematic, and widespread rights abuses, including extermination, murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, rape, forced abortions, and other sexual violence. It recommended the UN Security Council refer the situation to the International Criminal Court (ICC). The North Korean government has repeatedly denied the commission’s findings and refused to cooperate with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Seoul or the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in North Korea.

On June 22, 2020, the UN Human Rights Council adopted without a vote a resolution emphasizing the advancement of accountability efforts and mechanisms. As recommended by the Commission of Inquiry and mandated by subsequent council resolutions, the UN high commissioner for human rights continued to gather evidence of human rights abuses and crimes against humanity committed by the government. In November 2020, the UN General Assembly’s third committee passed without a vote a resolution condemning human rights in North Korea.

Although the US-led efforts to place North Korea’s human rights violations on the UN Security Council agenda as a threat to international peace and security between 2014 and 2017, since 2018 its mission to the UN failed to do so, and there was no formal council discussion of North Korea’s record in 2020. However, the US government continued to impose human rights-related sanctions on North Korean government entities, as well as on Kim Jong Un and on several other top officials. The US also continued to fund organizations promoting human rights in North Korea.

Despite North Korea’s rejection of any diplomatic engagement, South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s administration attempted to develop better relations with Pyongyang in 2020, apparently to placate North Korea. The South Korean government has not adopted a clear policy on North Korean human rights issues and in 2020 it did not co-sponsor key resolutions on North Korea’s human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly.

On 6 July, the UK introduced new human rights sanctions, including against two North Korean entities in charge of the forced labor, torture, and murder that takes place in the country’s political prison camps (kwanliso) and ordinary prison camps (kyohwaso).