September 22, 2020

Mr. Philip Eure

Office of the Inspector General for the New York City Police Department

New York City Department of Investigation

80 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

Dear Mr. Eure,

The undersigned coalition writes to urge your office to conduct an audit of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) Criminal Group Database[1] (the “Gang Database”).

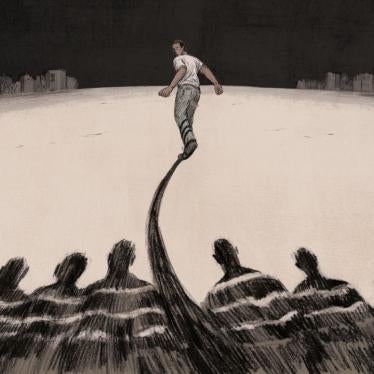

Specifically, we are concerned that the Gang Database is full of erroneous data, the result of ongoing and overbroad surveillance of Black and Latino communities, with consequences that follow them throughout their lives. Inclusion in a gang database, which requires no proof of criminal activity, can impact a person’s equal access to housing, schooling, recreation, naturalization, and more. We believe the NYPD Gang Database’s reliance on data collected using the vague, unaccountable, and subjective standards described below makes it inherently unreliable, and calls into question its use as an investigative tool.

Audits of similar gang databases in Los Angeles[2] and Chicago[3] have uncovered a number of fundamental deficiencies, from racial bias to falsified data to the lack of any mechanism for impacted people to challenge their inclusion. California Attorney General Xavier Becerra recently restricted the Los Angeles Police Department’s use of the state-wide CalGangs database after an audit revealed “significant misuse” of the database, “including entry of false information.”[4] An audit of the Chicago Police Department’s gang database by the city’s Inspector General reported erroneous data and racial bias, as well as vast data sharing with immigration authorities, school districts, and housing authorities.[5] This data sharing raises a number of concerns, from increased risk of deportation proceedings to an accelerated school-to-prison pipeline to potential risk of eviction. So widespread were the problems that the Chicago Police Department has decided to scrap the database.[6] They have announced their intent to create a replacement database, but it is unclear how the new database will avoid replicating the problems of its predecessor.[7] And in 2017, the Portland (Oregon) Police Bureau announced it was deleting its gang database, which disproportionately targeted communities of color and used overbroad indicators of gang affiliation.[8] The NYPD Gang Database is rife with many of the problems documented in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Portland, underscoring the urgent need for your office to conduct a thorough investigation.

This letter identifies five major areas of concern: racial bias; vague definitions of “gangs” and “crews”; overbroad criteria for inclusion in the database; lack of due process for individuals placed on the list; and the detrimental downstream consequences of inclusion on the list when it comes to criminal prosecution, education, housing, immigration proceedings, and more.

- The Gang Database disproportionately targets Black and Latino communities.

According to NYPD testimony at a 2018 City Council hearing, the database contains approximately 17,600 individuals.[9] And in 2019, the NYPD provided updated figures, testifying that there were 18,084 people in the database, including nearly 500 minors, some as young as thirteen.[10] The true number may be higher: the Intercept reports that according to data obtained by CUNY Law Professor Babe Howell under New York’s Freedom of Information Law (“FOIL”), there were 42,334 people in the database as of February 2018.[11] It is unclear what accounts for the disparity between the numbers reflected in the FOIL response and the department’s testimony to the City Council.

Regardless of the absolute numbers, according to the latest figures provided by the department, the database is 98.5% nonwhite, and a majority of those individuals are Black (66%) and Latino (31.7%).[12] By comparison, according to the latest survey by the American Community Survey, the overall New York City population is 24.3% Black and 29.2% Latino.[13] These are the same populations that were targeted under the unconstitutional stop-and-frisk program and face ongoing over-policing and surveillance in their communities.[14] The NYPD says that any racial bias in the gang database reflects the reality of how gangs recruit.[15] This explanation echoes the same flawed logic that was used to justify stop-and-frisk: that Black and Latinos were disproportionately stopped because they were more likely to engage in suspicious behavior.[16] In Floyd v. City of New York, Judge Scheindlin rejected this position, finding there was “no evidence that law-abiding blacks or Hispanics are more likely to behave objectively more suspiciously than law-abiding whites.”[17] Instead, the court ruled that this argument was “effectively an admission that there is no explanation for the NYPD’s disproportionate stopping of blacks and Hispanics other than the NYPD’s stop practices having become infected, somewhere along the chain of command, by racial bias.”[18]

The continued reliance on this justification amplifies the need to understand how the database may be leading to the same discriminatory outcomes as stop-and-frisk. Instead of accepting that certain racial groups are more prone to gang activity, the database’s racial bias may simply reflect where the NYPD chooses to prioritize law enforcement. At the same time, groups that are known for violence – such as white nationalist groups and biker gangs – are not in the database. The NYPD has confirmed that the Proud Boys, a far-right group, are not in the Gang Database,[19] and ongoing violence perpetuated by groups such as the mostly white Hells Angels[20] complicates the NYPD’s position that any racial bias in the database is explained by how gangs recruit.

- “Gang” and “Crew” are defined too broadly.

The NYPD has not issued a public definition of what constitutes a gang or a crew. However, internal police presentations reveal working definitions of each term. A “gang” is defined as “a group of persons with a formal or informal structure that includes designated leaders and members, that engage in or are suspected to engage in unlawful conduct.”[21] The definition of a “crew” is even more ambiguous, defined as “a group of people associated or classed together.”[22] Crews have “no initiations” or “consequences if you leave,” and might simply be associated by a block or apartment building.[23] Neither definition requires that a group have actually committed a crime or specifies the level of planning that justifies characterization as a criminal group. These broad definitions can lead to criminalization of friendships or community connections. Surveillance begins at an early age, as evidenced by the hundreds of kids that are included in the database, some as young as thirteen.[24]

The suspicious gaze cast on Black and Latino communities can result in the invention of criminal organizations that may not exist, further ensuring they remain subjects of ongoing surveillance. In one instance, a neighborhood mourning the death of a student by wearing lanyards with commemorative photos was characterized, possibly erroneously, as a gang. [25] There, a dozen men in East Harlem were arrested and charged with gang conspiracy for being members of a criminal organization that the NYPD and Manhattan District Attorney called the “Chico Gang.”[26] The gang was allegedly responsible for numerous violent retaliations for the killing of Juwan “Chico” Tavarez as well as “perceived slights against him after his death.” But it remains an open question whether this gang actually exists, and if the Gang Database tracks members of this group of youngsters. Residents of the Wagner Houses, where the gang allegedly operates, said they were not aware of such a gang, and that expressions like “Chico Gang” or “Chico World” were simply said among classmates and friends of Tavarez.[27]

- Criteria for inclusion are overbroad and ripe for abuse.

According to the NYPD, individuals are added to the Gang Database in three ways: (1) self-admission to an NYPD official during a “debriefing” or via social media posts; (2) identification by “two independent and reliable sources”; or (3) meeting at least two of six indicators of association.[28] Those indicators are: (1) presence at a known gang location; (2) possession of gang-related documents; (3) association with known gang members; (4) social media posts with known gang members while possessing known gang paraphernalia; (5) scars and tattoos associated with a particular gang; and (6) frequently wearing the colors and frequent use of hand signs that are associated with particular gangs.[29]

Each of these indicators raises serious concerns. Together they cast suspicion over entire communities. We urge your office to conduct an evaluation of these criteria.

- “Self-admission” is opaque and introduces serious due process concerns.

Self-admission to a member of the NYPD during a “debriefing” requires clarification. What constitutes a debriefing, and are any steps taken to corroborate an “admission” made by a person to police? Is the admission memorialized in a signed document? For example, Los Angeles prosecutors allege that field cards noting that individuals admitted to gang membership were contradicted by body camera footage showing that no admissions occurred or that individuals explicitly denied gang affiliation.[30]

Moreover, being part of a gang is not proof of involvement in any specific criminal activity, and individuals may not be aware of the significance of an admission of gang affiliation.[31] Accordingly, are individuals advised of their legal rights during “debriefings,” and are parents or guardians of minors notified of these debriefings and their potential consequences? If individuals can admit they are part of a gang, are they also allowed to request removal from the database when they are no longer a part of a gang or crew?

We have serious concerns that debriefings can be abused to obtain self-admissions that are coerced or fabricated. An audit of the Chicago gang database raised similar concerns with self-admission, reporting that “individuals may claim to be a member of a different gang than their actual affiliation, young people might experience peer-pressure to identify as a gang member even if uninvolved, and individuals may feel compelled by police to confess gang membership.”[32]

“Admitting” to gang membership through social media posts is even more alarming. Social media is ripe for misinterpretation by police and intentional misdirection on the part of the speaker. Studies of how police surveil social media consistently find that they “overwhelmingly lack the cultural competencies and knowledge necessary to accurately comprehend and regulate the cultural practices of urban youth.”[33] People may claim affiliation with a group for a number of reasons, from the need for protection to external pressure. At the same time, according to researchers, online puffery regarding the capacity for violence can be used to deter violence rather than incite it, suggesting that the link between online indications of gang membership and actual violence may be weak.[34]

Additionally, bragging by a group of friends calling themselves a gang, and overstating the threat they pose, may simply be a fictional projection to achieve status within a community.[35] Digital self-branding is a common practice among social media users, attempting to create a magnification of their real world self by curating how they present online.[36] Often, the gap between a person’s online and real world self is stark. In one instance, a young man posted a series of photos of himself holding a gun in various rooms in his home in order to give the impression that he was always armed and ready for a fight; in reality, he had taken all of the photos in the course of five minutes using a borrowed gun from a visiting cousin.[37] Emerging studies show that a number of non-gang affiliated youth will routinely “exaggerate their violent behaviors and even take credit for crimes they did not actually commit.”[38] We are concerned that ostensible self-admission via social media is too open to misinterpretation to be used as a standalone reason for inclusion into a Gang Database. This concern is amplified as law enforcement agencies expand their reliance on automated tools to monitor social media.[39]

- The identity of sources that can add individuals to the Gang Database remains unclear, and the sources may be unreliable.

We have concerns about the “independent and reliable sources” that are used to determine a person’s eligibility for inclusion in the Gang Database. According to NYPD testimony, the only individuals that can recommend someone for inclusion in the gang database are a Precinct Field Intelligence officer, a Gang Detective, or an investigator in the Social Media Analysis and Research Team.[40] Each recommendation is meant to include a written narrative and supporting documentation to justify an individual’s inclusion; this narrative is then reviewed by a supervisor in the Gang Squad for approval before inclusion in the Gang Database.[41] We urge your office to investigate how this requirement is implemented in practice and if there are other persons and organizations that also recommend individuals for inclusion in the Gang Database.

These questions are particularly salient in light of internal documents received through public records requests suggesting that additional organizations can recommend individuals for inclusion in the Gang Database, including the NYPD School Safety Division, the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, Neighborhood Coordination Officers, or an outside agency.”[42] Training documents for school safety personnel suggest looking for “warning signs” that simultaneously exploit stereotypes about Black and Latino communities (“unexplained wealth” and “trouble with police”) while linking ordinary teenage behavior with criminality (“changes in behavior”), but it is unclear if these personnel can make recommendations for individuals to be added to the Gang Database.[43] Similarly, FBI and DHS’s participation in joint gang investigations indicates that information is shared between NYPD and federal agencies, raising the question of whether these organizations can also recommend that individuals be added to the Gang Database.

- The indicators of gang affiliation are overbroad and ripe for abuse.

The six indicators of gang affiliation are overbroad to the point of being meaningless. For individuals who live in a community with a local gang or crew, it is almost impossible to avoid meeting two of the criteria for inclusion by having friends or family that are gang members. “Frequent presence at a known gang location” can simply refer to the area around an apartment building, or public spaces nearby. Similarly, “association with known gang members” assumes that any person who interacts with these individuals is part of their criminal organization, ignoring the reality that gang members have friends, family, neighbors, classmates, and coworkers. Especially in public housing projects, thousands of surveillance cameras blanket the grounds,[44] creating the opportunity for police to assess any handshake or social interaction as proof of gang affiliation.

These connections are even more attenuated for the indicator criteria focusing on social media posts where individuals are depicted with known gang members using “gang paraphernalia.” One New York teenager spent over a year on Rikers Island, based in large part on the district attorney’s incorrect assessment that he was part of a local crew.[45] The D.A. pointed to several Facebook photos of the teen with members of the crew and posts about the local crew that the teen had “liked” on Facebook, calling him a “known gang member.”[46] But while crew members were his friends and family, he was never part of the organization.[47] Similarly, the NYPD’s indicators of gang affiliation can create self-fulfilling prophecies where basic social media etiquette – liking a friend’s posts – is mistaken for membership in a criminal enterprise.

The remaining indicators of gang affiliation also raise overbreadth concerns. For example, without more information, it is difficult to understand what “gang-related documents” are and whether there may be innocuous reasons for possessing them. Similarly, the criteria for scars and tattoos associated with a particular gang, or the wearing of colors and gang signs, require individualized assessments to ensure that these indicators are not simply casting suspicion on a particular style of dress and individual expression that has little to do with gang affiliation. Even where a person leaves a gang, they may find it difficult or cost-prohibitive to remove a tattoo; there must be ongoing ways of ensuring these markers are not permanent labels of criminal association.

- Gang database entry and purging procedures offer little due process.

Individuals receive no notice that they are in the Gang Database, and there is no opportunity to challenge inclusion. This raises serious due process concerns, leaving impacted individuals (and, in the case of the hundreds of minors included, parents and guardians) without knowledge or recourse. The audit of the gang database in Chicago recommended that gang databases implement a process for impacted individuals to learn if they are in a gang database and establish a mechanism allowing them to challenging their inclusion.[48] Californians have the right to know if they are in the state-wide CalGangs database, and can petition for removal, although audits by the state Attorney General show that between November 1, 2017 and October 31, 2019, only twenty-four people successfully petitioned for removal.[49]

The NYPD claims it regularly checks entries every three years and on an individual’s twenty-third and twenty-eighth birthdays,[50] but there has been no independent assessment of the extent to which this practice is followed or whether the standard for ongoing watch-listing is necessary or appropriate. How often is intelligence updated, and what steps are taken to ensure information is up to date? While NYPD says they update individual entries, to what extent is the same process applied to understand whether particular gangs or crews are still in existence? In one instance, a community organizer with the Legal Aid Society was pulled over for a routine traffic stop; during his interaction with the officer, he discovered he was incorrectly listed in the Gang Database as a Crip gang member.[51] This data was doubly inaccurate: he had been associated with the Bloods gang fifteen years prior, but had long abandoned that world.

- Opaque data sharing can have downstream impacts on prosecution, access to housing, immigration proceedings, and more.

According to the NYPD, the Gang Database is accessed only by police personnel, and will not show up in a person’s criminal history or rap sheet or when the person is fingerprinted.[52] NYPD also claims that information from the Gang Database is not shared with the New York City Housing Authority or with federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement “to be used to initiate deportation proceedings [or] affect visa applications or citizen applications.”[53] However, there are instances where an individual’s gang affiliation has been shared with district attorneys as well as federal immigration authorities. Pressed at a City Council hearing, for instance, the NYPD admitted that it does occasionally share gang classifications with prosecutors.[54] Similarly, gang takedowns can be conducted in conjunction with federal immigration and law enforcement agencies, suggesting a greater degree of information sharing than is presented by the NYPD.[55] There is also inadequate transparency into whether information from the Gang Database is shared with federal agencies through the New York State Intelligence Center, New York City’s Joint Terrorism Task Force, or the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program. The audit of the Chicago gang database revealed that information was shared with over 500 external agencies (including immigration and criminal justice agencies); that the police department had inadequate control over this information sharing; and that these data sharing arrangements may have lasting consequences for impacted individuals and communities.[56]

While we do not have a full understanding of information flows from the Gang Database to prosecutors, gang affiliation has been used to keep individuals imprisoned pending trial.[57] New York does not have gang sentencing enhancements as in California and elsewhere,[58] but gang affiliation has been used as a factor in sentencing[59] and was even used as a factor in denying a prisoner early release because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[60] At the same time, it is unclear what happens to the dozens of individuals who are arrested as part of gang takedowns when the resulting prosecutions do not allege them to be gang members.[61]

Similarly, there is a serious risk that information shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement will be used to target undocumented residents,[62] an increasingly potent danger as the Trump administration seeks to demonize immigrant populations as national security threats by amplifying the threat of transnational gangs such as MS-13.[63] Information sharing with schools through School Resource Officers can also amplify the existing inequities of the school-to-prison pipeline for students of color. Finally, a person’s supposed gang affiliation and subsequent arrest can have other detrimental consequences for themselves and their families, especially if they live in NYCHA housing, which can permanently exclude “dangerous” individuals.[64] We urge your office to look into how information in the Gang Database is shared outside the department, including with prosecutors, city agencies, and federal agencies.

In summary, we have grave concerns that the NYPD Gang Database is operating to justify the ongoing surveillance of Black and Latino communities under the guise of gang policing. This surveillance brands the individuals living in these communities as inherently suspicious, limiting their ability to move freely or associate with their friends and relatives without the government’s watchful eye following them. We believe the Gang Database’s vague and subjective standards makes it unreliable as an investigative tool and results in ongoing discrimination against Black and Latino New Yorkers. An independent audit of the Gang Database is an important first step in providing necessary transparency into this surveillance tactic. It will enable the public, advocates, and lawmakers to make more informed decisions about whether this NYPD program should be continued at all.

We welcome the opportunity to answer any questions you may have, and to provide a number of additional resources and contacts that may be helpful as your office conducts an audit. We welcome your timely response and report.

Sincerely,

AI Now Institute at New York University

Arab Women’s Voice

Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF)

Brennan Center for Justice

Council on American-Islamic Relations, New York (CAIR-NY)

Demand Progress

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Fight for the Future

Human Rights Watch

Immigrant Defense Project

Mijente

National Action Network

National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild

National Lawyers Guild - New York City Chapter

New York Civil Liberties Union

Public Citizen

Restore the 4th

S.T.O.P. - The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project

SAFElab at Columbia School of Social Work

Tenth Amendment Center

The Bronx Defenders

The Policing & Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College

Brian Jefferson, Associate Professor at University of Illinois Urbana Champaign

Forrest Stuart, Associate Professor at Stanford University

Jeffrey Lane, Assistant Professor at Rutgers University

Kellie Leeson, in an individual capacity

Rashida Richardson, Visiting Scholar at Rutgers Law School

Ramy Aqel, in an individual capacity

Ruha Benjamin, Associate Professor at Princeton University, Ida B. Wells JUST Data Lab

Tahanie Aboushi, Civil Rights Attorney and Candidate for Manhattan District Attorney

[1] The gang database tracks information about New York City’s street gangs and crews. See Statement of Chief Dermot Shea, Chief of Detectives, New York City Police Department, Before the New York City Council Committee on Public Safety, Committee Room, City Hall, June 13, 2018, at 3.

[2] See Kristina Bravo, “LAPD suspends use of CalGang database months after announcing probe of officers accused of falsifying information,” KTLA5, June 20, 2020, available at: https://ktla.com/news/local-news/lapd-suspends-use-of-calgang-database-months-after-announcing-probe-of-officers-accused-of-falsifying-information/.

[3] See City of Chicago Office of Inspector General, “Review of the Chicago Police Department’s ‘Gang Database,’” April 2019, available at: https://igchicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/OIG-CPD-Gang-Database-Review.pdf.

[4] California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, “Attorney General Becerra Restricts Access to LAPD-Generated CalGang Records, Issues Cautionary Bulletin to All Law Enforcement, and Encourages Legislature to Reexamine CalGang Program,” July 14, 2020, available at: https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-becerra-restricts-access-lapd-generated-calgang-records-issues.

[5] See City of Chicago Office of Inspector General, “Review of the Chicago Police Department’s ‘Gang Database,’” April 2019, available at: https://igchicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/OIG-CPD-Gang-Database-Review.pdf.

[6] See Sam Charles, “Chicago police set to revamp controversial gang database,” Chicago Sun Times, February 26, 2020, available at: https://chicago.suntimes.com/2020/2/26/21155215/cpd-revamp-controversial-gang-database.

[7] See id; see also Mick Dumke, “Cook County Takes Steps to Erase Its Regional Gang Database,” ProPublica, available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/cook-county-sheriffs-office-database-new-ban-law (indicating Cook County’s plan to erase its gang database).

[8] See Carimah Townes, “Portland is saying goodbye to its controversial gang database,” The Appeal, September 12, 2017, available at: https://theappeal.org/portland-is-saying-goodbye-to-its-controversial-gang-database-e88e6c05262c/.

[9] See Statement of Chief Dermot Shea, Chief of Detectives, New York City Police Department, Before the New York City Council Committee on Public Safety, Committee Room, City Hall, June 13, 2018, at 4.

[10] See Testimony of Oleg Chernyavsky, Executive Director of Legislative Affairs, June 27, 2019. As with many NYPD surveillance tools, information about the Gang Database is limited. Even something as basic as the number of people in the database is contested and unclear.

[11] See Alice Speri, “New York Gang Database Expanded by 70 Percent Under Mayor Bill de Blasio,” The Intercept, June 11, 2018, available at: https://theintercept.com/2018/06/11/new-york-gang-database-expanded-by-70-percent-under-mayor-bill-de-blasio/.

[12] See Nick Pinto, “NYPD Added Nearly 2,500 New People to Its Gang Database in the Last Year,” The Intercept, June 28, 2019, available at: https://theintercept.com/2019/06/28/nypd-gang-database-additions.

[13] See 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, “Demographic and Housing Estimates,” New York City and Boroughs, available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/planning-level/nyc-population/acs/dem_2018acs1yr_nyc.pdf.

[14] See generally Floyd v. City of New York, 959 F.Supp.2d 540 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

[15] See Testimony of Oleg Chernyavsky, June 27, 2019.

[16] See e.g., Quint Forgey, “Bloomberg in hot water over ‘stop-and-frisk” audio clip,” Politico, February 11, 2020, available at: https://www.politico.com/news/2020/02/11/michael-bloomberg-stop-and-frisk-clip-113902 (“Ninety-five percent of your murders — murderers and murder victims — fit one M.O. You can just take the description, Xerox it and pass it out to all the cops … They are male minorities, 16 to 25. That’s true in New York.”).

[17] See Floyd v. City of New York, 959 F.Supp.2d 540, 588 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

[18] See id.

[19] See Nick Pinto, “NYPD Added Nearly 2,500 People to its Gang Database in the Last Year,” The Intercept, June 28, 2019, available at: https://theintercept.com/2019/06/28/nypd-gang-database-additions/.

[20] See Ed Shanahan and William K. Rashbaum, “Hells Angels Accused in Brazen Killing of Rival Biker Gang Leader,” New York Times, July 22, 2020, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/22/nyregion/hells-angels-bronx-pagans-murder.html.

[21] See Alice Speri, “New York Gang Database Expanded by 70 Percent Under Mayor Bill de Blasio,” The Intercept, June 11, 2018, available at: https://theintercept.com/2018/06/11/new-york-gang-database-expanded-by-70-percent-under-mayor-bill-de-blasio/.

[22] See id.

[23] See id.

[24] See Testimony of Oleg Chernyavsky, June 27, 2019.

[25] See Josmar Trujillo and Alex Vitale, “Gang Takedowns in the de Blasio Era: The Dangers of ‘Precision Policing,’” 2019 New York City Gang Policing at 12, available at: https://policingandjustice.squarespace.com/gang-policing-report.

[26] See Manhattan District Attorney Press Release, “DA Vance and Police Commissioner O’Neill Announce Indictment of 12 Members of East Harlem ‘Chico Gang,’” February 8, 2019, available at https://www.manhattanda.org/da-vance-and-police-commissioner-oneill-announce-indictment-of-12-members-of-east-harlem-chico-gang/.

[27] See Josmar Trujillo and Alex Vitale, “Gang Takedowns in the de Blasio Era: The Dangers of ‘Precision Policing,’” 2019 New York City Gang Policing, at 12, available at: https://policingandjustice.squarespace.com/gang-policing-report.

[28] See Statement of Chief Dermot Shea, Chief of Detectives, New York City Police Department, Before the New York City Council Committee on Public Safety, Committee Room, City Hall, June 13, 2018, at 4.

[29] Id.

[30] See Kevin Rector, James Queally, and Ben Poston, “Hundreds of cases involving LAPD officers accused of corruption now under review,” Los Angeles Times, July 28, 2020, available at: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-07-28/lacey-flags-hundreds-of-cases-linked-to-charged-lapd-officers-for-possible-review.

[31] This concern is amplified regarding “self-admission” regarding belonging to a “crew,” which can be nothing more than a loose collection of friends that live in a given area or housing complex.

[32] See City of Chicago Office of Inspector General, “Review of the Chicago Police Department’s ‘Gang Database,’” April 2019, at 24, available at: https://igchicago.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/OIG-CPD-Gang-Database-Review.pdf.

[33] Forrest Stuart, “Code of the Tweet: Urban Gang Violence in the Social Media Age,” Social Problems, Volume 67, Issue 2, May 2020, Pages 191–207, at 194 https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spz010; see also Forrest Stuart and Ava Benezra, “Criminalized Masculinities: How Policing Shapes the Construction of Gender

and Sexuality in Poor Black Communities.” Social Problems 65(2):174–90; Rios, Victor. 2011. Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys. New York: New York University Press.

April 27, 2019.

[34] See id. at 201.

[35] See Josmar Trujillo and Alex Vitale, “Gang Takedowns in the de Blasio Era: The Dangers of ‘Precision Policing,’” 2019 New York City Gang Policing at 7.

[36] See boyd, danah. 2014. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[37] See Forrest Stuart, “Code of the Tweet: Urban Gang Violence in the Social Media Age,” at 197.

[38] See id.

[39] See Sam Biddle, “Police Surveilled George Floyd Protests With Help From Twitter-Affiliated Startup Dataminr,” The Intercept, July 9, 2020, available at: https://theintercept.com/2020/07/09/twitter-dataminr-police-spy-surveillance-black-lives-matter-protests/.

[40] See Testimony of Oleg Chernyavsky, June 27, 2019.

[41] See id.

[42] See Josmar Trujillo and Alex Vitale, “Gang Takedowns in the de Blasio Era: The Dangers of ‘Precision Policing,’” at 8, available at: https://policingandjustice.squarespace.com/gang-policing-report.

[43] See id.

[44] See New York City, “De Blasio Administration Announces Completion of Camera Installation at 22 NYCHA Developments,” June 8, 2018, available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/396-17/de-blasio-administration-completion-camera-installation-22-nycha-developments.

[45] See Ben Popper, “How the NYPD is using social media to put Harlem teens behind bars,” The Verge, December 10, 2014, available at: https://www.theverge.com/2014/12/10/7341077/nypd-harlem-crews-social-media-rikers-prison.

[46] See id. It is unclear whether social media information collected by NYPD is shared with prosecutors through the Gang Database, and if the social media evidence used at trial is obtained independently of NYPD surveillance.

[47] See id.

[48] See City of Chicago Office of Inspector General Review of the Chicago Police Department’s “Gang Database,” at 13; see also Community Justice Project at University of St. Thomas School of Law, “Evaluation of Gang Databases in Minnesota & Recommendations for Change,” available at: https://www.leg.state.mn.us/docs/NonMNpub/oclc476283924.pdf (recommending timely notice and hearing requirements for ‘documented’ gang members).

[49] See California Attorney General, “Annual Report on CalGang for 2018,” at 2, available at : https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/calgang/ag-annual-report-calgang-2018.pdf, and California Attorney General, “Annual Report on CalGang for 2019,” at 3, available at: https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/calgang/ag-annual-report-calgang-2019.pdf.

[50] See Statement of Chief Dermot Shea, Chief of Detectives, New York City Police Department, Before the New York City Council Committee on Public Safety, Committee Room, City Hall, June 13, 2018, at 4.

[51] See Rocco Parascandola and Graham Rayman, “Advocates suspicious of NYPD’s gang database standard,” New York Daily News, June 12, 2018, available at: https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-crime/ny-metro-gang-data-base-nypd-shea-advocates-20180612-story.html.

[52] See Testimony of Oleg Chernyavsky, June 27, 2019.

[53] See Statement of Chief Dermot Shea, Chief of Detectives, New York City Police Department, Before the New York City Council Committee on Public Safety, Committee Room, City Hall, June 13, 2018, at 4; see also FN 2 at 50:10 (claiming that district attorneys do not have access to the Gang Database).

[55] See Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the State of New York, “NYC Drug Distribution Network and West Village Gambling Operation Dismantled Following Wiretap Investigation: 32 Arrested,” August 03, 2018, available at: http://www.snpnyc.org/nyc-drug-distribution-network-and-west-village-gambling-operation-dismantled/; see also U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “ICE HSI leads the largest street gang take-down in New York City history,” April 28, 2016, available at: https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-hsi-leads-largest-street-gang-take-down-new-york-city-history.

[56] See City of Chicago Office of Inspector General Review of the Chicago Police Department’s “Gang Database,” at 2.

[57] See e.g., Ben Popper, “How the NYPD is using social media to put Harlem teens behind bars,” The Verge, December 10, 2014, available at: https://www.theverge.com/2014/12/10/7341077/nypd-harlem-crews-social-media-rikers-prison.

[58] See California Penal Code Section 186.22.

[59] See e.g. U.S. v. Desuze, No. 15-CR-0287-4 (WFK), 2019 WL 4233431, at *4, (E.D.N.Y. Sep. 05, 2019) (“More generally, the Court’s sentence sends a message to other gang members that a life of crime carries a risk of punishment that outweighs any potential gains”); U.S. v. Artis, No. 15-CR-0287-1 (WFK), 2019 WL 3976663, at *4 (E.D.N.Y. Aug. 22, 2019) (“[The court] seeks to deter this Defendant from further criminal activity and encourages him to sever his ties to the OGC. It also seeks to protect the public from Defendant’s conduct in the future. More generally, the Court’s sentence sends a message to other gang members that a life of crime carries a risk of punishment that outweighs any potential gains”).

[60] See U.S. v. Amador-Rios, 18CR398S3RRM, 2020 WL 1849687, at * 2, (E.D.N.Y. Apr. 12, 2020) (“Were he to be released, there is grave concern that defendant will resume his activity on behalf of MS-13 and endanger the community as he has for so many years. For these reasons, the Court finds that there is no condition or combination of conditions that can reasonably assure defendant’s future appearance or the safety of the community”).

[61] See e.g., Babe Howell and Priscilla Bustamante, “Report on the Bronx 120 Mass ‘Gang’ Prosecution,” April 2019, available at: https://bronx120.report/the-report/#download, at 10 (“51 of the defendants swept up in ‘the largest gang takedown in New York City history’ were affirmatively not alleged to be gang members. For another 13 there is no clear allegation relating to gang membership. Their dispositions suggest they were not gang members. Fully half the defendants who were swept up in these raids were not alleged to be members of the gangs.”).

[62] See e.g. Hannah Dreier, “He Drew His School Mascot — and ICE Labeled Him a Gang Member,” ProPublica, December 27, 2018, available at: https://features.propublica.org/ms-13-immigrant-students/huntington-school-deportations-ice-honduras/.

[63] See Remarks by President Trump in Briefing on Keeping American Communities Safe: The Takedown of Key MS-13 Criminal Leaders, July 15, 2020, available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-briefing-keeping-american-communities-safe-takedown-key-ms-13-criminal-leaders/.

[64] See NYC Housing Authority, “Permanent Exclusion – Frequently Asked Question,” available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nycha/residents/permanent-exclusion-faq.page.