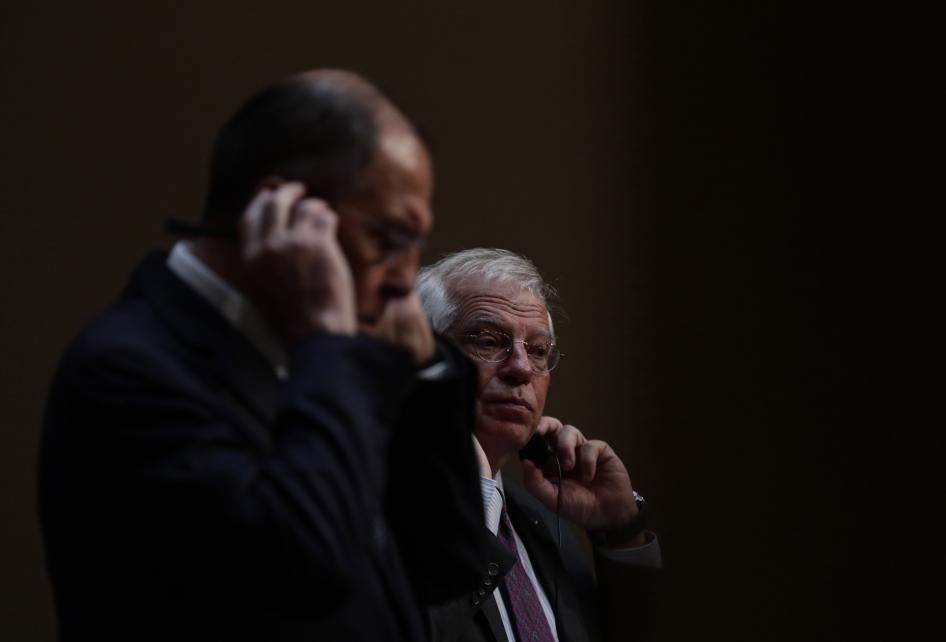

It’s an understatement to say that Josep Borrell’s first visit to Russia in his capacity as the European Union’s foreign affairs chief is a major event.

The EU’s relations with Russia hit a new low in January following the politically motivated arrest of the opposition leader Alexei Navalny right after his return from Germany, where he had been treated for a near-fatal poisoning.

The eyes of both top European policymakers and the Kremlin will be on Borrell.

But Borrell will also be scrutinized by the thousands of Russian citizens who are faced with new waves of repression because they stood up against corruption and injustice.

On Tuesday, a court in Moscow ruled to keep Navalny in jail for more than two-and-a-half years, after Russian authorities had struggled for the past two weekends to suppress peaceful protests across the country. Right after this ruling, thousands were back in the streets, gathering largely peacefully despite the risk of arrest. Police had already detained over 9,000 people, including scores of civic activists, such as Navalny’s key supporters, who were detained ahead of the protests in various parts of Russia. Many already face politically motivated administrative or criminal charges, including for violating regulations on mass gatherings or disobeying police orders. The scale of arrests and – in some Russian cities, police violence – was unprecedented. But the authorities failed to stifle the protesters’ voices.

If Borrell is to demonstrate a principled EU stance on its core human rights values, he should publicly and unequivocally reiterate the EU’s calls to free Navalny and drop charges against him. Borrell should press for an effective investigation into the credible allegations that Federal Security Service officers poisoned Navalny with Novichok nerve agent as he took a flight from Tomsk to Moscow in August. Borrell should also urge Russia to free all those arrested while protesting peacefully and stop harassing Navalny’s supporters and civic activists.

Borrell should also make it clear that he and the EU view the attacks on Navalny and the vicious crackdown on public protests as the tip of the iceberg of Russia’s deliberate and persistent efforts to silence democratic voices with increasingly restrictive laws and politically motivated prosecutions. New draconian legislation rammed through the parliament aims to deliver a crushing blow to Russia’s already severely encumbered civil society.

Since 2012, the government has used the “Foreign Agents” law to demonize groups that receive international funding and carry out advocacy or other work, including environmental and human rights activism. Scores of organizations were fined over not registering with the justice ministry as “foreign agents” or not displaying the toxic label on their websites, social media pages, and publications. Dozens of independent groups shut down, finding themselves unable to operate in this hostile environment.

To exacerbate the damage, toward the end of 2020, Russia’s government rammed through the parliament several additions to the already bulky and restrictive “foreign agent” legislation. Some of the amendments were adopted and entered into force by the end of December, and some are in the final stages of being adopted. The amendments drastically expand the scope of those that can be designated “foreign agents” to include a wider range of individuals and non-registered public associations. They also expand the notion of foreign funding to include vaguely worded “methodological and organizational support”. Failure to comply with the new regulations may lead to criminal prosecution and up to five years in prison.

Russian authorities have escalated the use of yet another deeply flawed law, which authorizes the prosecutor general to ban from Russia any foreign or international group perceived as harming Russia’s security. Last year, the authorities designated as “undesirable” three European organizations, including the Association of Schools of Political Studies of the Council of Europe. The law enables the government to prosecute Russians over any involvement with “undesirable organizations”.

In 2020, two activists were sentenced, and at least two more charged for their alleged association with Open Russia Civic Movement. An activist from Rostov-on-Don has already spent over two years under house arrest for participating in a public debate and reposting information about peaceful protests.

It is encouraging that Borrell framed his visit as an opportunity to pass a clear message on rights and freedoms.

Russia’s treatment of critics is arbitrary and unjustified, and at times even brutal. But as Russians from all walks of life find the courage to take to the streets and peacefully express their discontent, it is crucial for Borrell to make it clear to them that the EU hears their voices and supports their calls for justice, transparency, and free and fair elections in Russia.