Diplomats at the United Nations Human Rights Council don’t expect someone allegedly associated with a death squad to be among their colleagues. Yet that is the situation confronting officials in Geneva since Sri Lanka’s new permanent representative, C.A. Chandraprema, presented his credentials in November. The next session of the council beginning in late February presents a crucial opportunity to reverse the impunity that perpetually sets back the cause of justice in Sri Lanka.

Chandraprema is politely described as a veteran newspaper columnist and author. But for decades, he has also been known as Thadi Priyantha, an alleged member of the People’s Revolutionary Red Army (PRRA), a pro-government armed group accused of acting as a death squad in the late 1980s to combat an insurrection by left-wing youth in southern Sri Lanka.

The PRRA is accused of carrying out hundreds of killings in coordination with Sri Lankan security forces, targeting students, journalists, and lawyers. The group often left posters by the bodies of its victims, claiming responsibility for the attacks.

In 2000, Chandraprema was arrested by Sri Lankan authorities in connection with the 1989 murders of two human rights lawyers, Charita Lankapura and Kanchana Abhayapala. His arrest followed sworn testimony by a former senior police officer that Chandraprema was responsible for four murders. He was later released, after the attorney general reportedly determined that there was a lack of evidence.

Allegations of a cover-up ensued, reportedly because senior politicians were linked to the killings. These concerns were reinforced earlier this year when police submitted to a parliamentary committee responsible for vetting high-level appointments a document that claimed Chandraprema had never been the subject of a criminal complaint.

Impunity for Multiple Top Leaders

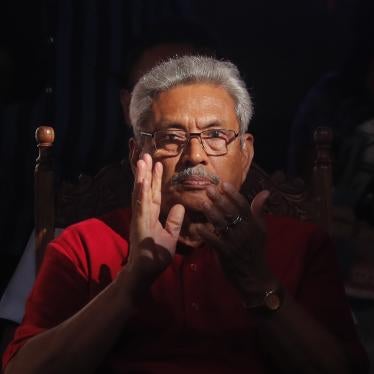

Chandraprema is not the only person accused of serious abuses who has been appointed to a senior role in the administration of President Gotabaya “Gota” Rajapaksa. The president himself is accused of numerous abuses, including war crimes and other serious violations during the long conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, or LTTE, which was defeated in 2009.

Kamal Gunaratne, the defense secretary, commanded the 53rd division of the Sri Lankan army, which was alleged to have summarily executed captured fighters in the final months of the war. The United States has barred the current chief of the defense staff and commander of the Army, Gen. Shavendra Silva, from entering the United States due to “credible information of his involvement, through command responsibility, in gross violations of human rights, namely extrajudicial killings.”

As Sri Lanka’s permanent representative to the Human Rights Council in Geneva, Chandraprema’s brief includes persuading other countries to drop their longstanding demands for justice and accountability for alleged government war crimes and crimes against humanity.

LTTE and government atrocities have been extensively documented in U.N. reports, leading to a consensus Human Rights Council resolution in 2015 that was supported at the time by the Sri Lankan government of then-President Maithripala Sirisena. The government made commitments to discover the truth of what happened, hold those responsible accountable with international assistance, and provide victims and their families with justice and reparations.

In November 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa won the presidential election and just three months later announced that Sri Lanka was withdrawing from these commitments. This was unsurprising, as the worst abuses took place when he was defense secretary in the government of his brother, then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who is now prime minister.

Rare Justice — Undone

As if to rub salt in the wounds of victims, in March, Gota pardoned former Army sergeant Sunil Ratnayake, one of very few security forces members ever held accountable for violations. Ratnayake had been convicted in 2015 of the massacre of eight Tamil civilians, including children, in 2000.

Chandraprema is so close to Gota that he has written a book entitled “Gota’s War,” which glorifies the current president’s actions and dismisses allegations of war crimes.

The Sri Lankan delegation in Geneva says that the Rajapaksa administration will pursue its own justice process to address accusations of serious abuses. Yet claims that it is committed to “achieving accountability . . . through the appointment of a domestic Commission of Inquiry” are not plausible. A series of domestic commissions of inquiry under successive administrations have produced long reports but have been little more than time-wasting exercises that have produced nothing but bitterness and disappointment among victims.

The Rajapaksas have long resisted justice efforts and pledged to protect “war heroes,” a promise Gota made again in a chilling and defiant speech on Nov. 18. According to the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, Sri Lanka’s “security sector and justice system have been distorted and corrupted by decades of emergency, conflict and impunity. For years, political interference by the executive with the judiciary has become routine.” Even as it pledged in September to conduct a new inquiry, the government made clear that it was not serious, telling the Human Rights Council that allegations against senior military officers are “unacceptable” and without “substantive evidence.”

Instead of heeding empty pledges by Chandraprema’s delegation in Geneva, governments that believe in respect for human rights need to stand up in defense of the rule of law for the worst international crimes. At the next session of the Human Rights Council, due to begin Feb. 22, Human Rights Council members should back a new resolution to advance accountability for the atrocities committed in Sri Lanka, by mandating the Office of the High Commissioner to collect, preserve, and analyze evidence, and to report to the council on avenues to accountability. The high commissioner should also be mandated to continue her reporting on ongoing violations. That is the best way to honor victims, and to confront the alarming risk of future abuses.