March 2021

Introduction

This submission highlights Human Rights Watch’s key concerns regarding the Tajik government’s compliance with its international obligations since its last Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in 2016. In 2016, Tajikistan’s UPR took place amid a government’s massive crackdown against members and supporters of a banned opposition party. Since then, the country’s human rights record worsened, with the authorities continuing to harass critics and dissidents both inside and outside the country, as well as their families. Over the reporting period of five years the Tajik government has harassed and imprisoned lawyers and journalists, who endured an estimated 80 attacks in the period between 2017 and 2019. The government continued blocking independent media and social media sites, as well as limiting citizens’ freedom of religion and belief via the onerous laws against “organizing activities of extremist organizations” and “religious discord”. Domestic violence continued to be a serious problem, as women and girls who experience abuse lack adequate protection and support and are unable to seek justice against the perpetrators due to inadequate legislation.

HARASSMENT OF CRITICS AND DISSIDENTS

Despite supporting recommendations in the previous UPR cycle to “respect freedom of expression, assembly and association, in particular by not prosecuting people on the sole grounds of their membership of a political movement” (118.44) and several others, Tajikistan has continued harassing and imprisoning government’s critics, opposition, foreign-based dissidents and their family members within the country.

Since mid-September 2015, following the forced closure of Tajikistan’s leading opposition party, the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), authorities have subjected party members and their relatives to arbitrary detention and imprisonment, in addition to persons associated with the opposition movement Group 24 and other critical groups. In June 2016, just a few weeks after the conclusion of its UPR, Tajikistan’s Supreme Court sentenced IRPT’s first deputy and deputy chairmen, Saidumar Husaini and Mahmadali Hayit, to life in prison, other party leaders to 28 years in prison following a closed trial marked by serious due process violations. In December 2016, prison officials tortured imprisoned IRPT activist Rahmatulloi Rajab in retaliation for the journalistic work of his son Shukhrati Rahmatullo.

Authorities regularly harass relatives of critics living abroad.

In September 2018, a Dushanbe court sentenced Rajabali Komilov, the brother of Germany-based IRPT member Janatullo Komilov, to ten years in prison for alleged party membership and unspecified crimes allegedly committed during Tajikistan’s 1992-1997 civil war. Komilov told Human Rights Watch that the case against his brother was brought to coerce his return to the country.

In June 2019, Europe-based journalist Humayra Bakhtiyar told Human Rights Watch that authorities were harassing her family in Dushanbe to pressure her to return to Tajikistan. She told Human Rights Watch that police also called her 57-year-old father, Bakhtiyar Muminov, to come for a talk on June 12, her birthday, despite her father having suffered a heart attack that required surgery in April. Police forced Muminov to call Bakhtiyar and try to convince his daughter to return, forcing her father to repeat their questions into the phone. Later they threatened to arrest Muminov.

In March 2020, Austrian authorities extradited Hizbullo Shovalizoda to Tajikistan after denying him asylum. Shovalizoda was arrested upon arrival in Dushanbe and accused of being an IRPT member and participating in an attempt to overthrow the government. The party reported that Shovalizoda had never been a member. In June 2020 he was sentenced to 20 years in prison on vague charges of “organizing activity of an extremist organization” and “treason.”

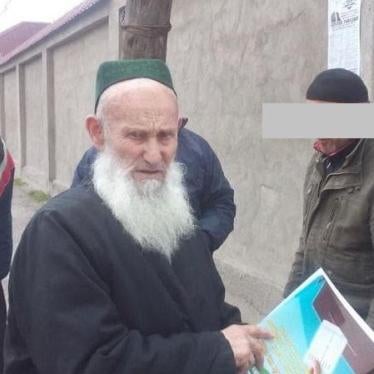

In December 2020, the Tajik authorities sentenced an 80-year old man, Doniyor Nabiev, to seven years in prison for materially helping families of political prisoners. He was charged with and found guilty of “organizing activity of extremist organization” on grounds of his previous membership in the banned IRPT.

The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called in May 2018 for the release of IRPT deputy chairman Mahmadali Hayit, in June 2019 for the release of lawyer Buzurgmehr Yorov, and in January 2020 for the release of 11 senior IRPT members (Saidumar Husaini, Muhammadali Faiz-Muhammad, Rahmatulloi Rajab, Zubaidulloi Roziq, Vohidkhon Kosidinov, Kiyomiddin Avazov, Abduqahar Davlatov, Hikmatulloh Sayfulloza, Sadidin Rustamov, Sharif Nabiev and Abdusamat Ghayratov). In July 2018, the Human Rights Committee declared the continued imprisonment of opposition figure, Zayd Saidov, a violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and urged his immediate release.

Tajikistan should:

- Uphold the freedoms of expression, association, and assembly; implement the opinions of the Human Rights Committee and the WG on Arbitrary Detention on cases mentioned above; release Hizbullo Shovalizoda, Rajabali Komilov, and all other persons imprisoned on politically motivated charges.

- Stop harassing the family members of Tajik citizens living abroad and end the misuse of extradition mechanisms to return Tajik citizens to Tajkistan to face politically motivated harassment and persecution;

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

The Tajik government previously accepted recommendations to guarantee freedom of expression and media, and to “ensure that journalists and other individuals be able to freely exercise the right freedom of expression and have access to Internet without undue restrictions” (118.52), and “that journalists and human rights defenders can do their work independently and without fear of reprisals from the authorities, be they of financial, legal or of another nature” (118.65). However, the Tajik authorities have failed to act on these recommendations. Under the pretext of protecting national security, Tajikistan’s state telecommunications agency regularly blocks websites that carry information potentially critical of the government, including Facebook, Radio Ozodi, the website of Radio Free Europe’s Tajik service, and opposition websites. Since 2016, the authorities have forced closure of several independent media outlets, such as TojNews or Nigoh, one of Tajikistan’s last independent newspapers after it had ostensibly insulted president Rahmon by misspelling the word “president.”

In July 2017, the Tajik parliament passed amendments allowing security services to monitor individuals’ online activities, including by keeping records of mobile messages and social media comments. Citizens who visit “undesirable” websites are subject to surveillance, fines, and detention. The legislation does not define what qualifies as an “undesirable website.”

In March 2017, Tajikistan’s Culture Ministry announced that books may not be brought into or taken out of the country without written approval, regardless of the language of the texts. Travelers are required to fill out an application “citing the name of the books, stating their language, the place of publication (and) the name of the authors…” Tajikistan's State Religious Affairs Committee and Interior Ministry have compiled a blacklist of banned books, most religious in nature, but also including books of spells.

In August 2018 a court sentenced Umar Murodov, a migrant worker, to five and a half years imprisonment for “insulting” President Rahmon on the social media site Odnoklassniki. A fall 2017 law amendment provided for criminal liability for “public insult or slander against [the President], the Founder of Peace and National Unity, the Leader of the Nation.”

In February 2020, the Supreme Court of Tajikistan found independent news outlet Akhbor.com, critical of the Tajik government, allegedly guilty of “serving terrorist and extremist organizations” and ruled to block the website.

The Dushanbe Shohmansur court in April 2020 sentenced a prominent independent journalist Daler Sharipov to one year in prison on charges of incitement of religious discord for printing copies of a dissertation. He was released early in 2021.

Tajikistan should:

- Rescind restrictions on the media, including the amendments that allow security services to monitor individuals’ online activities, and the July 2015 rule barring media from reporting news about government actions and policies without citing reports by the official state news agency Khovar;

- Revise the Penal Code to remove criminal sanctions for “insulting the president” or any government officials;

- Respect freedom of information, including on the internet, and tolerate all forms of legitimate speech, including criticism of the government and its policies;

- Release all journalists who have been imprisoned on politically motivated charges;

- Unblock websites to allow citizens free access to information.

PRISON CONDITIONS AND TORTURE IN CUSTODY

The Tajik government previously accepted several recommendations that called on it to “strengthen practical efforts to eliminate torture” (115.58), “to implement the recommendations of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and meaningfully investigate all allegations of torture” (115.61), to “continue the programmes to reform the judicial sector and penitentiary facilities” (115.80). In practice, the prison conditions remain abysmal, with regular reports of torture.

In November 2018 and May 2019, two prison riots in Khujand and Vahdat respectively, resulted in the deaths of at least 50 prisoners and five prison guards in circumstances which remain unclear. Authorities announced that it was necessary to use lethal force to put down apparently violent uprisings within the prisons. In both cases, dozens of prisoners were killed, which raised legitimate concerns about use of disproportionate or excessive force and unjustified resort to lethal force. Another 14 prisoners died of poisoning on July 7, 2019, allegedly as the result of eating tainted bread while being transported on a truck from prisons in Khujand and Istaravshan to prisons in Dushanbe, Norak, and Yovon.

During a prison visit in March 2019, imprisoned political activist and deputy head of the banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Mahmadali Hayit showed his wife, Savrinisso Jurabekova, injuries on his forehead and stomach that he said were caused by beatings from prison officials to punish him for refusing to record videos denouncing Tajik opposition figures abroad. Jurabekova said that her husband said he was not getting adequate medical care and fears he may die in prison as a result of constant beatings.

In May 2020, Radio Ozodi, the Tajik service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), reported that the Dushanbe Prison No.1 authorities had not introduced any measures to limit the spread of Covid-19. Prisoners were “required to gather in a small space for counting, most of the prisoners did not wear masks or gloves, and conditions … did not comply with sanitary standards.”

In June 2020, Rakhmatullo Rajab, a senior member of the IRPT jailed at the same prison, did not receive medical assistance when he showed Covid-19 symptoms, according to his son, Shukhrat. He and other prisoners were not tested for the coronavirus and relatives had to provide loved ones with medicines themselves. Each prisoner was also given one face mask; all inmates shared one thermometer. On July 13, Justice Minister Muzaffar Ashurion said in a press conference that 98 prisoners had been infected with pneumonia and 11 had died from it since the pandemic’s start. He denied the existence of the virus in detention facilities in Tajikistan.

In August 2020, prison authorities threatened prisoners to take them to a punishment cell if they communicated with jailed human rights lawyer Buzurgmehr Yorov, whose detention was deemed to be in violation of international law by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention in 2019. Prison authorities had earlier attempted to make Yorov denounce IRPT in writing and its exiled leader Muhiddin Kabiri, but he refused.

Tajikistan should:

- Publicly acknowledge the scope and gravity of the problem of torture;

- Ensure that thorough and impartial investigations are carried out into all deaths in custody as well as all allegations of torture and ill-treatment, and implement the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on Torture based on his 2012 and 2014 country visits;

- Take urgent steps to improve prison conditions to meet international standards and ensure prisoners are protected from the spread of the Covid-19 virus.

FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND BELIEF

Tajikistan previously accepted recommendations to “engage in bringing Tajikistan's legislation in line with the country’s international and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe commitments to protect freedom of religion” (118.10) and to “take the measures necessary to eliminate restrictions on freedom of worship” (118.47). Instead, the Tajik government severely curtails freedom of religion or belief, proscribing certain forms of dress, including the hijab for women and long beards for men. Salafism, a fundamentalist strand of Islam, has been officially banned in Tajikistan since 2011 and authorities regularly arrest individuals for alleged membership in Salafi groups.

In August 2017, authorities introduced a new law urging citizens to “stick to traditional and national dress.” While carrying no penalties, the law appears to be aimed at discouraging women from wearing the Islamic hijab[1]. Its introduction was accompanied by a street campaign in the capital and other cities, during which members of the State Women’s Committee stopped women on the street and urged them to replace their hijabs with the traditional Tajik scarf that leaves the neck uncovered.

In July 2017, Protestant Pastor Bakhrom Kholmatov was sentenced to three years in prison for “singing extremist songs in church and so inciting ‘religious hatred.’” Authorities raided Kholmatov’s church and neighboring affiliate churches in Sughd, harassing and beating church members. Kholmatov was previously arrested in April 2017 and kept in secret police custody. No action has been taken to investigate or prosecute the officials involved. He was released 3 months early in December 2019.

On January 2, 2020, a Law on Countering Extremism came into force which allows authorities to further curb free expression. Since then, according to RFE/RL, at least 113 people, including university staff, students, entrepreneurs and public sector employees, have been arrested across Tajikistan, allegedly for being members of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, which the government has banned in 2006.[2] Some accused were reportedly denied access to lawyers and their relatives.

In February 2020, at least 30 Brotherhood suspects were released after they had spent 10 to 20 days in detention. In March, a court in Khatlon region sentenced Komil Tagoev, an alleged member, to a year in prison following his earlier arrest on charges of “organizing activity of an extremist organization” and “religious discord.” In August, Sughd Regional Court in a closed trial sentenced another 20 people to between five and seven years in prison on extremism charges. One person was sentenced to a fine “for failing to report a crime.”

Tajikistan should:

Rescind laws curtailing the right of citizens to freedom of religion and belief, as well as the law prescribing acceptable dress codes.

- Rescind the Law on Countering Extremism and end restrictions of freedom of expression arising from the law;

- Ensure all detainees arrested under any laws enjoy and can enforce their right of access to a lawyer.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

The Tajik government previously supported recommendations to “take all necessary measures to fight against discrimination and violence against women” (A-115.37), to “carry out awareness raising campaigns for the prevention of domestic violence, particularly against women and girls” (115.63) and “so that law enforcement officials, medical personnel and jurists learn how to provide proper care to survivors of gender violence” (115.64), as well as to “establish a mechanism for the implementation of the law on domestic violence” (115.65).[3] However, domestic violence remains a serious problem in Tajikistan.

Despite a 2013 law on the prevention of violence in the family, domestic violence and marital rape are not specifically criminalized in Tajikistan. By late 2018, authorities had taken steps to combat domestic violence against women and children, operating more than 15 police stations staffed by female police inspectors who underwent training in gender-sensitive, community policing. However, survivors of domestic violence, lawyers, and service providers reported that the law remains largely unimplemented, as victims of domestic violence continue to suffer inadequate protection. Police often refuse to pursue investigations, issue protection orders, or arrest people who commit domestic violence, even in cases where the violence is severe, including attempted murder, serious physical harm, and repeated rape.[4] When police do get involved in family violence cases, they do so without adhering to international standards calling for a survivor-centered response and often mandate mediation for the couples involved, in contrast with international best practices, which encourage arrest and prosecution.

Tajikistan never declared a country wide quarantine during the pandemic and shelters and crisis centers continued to operate. Service providers reported that during the pandemic incidents of family violence escalated and acts of violence became harsher/crueler. While some women were able to escape violence and seek protection, many feared leaving the house due to control by their abusers and because of the risks associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. Service providers experienced high demand for remote phone consultations and support.

Tajikistan should:

- Amend the 2013 domestic violence law to explicitly criminalize domestic violence as a stand alone offence;

- Implement and enforce existing provisions of the domestic violence law;

- Reinforce protection and support for survivors of domestic violence by ensuring availability of comprehensive services including shelters and specialized psychosocial, medical, and legal services, including in rural areas;

- Provide targeted, mandatory capacity-building activities on the prevention and identification of, and the response to, all forms of gender-based violence, including domestic violence, for law enforcement and judicial officials.

[1] In 2018 the UN Human Rights Committee had found that a similar law in France banning the niqab “disproportionately harmed the petitioners’ right to manifest their religious beliefs, and that France had not adequately explained why it was necessary to prohibit this clothing”.

[2] https://www.upr-info.org/sites/default/files/document/tajikistan/session_25_-_may_2016/recommendations_and_pledges_tajikistan_2016.pdf

[4] https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/19/violence-every-step/weak-state-response-domestic-violence-tajikistan

[5] 5-Stan: Domestic Violence in Tajikistan During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Podcast. 09/02/2021