Police violence has a long history in the United States and remains a pervasive problem to this day. As recent research by Human Rights Watch has shown, it is inextricably linked to deep and persisting racial inequities and economic class divisions. For reform efforts to be meaningful and effective, they need to address those societal conditions.

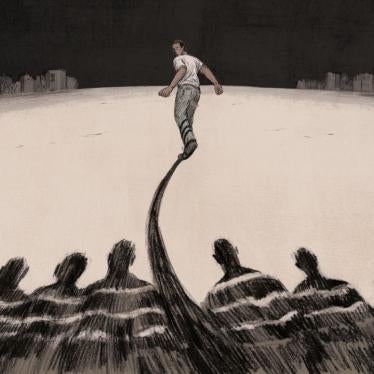

Too often police reform discussions in the United States focus on tactics that contribute to killings. Killings are only the tip of an iceberg of much more common daily interactions between police and Black, Latino, Native American, poorer people, and people with disabilities, that are coercive and often violent, even if they do not result in death or serious injury. Such interactions result in high rates of arrest and criminalization, again disproportionately impacting people from these communities, contributing to mass incarceration and devastating long-term consequences for those convicted and those close to them.

These patterns are themselves a product of generations-old systemic racial inequalities, laws, and policies that have prioritized policing and criminalization as the primary state response to a range of societal problems. They are also the result of an approach to policing in the United States that has too often relied on coercion and force and failed to ensure accountability for abuse. Reform efforts need to address these fundamental problems to be effective.

Human Rights Watch urges that United States police reform initiatives address three critical issues:

- Reducing the role of police in addressing societal problems;

- Investing in communities to advance public safety and equal rights; and

- Developing independent accountability and oversight mechanisms.

Instead of asking police to address societal problems, authorities should invest in services that directly address underlying issues such as mental health care and support, substance use disorder, and poverty. Making this shift, along with establishing effective and independent oversight bodies and the necessary legal tools to ensure accountability, is essential to limiting the police violence that has caused so much harm.

Reforming policing, even by reducing its scope and ensuring accountability, will not alone eradicate racially disparate results. Policing reflects and contributes to structural and other forms of racism. Authorities at all levels in the United States should adopt prompt and focused measures to understand and combat systemic racism in government, the economy, the health system, employment, housing and others, including, of course, the criminal legal system and policing.

Human Rights Watch makes the following 14 recommendations for police reform:

Reducing the Role of Police in Addressing Societal Problems

1. Reject overly aggressive policing tactics, like “stop and frisk” or those typically employed by police anti-gang units, that involve contacting, stopping, searching, and surveilling large numbers of people.

2. Decriminalize the possession of drugs for personal use and sex work, and stop enforcing laws in ways that effectively criminalize people for their poverty or lack of housing.

3. Explore the establishment of voluntary non-law enforcement and rights-based violence prevention programs, such as community-based mediation teams to address disputes within communities or interventions for youth who are at risk of joining or are already identified as being involved with gangs.

4. End any police involvement in enforcement of immigration laws.

5. End police involvement with people who are experiencing mental health crises.

6. Remove permanent police presence in schools.

Investing in Communities to Advance Public Safety and Equal Rights

7. Prioritize social services and community development in impoverished neighborhoods over funding the police:

- Develop and preserve affordable housing and social services where needed, instead of policing homelessness.

- Provide sufficient community-based voluntary drug treatment and harm reduction services, instead of policing drug use.

- Maintain effective, supportive, and voluntary mental health services in the community, instead of responding to mental health issues with policing.

8. Provide sufficient and adequate health care, education, and job training services for all people in jail and prison and for people upon their release and re-entry into the community.

9. Improve the quality of schools in impoverished communities, including funding quality after-school, preschool, and child-care programs for youth.

10. Fund, promote, and encourage local initiatives and enterprises that provide employment, training, education, and recreation for people in impoverished communities and for formerly incarcerated people.

11. Vastly reduce pretrial incarceration so that only those accused of serious crimes and found to pose a specific danger to others can be held in custody.

Developing Independent Accountability and Oversight Mechanisms

12. Establish independent community oversight bodies, with full access to police records, subpoena power, authority to conduct investigations and the power to discipline officers and command staff.

13. Collect data on police activities, disaggregated by race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, and other relevant demographic markers, and make it public.

14. Remove federal and state legal immunities that protect law enforcement officers from liability, as well as laws that keep police misconduct records inaccessible to the public.

Background and Case for Reform: US Police Violence

- Day-to-day abuse by police, especially toward Black, Latino, and Native American people, is pervasive; it often escalates and leads to killings.

- Mechanisms to hold police officers accountable for harming people are ineffective at best, encouraging officers to act with impunity.

- Policing in the United States emphasizes enforcing obedience through command and control, and responding to perceived disobedience with force.

- US society is extremely stratified by race; the way police are deployed and interact with communities compounds that stratification.

- Local, state, and federal governments in the United States fail to address societal problems through direct solutions, instead tasking police with handling them, which results in unnecessary interactions between police and the public that frequently escalate into conflict and violence.

- Governments should reduce the scope and responsibility of policing while redirecting funds to initiatives that support people and empower communities.

Day-to-day abuse by police, especially toward Black, Latino, and Native American people, is pervasive; it often escalates and leads to killings.

Killings by police officers of unarmed Black men have, in recent years, sparked media attention, public outrage, sustained protest and sometimes reform initiatives. The 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri led to protests across the country, a Department of Justice investigation, and efforts by the administration of then-President Barack Obama to examine policing tactics and culture.[1] The 2016 killing of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, caught on videotape and detailed in a 2019 Human Rights Watch report, has energized a local movement in that city that continues to press for oversight and accountability.[2] The callous killing on May 25, 2020 of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota,[3] revealed in graphic detail by cell-phone video, which followed the killing of Breonna Taylor on March 13 in her own home in Louisville, Kentucky,[4] sparked massive demonstrations across the United States and the world, leading a broad segment of the public to see the stark reality of US policing and to press policymakers to find ways to redefine the role of police in society in a way that protects public safety and human rights.

While data gathering on police killings and police violence overall is not comprehensive, some media that track such killings report that police kill about 1,100 people each year.[5] Black people make up nearly 25 percent of those killed, even though they make up only about 13 percent of the overall population. Police kill Native American people at comparably high rates.[6] Black people make up 37 percent of those killed who are unarmed.[7] George Floyd, Michael Brown, and Terence Crutcher, just a few of the names atop the list of Black lives taken at the hands of police, were all unarmed.

Police injure and kill people with disabilities at extremely high rates. Of all people shot and killed by police from 2015 through 2020, 22 percent had known mental health conditions.[8] An estimated one-third to 50 percent of all people involved in force incidents by police have some sort of disability, including mental health conditions.[9]

Lethal force is just a part of the story.[10] Lower level police violence occurs constantly, and in many cases amounts to excessive force prohibited under international human rights law.[11] This violence includes actions defined as “uses of force,” including kicks and punches, chokeholds, body weight, baton blows, bites by trained police dogs, and use of so-called “less lethal weapons,”[12] like Tasers and other “electronic control devices,” chemical sprays, and guns that fire rubber bullets or bean bags. Minneapolis Officer Derek Chauvin dropped his body weight on Floyd’s neck, which appeared to inhibit his breathing. Two other officers placed their weight on his body, adding to the pressure he felt.[13] The officers used lower-level force initially to take Floyd to the ground.[14]

Coercive actions by police that humiliate, demean, and terrorize people is also violent, often violate rights, and disproportionately target Black and Latino people. Arbitrary detentions and searches, abusive arrests, intrusive “well-being” checks for people assumed to have mental health conditions, racial profiling, selective enforcement of minor violations of law all contribute to an understanding among many Black people in the United States that they are not free and that police are intent on causing them harm.[15] A Department of Justice study revealed that Black people experience force by police two-and-a-half times more frequently per police contact than white people do.[16]

These “lower-level” violent actions build tensions that can escalate into more severe physical harm and at times death. Human Rights Watch reported in detail on the impact of these types of interactions specifically on Black people in Tulsa.

New York police officers detained Eric Garner accusing him of unlawfully selling cigarettes. When he protested his experience of persistent, demeaning harassment, one of the officers put him in a chokehold that killed him.[17] Like many people killed by police, Garner had disabilities, including asthma, diabetes, and a heart condition.[18]

The emergence in the 1990s of the “broken windows” theory of policing, which asserts that strict police enforcement of minor rule violations will deter more serious crimes, has contributed to increased negative police contacts and entire communities feeling they are being criminalized.[19] Los Angeles Police, for example, issued 12,000 citations for minor violations, primarily jaywalking, in the poverty-stricken Skid Row neighborhood in 2007, the first year of implementation of their “broken windows”-based “Safer Cities Initiative.” This rate of ticketing was over 50 times greater than that in the rest of the city.[20] Black people made up 40 percent of Skid Row residents subjected to this policing offensive, while making up only 9 percent of the city’s overall population.[21] This “broken windows” approach specifically targets particular neighborhoods and people within those neighborhoods for increased enforcement.

In a related policing strategy, known as “stop and frisk,” officers systematically detain or stop people with little or no suspicion that they have committed a crime, then conduct a “pat down” or sometimes more extensive searches for weapons or drugs.[22] This strategy is common even when police departments do not encode it as a formal policy. In New York City, where it was a formal strategy, Black and Latino people were approximately 90 percent of the people searched.[23] Police found contraband on only a very small percentage of people stopped, and slightly more frequently on white people than on Black people.[24]

A federal judge ruled New York’s explicit “stop and frisk” program to be unconstitutional, finding that it pressured officers to temporarily detain and search increasing numbers of people. The judge ordered the police department to modify the practice.[25]

Mechanisms to hold police officers accountable for harming people are ineffective at best, encouraging officers to act with impunity.

One substantial factor that empowers police violence is that there are few, if any, effective or independent accountability structures or laws, meaning that officers can act with impunity. This lack of accountability is a crucial part of how policing in the United States is designed. Legislators have passed laws, judges have imposed doctrines, police departments and prosecutors have implemented policies and practices that have all contributed to forming a system that protects officers and police departments from meaningful scrutiny.[26] Police unions negotiate contracts that give officers protection from discipline and accountability; they also lobby effectively for legislation that provides such protections.[27]

As a rule, police departments investigate and discipline their own employees.[28] They have incentives to exonerate individual officers to protect the department from liability and to insulate their behavior from exposure to scrutiny that might limit police power.

This self-policing results in few findings of misconduct. Investigators tend to believe officers over civilian witnesses. Human Rights Watch reviewed data on non-lethal use of force incidents provided by the Tulsa Police Department for the period 2012 to 2017. The data included 3,364 separate acts of force from 1,700 distinct incidents. Of those acts, the department found only two to be “out of policy,” and did not impose discipline in any case, despite the two findings.[29]

A review of New York Police Department complaint data from 2011 through 2015 revealed that 319 officers committed offenses for which they should be fired, but kept their jobs.[30] A 2008 audit of Internal Affairs investigations by the inspector general of the Los Angeles Police Department found that in nearly 50 percent of cases, investigators neglected to interview obvious witnesses, failed to follow investigative leads, or simply mischaracterized what witnesses said in their reports.[31] Most lower-level force incidents are not even investigated. A review of complaints against Chicago police officers from 2000 through 2005 revealed that of 56,459 total complaints, the department only sustained 2,320.[32]

Police investigate misconduct in ways that give the accused officers advantages other crime suspects do not have, and appear designed to establish innocence, not the truth.

For example, when Officer Betty Shelby shot and killed Terence Crutcher in Tulsa, she was not immediately arrested and questioned, as any ordinary crime suspect would have been. Instead, investigators gave her three days to review evidence to prepare her story, something typically denied crime suspects in such cases. Tulsa detectives allowed Shelby to watch the video evidence and explain it during her questioning. Though the district attorney did file charges in that case, the investigating detective testified that the shooting was justified, which doubtlessly contributed to her acquittal by a jury.

These investigative procedures contrast with practices in investigations of suspects who are not officers and in which the goal of the investigation is clearly to establish the suspect’s guilt. Police should conduct all investigations in ways that respect rights, presume suspects to be innocent, and seek to find the truth, rather than just make a case for the suspect’s guilt or innocence.

Police unions often negotiate these limits on investigations into their contracts, including requiring waiting periods before investigative questioning may begin, allowing officers full access to investigative material and other limits on investigative procedures.[33] The unions have historically opposed most efforts to hold officers accountable. Following Shelby’s killing of Terence Crutcher, the Tulsa Fraternal Order of Police (“FOP”) actively campaigned to sway public opinion leading up to her trial and pressured the district attorney to dismiss the charges.[34] The Tulsa FOP has a long history of opposing reform efforts, including actively seeking the ouster of reform-minded Chief Drew Diamond in the early 1990s and more recently stopping the mayor’s efforts to establish a police oversight body.[35] Police unions have a long history of lobbying for legislation that protects officers and departments from scrutiny.[36]

Prosecutors rarely file charges against officers.[37] A study of police killings across the United States from 2005 through 2018, occurring at a rate of around 1,000 per year, found that prosecutors filed murder or manslaughter charges only 97 times, resulting in 35 convictions of some charge and 42 acquittals or dismissals.[38]

From 2005 through 2014, police officers in Washington State killed about 215 people, a disproportionate number of them being Black, but prosecutors only brought criminal charges against one.[39] Similarly, in Utah from 2010 through October 2014, police killed 45 people, but prosecutors filed charges only against one, whose case was dismissed by the judge.[40] Prosecutors in New York did not file any charges against Officer Daniel Pantaleo for his 2014 videotaped killing of Eric Garner. On-duty New York Police officers killed people 179 times in the preceding 15 years, but prosecutors brought only three criminal indictments, netting one conviction with a sentence of community service and no jail time.[41] Of those killed, 86 percent were Black or Latino.

While law enforcement officers have killed hundreds of people in Los Angeles County since District Attorney Jackie Lacey took office in 2012, she has not filed a criminal case against any of them.[42] This refusal to file cases includes the killing of Brendon Glenn in which video-taped evidence shows Officer Clifford Proctor shooting Glenn twice in the back, and refutes his claim that Glenn was reaching for his gun. Even the police chief and Los Angeles Police Commission recommended filing criminal charges in that case.[43]

One explanation for prosecutors’ failure to bring charges against police officers is that they are not fully independent of police. Rather, they depend on maintaining close working relationships with the officers and departments that essentially create a conflict of interest.[44] Prosecutors may not want to jeopardize that relationship by aggressively investigating and prosecuting cases, or they may simply feel an affinity toward the officers that they rely on to help them in nearly every other case that they bring.

Beyond the lack of criminal prosecutions, other systems, and laws shield police from accountability. Civil lawsuits can provide an avenue for individuals harmed by police to get compensation and punitive damages from officers. But most, if not all, municipalities will pay those damages so the money judgment does not directly impact officers and ultimately comes from taxpayers.[45] In theory, an officer whose actions result in lawsuits that cost the department money would face discipline. In practice this does not necessarily happen.[46]

It is also difficult to bring successful lawsuits. A variety of legal standards favor law enforcement. Most striking are the various immunities given to police. States have protections that limit the right to sue police under state law.[47] Most police litigation is brought in federal court under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42 US Code section 1983. However, the legal doctrine of qualified immunity, developed by judges and not legislators, allows judges to dismiss cases even when a police officer is proven to have violated a constitutional right, if the person bringing the case cannot show that a previous case “clearly established” the existence of that right so that a “reasonable” officer would have known it was a violation.[48] In practical terms, this doctrine allows a judge who favors law enforcement to dismiss without trial a lawsuit alleging a valid constitutional violation, if that judge can point to a factual difference between this violation and any past violation found by a court. How substantial a difference largely depends on the discretion of the judge.

In 2018, the United States Supreme Court upheld dismissal of a case based on qualified immunity when the officers shot a person who was on the opposite side of a fence from them holding a knife at her side standing six feet away from a person who was telling the police to be calm—because these precise facts had not been decided before in another case.[49] The Supreme Court very recently declined to consider several cases seeking to overturn aspects of qualified immunity, but there are proposals in Congress to strike down the doctrine through legislation.[50]

Adding to the structures that support impunity are various legal and contractual provisions that favor secrecy.[51] In New York, section 50a of its Civil Rights Law prevented public disclosure of police officer disciplinary records for decades.[52] It even prevented such disclosure in court without a court order. Legislation to reverse section 50a stalled for years, but recently passed in response to the protests.[53] California has had extreme rules hiding police officer complaint and misconduct records from public view.[54] These rules were only recently modified in a limited way.[55] Some California police departments responded to the change requiring more transparency by destroying records or refusing to disclose them.[56] Many other states similarly provide special legal protections for police officers facing scrutiny for potential misconduct.[57] Police unions have lobbied for these types of protections across the United States.[58] Federal courts allow more broad disclosure of complaint histories in the course of litigation, but impose strict protective orders to prevent litigants from making that information public.[59]

Officers who do face discipline from their departments or termination of employment can generally go work for other departments in other jurisdictions.[60]

These rules serve to protect individual officers from scrutiny and accountability for their misconduct and to protect police departments from liability.

Policing in the United States emphasizes enforcing obedience through command and control, and responding to perceived disobedience with force.

Police officers in the United States tend to see any disobedience as a threat and are authorized to use force to overcome any perceived threat. This authorization comes from laws that allow them to use force to make arrests, to prevent escape, and to defend themselves while making arrests.[61] These laws give officers the flexibility to easily create narratives justifying their decisions to use force. Further, police training emphasizes the use of physical force.[62] The result is that even minor questioning of their authority can result in an aggressive response. Force becomes normalized and is highly valued.

The killing of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa is a case in point. Officer Betty Shelby told Crutcher to get down on the ground. Whether he heard her or not, he did not do so. Instead he walked back to his SUV with his hands in the air. Shelby testified that she was extremely scared, based on this action, and thought he would reach for a weapon. She testified she shot him because of this fear and that she had been trained to use such force in response to the perceived threat.[63]

In another incident highlighted in Human Rights Watch reporting, Tulsa officers had a man handcuffed and leaning against his car as they searched him. He told them to stop bending his wrists. The officers said, “Quit clutching up on me. You’re not going to like what happens” and continued bending his wrist and pushing him against the car. They then threw him to the ground and pepper-sprayed him in the eyes. Later, one officer described him as “giving us shit.”[64] The handcuffed man was not actually a threat to the officers. In that same incident, several officers were present and participated, including a training officer who described it as a “fight.”

The unwillingness to intervene by criticizing or restraining abusive fellow officers makes police violence more likely. In Minneapolis, two of Officer Chauvin’s partner officers helped him to pin George Floyd down and a third focused entirely on monitoring witnesses. None of them took any steps to help Floyd, even as the witnesses begged Chauvin to get off of Floyd’s neck.[65] Officers rarely take steps to restrain their colleagues and when they do, it often has negative consequences.[66] Some who have reported misconduct or intervened have been ostracized by their fellow officers, denied back-up in the field, retaliated against, pressured to retire, and even fired.[67]

A movement to train officers to act as “guardians” instead of “warriors” has become popular among reformers in recent years, as exemplified by the Obama-era Commission on 21st Century Policing.[68] The basis of these types of reforms are the principles of “community policing,” in which officers take less aggressive approaches to people and work together with certain community leaders to solve problems. Officers are often said to take the role of social workers.[69]

However, where Human Rights Watch has examined such community policing reforms, the impact has been limited at best. Tulsa has formally adopted nearly all of the 21st Century Policing recommendations, but in our research there we found that little changed in the style of policing as a result; indeed, even the reforms themselves tended to focus on improving community perceptions of the police department rather than changing behavior.[70] The police force ended up with more officers but not more oversight.

In Los Angeles’ Skid Row, community policing has been associated with the “broken windows” approach to problem solving in which police respond to property owners to solve problems of homelessness through enforcement actions, like ticketing and property confiscation.[71] Studies of community policing in Seattle and Los Angeles concluded that police simply decided who constituted community, excluding critical voices or favoring commercial and property-owning interests, and worked for their benefit without otherwise changing their behavior or giving up any existing powers.[72]

Given how deeply ingrained command-driven approaches to policing are in the United States, reforms that focus primarily on changing policing culture are likely to have little effect. Former New York Police Commissioner and Los Angeles Police Chief William Bratton, a leading proponent of “community policing,” said, “In a nutshell, cops like making arrests. That’s what they do.”[73]

Nor is it useful to have police take over social work functions, as some reformers suggest.[74] Social work requires lengthy training and expertise, and compliance with ethical rules that generally run counter to the police officer’s mandate to enforce laws through authority and force.[75] While social workers also can be coercive and discriminatory, police should not take on their role.

US society is extremely stratified by race; the way police are deployed and interact with communities compounds that stratification.

Black and Native American people and, to a slightly lesser extent, Latino people overall have higher rates of poverty than white people and lack access to power.[76] A history of slavery, land theft, forced relocation, legalized segregation under “Jim Crow” laws, illegal segregation and discrimination, practices like redlining and employment and housing discrimination, lack of intergenerational wealth, deindustrialization, and unequal funding of services like schools and health care have all contributed to this racial stratification of US society, which amounts to racial discrimination under international human rights law.[77]

Human Rights Watch’s report on policing, race, and poverty in Tulsa revealed tremendous differences in poverty between Black and white people in the city.[78] It showed that Black people have vastly higher unemployment rates; a higher percentage live below the poverty line; and their median income is half that of white people. These differences reflect the rest of the country. Black people have shorter life expectancies, with differences as great as 17 years between some white and Black neighborhoods in Tulsa. They attend underfunded, highly segregated schools and are more likely to lack access to healthy food. This poverty helps to explain higher crime rates, as lack of opportunities increases the likelihood people will pursue illegal means of survival, including engaging in the drug trade and other underground economies, and desperate circumstances enhance tensions that lead to violence.

The criminal legal system enforces a cycle of poverty. Arrests lead to jailing and pretrial incarceration, which keeps people in jail who have not been convicted of a crime. Using money bail or predictive risk assessments to determine who is incarcerated pretrial is discriminatory and unfair, regularly resulting in coerced guilty pleas and exposing people to future arrests and jailing.[79] In addition to jailing, arrests and citations lead to court debt, which poor people cannot pay, exposing them to arrest warrants and further enforcement action.[80] Public order crimes, like trespassing and loitering, often related to poverty, homelessness and mental health conditions, make up a large percentage of arrests and other enforcement actions by police.[81]

Aggressive enforcement in poverty-stricken, primarily Black and Latino, neighborhoods criminalizes members of those communities, but does not help them. Arresting and jailing people for possessing drugs for personal use does not help them address substance use disorder if they have it and is in any case a disproportionate response to private behavior; arresting homeless people for trespassing does not help them find a safe and stable home.

Arrests and police violence, from low-level harassment (unnecessary stops, searches) to lethal force, disproportionately impact Black, Native American, and Latino people. Again, Human Rights Watch research in Tulsa showed that Black people were exposed to police violence at a rate 2.7 times greater than white people and were arrested at a rate 2.3 times greater.[82] Data indicated that Tulsa police conducted stops more than 10 times as frequently per capita in some majority Black and poor neighborhoods than they did in overwhelmingly white and wealthier neighborhoods.[83] A major California study revealed that Black people were subject to arrest and police violence, as well as detentions, searches, and handcuffing at much higher rates than white people, but that police were less likely to find illegal drugs or weapons on them.[84] Black and white people use drugs at equivalent rates, but Black people are nearly three times as likely as white people to be arrested for that use.[85] This pattern of racial bias is pervasive throughout the United States. A study of law enforcement agencies across the country found that 95 percent arrested Black people at higher rates than they did white people.[86]

Police participation in the enforcement of immigration laws, generally directed at non-white people, ranging from traffic stops that target Latinos for potential immigration violations[87] to turning non-citizens (including legal residents) over to immigration authorities following arrests and other forms of cooperation,[88] has served to criminalize segments of Black and Latino populations. In Tulsa, with its growing immigrant population, the Sheriff’s Department participates in ICE’s Section 287(g) program, under the federal Immigration and Nationality Act.[89] The program has given some law enforcement agencies license to racially profile Latinos.[90] Many local law enforcement agencies also have financial incentives to arrest non-citizens, with sheriff departments earning millions of dollars under contracts to lock up immigrants for ICE.[91] This enforcement results in people being held in jail and exposed to deportation for minor as well as major crimes, and for a high level of anxiety throughout immigrant communities that often make immigrants less willing to seek redress for serious crimes.[92]

Police target youth, particularly Black, Native American, and Latino youth. Curfew laws that forbid young people from being outside during nighttime hours have spread across the United States, allowing police to detain, search, cite, and arrest youth without suspicion of further criminal activity, despite the curfews’ questionable impact on lowering youth crime.[93] Youth are frequently tried as adults and sometimes sentenced to life sentences without possibility of parole.[94] While youth incarceration rates have dropped over the past 25 years, dramatic racial disparities persist.[95] Native American youth are incarcerated at a rate three times greater that white youth; Black youth are incarcerated at four times the rate. While rates of drug use are fairly similar across races, Black youth are two-and-a-half times as likely to face arrest for drug possession as white youth.[96] Black youth are three times as likely to be arrested for loitering or curfew violations as young white people, reflecting the pervasive policing of their communities.[97]

About 30 percent of schools in the United States have a full-time police presence.[98] There is conflicting evidence as to whether police improve school safety, though studies have not accounted for non-police approaches to school safety, and there have been instances of violence by officers against students.[99] Assigning police to schools has resulted in increased suspensions, expulsions, and arrests, particularly for Black and Latino youth, pushing them into the criminal legal system when school discipline or more individualized attention might have resolved their issues.[100] Spending on school police could be directed into creating more supportive school environments that would improve safety without coercive means.[101]

“Tough on crime” approaches that in recent decades have focused on criminalizing drug use, sex work, immigration matters, and offenses associated with poverty have served as an excuse for heavy policing in communities of color. In turn, that policing has translated into massive and devastating harms disproportionately impacting Black and Latino communities, in the form of millions of arrests every year; convictions that saddle people with criminal records, making it difficult for them to access employment, housing, education, and wealth; and incarceration, depriving people of their liberty, deporting them from their communities, and separating them from their families.[102]

Local, state, and federal governments in the United States fail to address societal problems through direct solutions, instead tasking police with handling them, which results in unnecessary interactions between police and the public that frequently escalate into conflict and violence.

Lower-income communities throughout the United States need resources, support, and services. They need affordable housing to combat homelessness and housing insecurity. They need access to health care, including support for people with mental health conditions and substance use disorder. They need investment in schools, infrastructure, and employment development. Too often, local, state, and federal governments fund and task police to address these issues, rather than investing in solutions to these societal problems.

A good example is the defunding of mental health support and services. In Oklahoma, as detailed in Human Rights Watch’s 2019 report on Tulsa, a large percentage of people with mental health conditions do not get supportive services or needed treatment.[103] The state has cut funding for these services. In the absence of adequate services, police are sent to respond to people in crisis. But police lack the skills to do so humanely or effectively. The deputy chief of the Tulsa police department has acknowledged that much of their officers’ time is devoted to responding to calls related to perceived or actual mental health crises and that, generally, these calls should not be treated as law enforcement problems.[104]

In recent years, 20 to 25 percent of people killed by police in the United States had known mental health conditions.[105] In Tulsa in 2018, police tasered Joshua Harvey multiple times after police responded to calls reporting him walking down the middle of street, through traffic, having taken off his clothes.[106] The officers tried to grab him forcibly. He ran, broke through a glass door at a business and then was tasered. While Human Rights Watch cannot determine that the police actions caused his death, he did lose consciousness while they put body weight on him after cuffing him following multiple electric shocks. He died without regaining consciousness.

Governments should make voluntary supportive services available to people with mental health conditions and keep those services entirely separate from the criminal legal system. The criminal legal system should not be a replacement or a gatekeeper for social programs.

Similarly, local jurisdictions respond to homelessness with policing, rather than developing safe, affordable housing. And they enforce laws against sex work, vending, and other aspects of the underground economy, that essentially criminalize people for being poor and finding ways to survive.

The criminalization of substance use at all levels of government has been a major driver of policing: possession of drugs for personal use is by far the single most arrested for offense in the United States, though it has yielded no meaningful reduction in substance use disorder.[107] Even in the midst of an overdose crisis that is killing more than 60,000 people a year, it is extremely difficult to access voluntary evidence-based drug treatment in much of the country.[108]

There is substantial evidence that investment in education and employment development reduces crime. A study in Tulsa revealed that enhanced early childhood schooling was strongly associated with eventual reductions in violent crime.[109] Other studies show that improving school quality and academic attainment increases overall public safety by reducing crime.[110] Better employment opportunities associated with greater educational achievement diminish the lure of illegal activities by making people less willing to take risks and by removing the need to make money in the underground economy. Similarly, stable, good quality jobs correlate to less crime.[111] Research on the impact of employment and job training programs has demonstrated their strong impact on reducing crime.[112] Early intervention through schooling, social services, and investment in providing employment training and opportunities has been effective in diverting youth away from gangs.[113]

The US reliance on criminal law enforcement exacerbates the problems it is directed to address. Arresting and jailing people with mental health conditions is likely to make those conditions worse by increasing stressors and removing people from whatever support and services they do have. Arresting and ticketing homeless people can put them into court debt, and otherwise further destabilize their lives, decreasing their chance to find work or housing. Jailing people who are struggling with substance use disorder can put them into withdrawal, and increases the risk they will overdose and die when released.[114] People with criminal records find it harder to gain stable employment, increasing their likelihood of resorting to criminal means of survival.

Additionally, reliance on policing and enforcement requires funding. Policing budgets are typically among the largest if not the largest items of local government spending. The Minneapolis policing budget took up 35 percent of the city’s discretionary spending; Milwaukee’s took up 47 percent; Detroit, 30 percent; and Baltimore, just over 26 percent.[115] Los Angeles puts over 50 percent of its unrestricted discretionary spending into policing.[116] The New York Police Department only receives about 8 percent of the city’s discretionary spending, but that amounts to over $5.6 billion or $672 per person, among the highest totals in the United States.[117] By spending on law enforcement and directing police to address societal problems, governments have less funding available for solutions to those problems that are likely to make communities safer.

Governments should reduce the scope and responsibility of policing while redirecting funds to initiatives that support people and empower communities.

The protest movement that has emerged in the United States since the killing of George Floyd has articulated two powerful demands: (1) prosecute killer cops and, primarily, (2) defund the police. These demands call for holding officers accountable for their misconduct and re-envisioning public safety with much less reliance on police whose primary tools are command, arrest, and force.

In our report on Tulsa policing, Human Rights Watch recommended fundamental changes in policing and public safety that echo these demands.[118] And they are again reflected in the 14 recommendations set forth above.

Policymakers should go beyond superficial reforms of the sort that many advocates and public officials are currently proposing, some of which begin and end with narrow changes to police tactics such as requiring de-escalation when possible or banning chokeholds except when deadly force is authorized. These policy changes, while welcome enough, will have little effect because they rely too much on easily abused officer discretion and, without more fundamental change, can be replaced by other easily abused types of force application.[119] There is currently considerable momentum for police reform that should not be squandered on minor and ineffectual policy changes, or on increased police funding to implement them.

Where such policy changes occur, police do not need and should not receive additional funding for training or implementation; departments already have the resources and tools needed to implement such changes and, as detailed below, scarce funding would be better spent on housing, health, education, and the creation of job opportunities in affected communities.

The fundamental changes that are essential to addressing police violence and racial discrimination require strengthening affected communities through increased support for a range of community services, and shifting money away from policing to do so.

The United States relies too much on police to safeguard public safety and wellbeing. At its root, public safety comes from removing underlying drivers of crime and violence, and from professional responses from social workers, healthcare workers, trained community members, and others who have tools to solve people’s actual problems. Public safety may also be promoted by community institutions that resolve neighborhood disputes and promote safety in non-punitive and rights-respecting ways.

Some jurisdictions are already experimenting with this shift in public safety priorities. For example, a Eugene, Oregon program called Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) deploys medics and mental health professionals, usually instead of police, to situations involving people experiencing crises or with other needs.[120] Rather than prioritize obedience and control, these responders prioritize problem solving and claim to seek safety for everyone involved. Workers for CAHOOTS respond to calls, make basic medical evaluations and offer services if the person voluntarily accepts them.[121] They respond to approximately 20 percent of 911 calls in Eugene, and may be underused.[122] This program has a promising model, as long as the mental health professionals respect the autonomy and rights of the people they serve and do not recreate the same coercive approaches used by many police.[123]

Neighborhood peacekeeper programs, like “Ceasefire” in Chicago and “Safe Streets” in Baltimore, have also proven successful in reducing violence.[124] These peacekeeper organizations hire and train people from within a community, often with criminal and gang records, to intervene in and de-escalate disputes between people without the use of force, arrest or other coercion. Studies have shown reductions in shootings and killings where these programs have operated.[125] As long as these peacekeeper models respect and support the rights of the people they serve; they may be a great improvement on policing.

Officials in Los Angeles have pledged to move $250 million from the police budget into social services.[126] It is unclear whether they will follow through with the pledge or from what part of the police budget they will take the money. The amounts are just a fraction of the policing budget, but the decision to reallocate the funds reflects a growing understanding of the need to change priorities. Other jurisdictions across the country are considering similar funding reallocations.[127] Minneapolis is even proposing disbanding their police force altogether and replacing it with a community-based system of public safety.[128]

The call to lower the policing footprint, re-envision public safety, and invest in initiatives that support and develop communities did not begin with the death of George Floyd. Black Lives Matter and its partners proposed and campaigned for a “people’s budget” in Los Angeles that city officials ignored until the recent round of protests erupted.[129] Communities across the country have been advocating for similar priorities for years.[130]

George Floyd’s killing has opened the eyes of many people within the United States to the need to address the harms of racially biased, coercive policing and the underlying structural racism within which that policing exists.

[1] Larry Buchanan et al., “Q&A: What Happened in Ferguson?” New York Times, August 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/08/13/us/ferguson-missouri-town-under-siege-after-police-shooting.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[2] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2019), https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/12/get-ground-policing-poverty-and-racial-inequality-tulsa-oklahoma/case-study-us.

[3] Evan Hill et al., “How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody,” New York Times, May 31, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-floyd-investigation.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[4] Anna North and Fabiola Cineas, “Breonna Taylor was killed by police in March. The officers involved have not been arrested,” Vox, July 13, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/5/13/21257457/breonna-taylor-louisville-shooting-ahmaud-arbery-justiceforbre (accessed August 6, 2020).

[5] “Mapping Police Violence,” MappingPoliceViolence.org, https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/ (accessed August 6, 2020); “The Counted: People killed by police in the U.S.” Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-map-us-police-killings (accessed August 6, 2020); see also, Julie Tate, Jennifer Jenkins, and Steven Rich, “Fatal Force,” Washington Post, August 6, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/ (accessed August 6, 2020). The Washington Post tracker strictly documents police shootings resulting in death.

[6] “The Counted: People killed by police in the U.S.” Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-map-us-police-killings (accessed August 6, 2020).

[7] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 53.

[8] Julie Tate, Jennifer Jenkins, and Steven Rich, “Fatal Force,” Washington Post, August 6, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[9] David Perry and Lawrence Carter-Long, “The Ruderman White Paper on Media Coverage of Law Enforcement Use of Force and Disability,” Ruderman Family Foundation, March 2016, https://rudermanfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/MediaStudy-PoliceDisability_final-final.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[10] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

[11] Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, Havana, 27 August to 7 September 1990, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.144/28/Rev.1 at 112 (1990).

[12] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Guidance on Less-Lethal Weapons in Law Enforcement,” 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CCPR/LLW_Guidance.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[13] “New video appears to show George Floyd being kneeled on by 3 officers,” CNN, May 29, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2020/05/29/george-floyd-kneeled-on-by-three-officers-video-vpx.cnn (accessed August 6, 2020).

[14] Matt Stieb, “Body Cam Footage of George Floyd’s Arrest Has Been Released,” New York Intelligencer, August 4, 2020, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/08/body-cam-footage-of-george-floyds-arrest-has-been-released.html (accessed August 10, 2020).

[15] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 84-123.

[16] Ibid, p. 143.

[17] Josh Sanburn, “Behind the Video of Eric Garner’s Deadly Confrontation With New York Police,” Time, July 22, 2014, https://time.com/3016326/eric-garner-video-police-chokehold-death/ (accessed August 6, 2020); “’I can’t breathe’: Eric Garner put in chokehold by NYPD officer—video,” Guardian, December 4, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/video/2014/dec/04/i-cant-breathe-eric-garner-chokehold-death-video (accessed August 6, 2020).

[18] Dominic Bradley and Sarah Katz, “Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray: the toll of police violence on disabled Americans,” Guardian, June 9, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/09/sandra-bland-eric-garner-freddie-gray-the-toll-of-police-violence-on-disabled-americans (accessed August 6, 2020).

[19] Sarah Childress, “The Problem with ‘Broken Windows’ Policing,” Frontline, June 28, 2016, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/the-problem-with-broken-windows-policing/ (accessed August 6, 2020); Christopher Robbins, “What Bratton Isn’t Telling You About Broken Windows,” Gothamist, December 31, 2014, https://gothamist.com/news/what-bratton-isnt-telling-you-about-broken-windows (accessed August 6, 2020).

[20] Professor Gary Blasi and the UCLA School of Law Fact Investigation Clinic, “Policing Our Way Out Of Homelessness: The First Year of the Safer Cities Initiative on Skid Row,” September 24, 2007, http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/downloads/pubs/faculty/wolch_2007_report-card-policing-homelessness.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020), p. 6.

[21] Community Redevelopment Agency of the City of Los Angeles, “Los Angeles’ Skid Row,” October 2016, https://www.lachamber.com/clientuploads/LUCH_committee/102208_Homeless_brochure.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[22] Ashley Southall and Michael Gold, “Why ‘Stop-and-Frisk’ Inflamed Black and Hispanic Neighborhoods,” New York Times, February 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/17/nyregion/bloomberg-stop-and-frisk-new-york.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[23] New York Civil Liberties Union, “Stop-And-Frisk Data,” 2020, https://www.nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data (accessed August 6, 2020); The Center for Constitutional Rights, “Racial Disparity in NYPD Stops-and-Frisks,” January 15, 2009, https://ccrjustice.org/files/Report-CCR-NYPD-Stop-and-Frisk.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[24] Ibid, p. 4-5.

[25] Bernard Vaughan, “NYPD’s ‘stop-and-frisk’ practice unconstitutional, judge rules,” Reuters, August 12, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-newyork-police/nypds-stop-and-frisk-practice-unconstitutional-judge-rules-idUSBRE97B0FK20130812 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[26] Human Rights Watch, Shielded from Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States, (New York, Human Rights Watch, 1998), https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports98/police/uspo14.htm.

[27] Steven Greenhouse, “How Police Unions Enable and Conceal Abuses of Power,” New Yorker, June 18, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/how-police-union-power-helped-increase-abuses (accessed August 6, 2020); Christopher Ingraham, “Police unions and police misconduct: What the research says about the connection,” Washington Post, June 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/06/10/police-unions-violence-research-george-floyd/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[28] Michael Bell, “A cop killed my son. We can’t let police investigate themselves,” Washington Post, March 29, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-cop-killed-my-son-we-cant-let-police-investigate-themselves/2018/03/29/b00ff482-31df-11e8-8bdd-cdb33a5eef83_story.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[29] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 134-135.

[30] United States Commission on Civil Rights, “Police Use of Force: An Examination of Modern Policing Practices,” November 2018, https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2018/11-15-Police-Force.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020), p. 62.

[31] Joel Rubin, “Audit cites LAPD unit on reviews,” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 2008, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-feb-12-me-complaint12-story.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[32] Abdul N. Rad, “Police Institutions and Police Abuse: Evidence from the US,” (M.A. diss., University of Oxford, 2019) https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:d251393e-53e0-4c5e-a0ab-323b49768de2/download_file?file_format=pdf&safe_filename=Police%2BInstitutions%2Band%2BPolice%2BAbuse%2B-%2BEvidence%2Bfrom%2Bthe%2BUS%2B-%2BRG%2Bthesis.pdf&type_of_work=Thesis (accessed August 6, 2020), p. 6.

[33] Abdul N. Rad, “Police Institutions and Police Abuse: Evidence from the US”; Reade Levinson, “Across the U.S., police contracts shield officers from scrutiny and discipline,” Reuters, January 13, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-police-unions/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[34] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 169-170.

[35] Ibid, p. 173-174; Kevin Canfield, “FOP says it still opposes mayor’s plan for police oversight,” Tulsa World, August 13, 2019, https://www.tulsaworld.com/news/fop-says-it-still-opposes-mayors-plan-for-police-oversight/article_a22dcd22-0ad2-5ca7-83c8-4444c342d978.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[36] Steven Greenhouse, “How Police Unions Enable and Conceal Abuses of Power.”

[37] Human Rights Watch, Shielded from Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States.

[38] Philip M. Stinson, Chloe A. Wentzlof, and Megan L. Swinehart, “On-Duty Police Shootings: Officers Charged with Murder or Manslaughter 2005-2018,” Criminal Justice Faculty Publications (2019), https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1097&context=crim_just_pub (accessed August 6, 2020). The remaining 20 had not been resolved at the time of the study.

[39] Steve Miletich, Christine Willmsen, Mike Carter and Justin Mayo, “Why It’s Basically Impossible to Prosecute Police Killings in Washington State,” Governing, September 29, 2015, https://www.governing.com/topics/public-justice-safety/some-police-killings-nearly-impossible-to-prosecute-under-washington-states-unique-law.html (accessed August 6, 2020). Those charges resulted in acquittal.

[40] Erin Alberty, “Killings by Utah police outpacing gang, drug, child-abuse homicides,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 24, 2014, https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=1842489&itype=CMSID (accessed August 6, 2020).

[41] Sarah Ryley et al., “Exclusive: In 179 fatalities involving on-duty NYPD cops in 15 years, only 3 cases led to indictments—and just 1 conviction,” New York Daily News, December 8, 2014, https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-crime/179-nypd-involved-deaths-3-indicted-exclusive-article-1.2037357 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[42] Sam Levin, “Hundreds dead, no one charged: the uphill battle against Los Angeles police killings,” Guardian, August 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/aug/24/los-angeles-police-violence-shootings-african-american (accessed August 6, 2020).

[43] Cindy Chang, Kate Mather, and Marisa Gerber, “If D.A. Jackie Lacey won’t charge the LAPD officer who shot Brendon Glenn, some ask: When would she prosecute?” Los Angeles Times, March 18, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-lacey-police-shooting-20180318-story.html (accessed August 6, 2020); “LAPD chief’s letter on fatal Venice shooting,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 2016, https://documents.latimes.com/lapd-chiefs-letter-fatal-venice-shooting/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[44] Kate Levine, “Who Shouldn’t Prosecute the Police,” Iowa Law Review 101 (2016), https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/print/volume-101-issue-6/who-shouldnt-prosecute-the-police/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[45] Brentin Mock, “How Cities Offload the Cost of Police Brutality,” CityLab, June 4, 2020, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/06/police-brutality-lawsuits-cities-settlements-credit-ratings/612301/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[46] Joanna C. Schwartz, “What Police Learn from Lawsuits,” Cardozo Law Review 33 (2012): 841, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1640855 (accessed August 6, 2020), p. 844.

[47] See, for example, Nathan Solis, “California Police Granted Immunity from Pursuit Liability,” Courthouse News, August 13, 2018, https://www.courthousenews.com/california-police-granted-immunity-from-pursuit-liability/#:~:text=SAN%20FRANCISCO%20(CN)%20%E2%80%93%20California,state's%20highest%20court%20ruled%20Monday (accessed August 6, 2020).

[48] Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, “Qualified Immunity,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/qualified_immunity (accessed August 6, 2020).

[49] Kisela v. Hughes, 138 S.Ct. 1148 (2018) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/17pdf/17-467_bqm1.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[50] Josh Gerstein, “Supreme Court turns down cases on ‘qualified immunity’ for police,” Politico, June 15, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/15/supreme-court-qualified-immunity-police-cases-320187; United States Congress, “Ending Qualified Immunity Act,” https://pressley.house.gov/sites/pressley.house.gov/files/Ending%20Qualified%20Immunity%20Act_0.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020);

[51] United States Commission on Civil Rights, “Police Use of Force: An Examination of Modern Policing Practices,” p. 55-63.

[52] Alan Feuer, “Civil Rights Law Shields Police Personnel Files, Court Finds,” New York Times, March 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/30/nyregion/civil-rights-law-section-50-a-police-disciplinary-records.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[53] Innocence Staff, “In a Historic Victory, Governor Cuomo Signs Repeal of 50-A Into Law,” Innocence Project, June 9, 2020, https://www.innocenceproject.org/in-a-historic-victory-the-new-york-legislature-repeals-50-a-requiring-full-disclosure-of-police-disciplinary-records/(accessed August 6, 2020).

[54] Lorelei Laird, “California relaxes one of the nation’s most restrictive laws on police personnel records,” ABA Journal, March 1, 2019, https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/california-police-personnel-records (accessed August 6, 2020).

[55] California State Legislature, “California SB-1421: Peace officers: release of records,” enacted September 30, 2018, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB1421 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[56] Los Angeles Times Editorial Board, “Editorial: Police: Stop resisting the new disclosure law on officer conduct,” Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2018, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-police-disclosure-20181227-story.html (accessed August 6, 2020); Jesse Marx, “Getting Police Records is Still a Slog, One Year into New Transparency Law,” Voice of San Diego, December 30, 2019, https://www.voiceofsandiego.org/topics/public-safety/getting-police-records-is-still-a-slog-one-year-into-new-transparency-law/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[57] Eli Hager, “Blue Shield: Did you know police have their own Bill of Rights?” Marshall Project, April 27, 2015, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/04/27/blue-shield (accessed August 6, 2020).

[58] Ingraham, “Police unions and police misconduct: What the research says about the connection.”

[59] Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, “Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: Rule 26. Duty to Disclose; General Provisions Governing Discovery,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_26 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[60] Timothy Williams, “Cast-Out Police Officers Are Often Hired in Other Cities,” New York Times, September 10, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/11/us/whereabouts-of-cast-out-police-officers-other-cities-often-hire-them.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[61] “Examples of laws authorizing police force include: 2005 Florida Code Chapter 776, sections 776.05 and 776.07,” https://law.justia.com/codes/florida/2005/TitleXLVI/ch0776.html (accessed August 6, 2020); “Indiana Code Title 35, Section 35-41-3-3,” https://codes.findlaw.com/in/title-35-criminal-law-and-procedure/in-code-sect-35-41-3-3.html (accessed August 6, 2020); “Oregon Statute ORS section 161.235,” https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/161.235 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[62] Seth Stoughton, “Law Enforcement’s ‘Warrior’ Problem,” Harvard Law Review Forum, April 10, 2015, https://harvardlawreview.org/2015/04/law-enforcements-warrior-problem/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[63] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 51-53, 169-170.

[64]Ibid, p. 124-126.

[65] Valerie Edwards, “New video of George Floyd’s ‘murder’ shows cop Tou Thao ignoring bystanders’ desperate pleas to save the father’s life as white cop Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds,” Daily Mail, June 14, 2020, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8419707/Video-George-Floyds-murder-shows-cop-Tou-Thao-ignoring-bystanders-pleas-help.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[66] “Blue Wall of Silence: A curated collection of links,” Marshall Project, June 22, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/records/605-blue-wall-of-silence (accessed August 6, 2020); United States Commission on Civil Rights, “Police Use of Force: An Examination of Modern Policing Practices,” p. 57-58.

[67] United States Commission on Civil Rights, “Police Use of Force: An Examination of Modern Policing Practices,” p. 57-58.

[68] Seth Stoughton, “Law Enforcement’s ‘Warrior’ Problem.”

[69] Matt Vasilogambros, “Police Train to be ‘Social Workers of Last Resort,’” Pew Charitable Trusts, May 31, 2019, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/05/31/police-train-to-be-social-workers-of-last-resort (accessed August 6, 2020).

[70] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 177-184.

[71] Alex Vitale, “The Safer Cities Initiative and the removal of the homeless,” Criminology and Public Policy 9 (2010): 867, https://www.academia.edu/8551301/The_Safer_Cities_Initiative_and_the_removal_of_the_homeless_Reducing_crime_or_promoting_gentrification_on_Los_Angeles_Skid_Row (accessed August 6, 2020).

[72] Alex Vitale, “Five myths about policing,” Washington Post, June 26, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-policing/2020/06/25/65a92bde-b004-11ea-8758-bfd1d045525a_story.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[73] William J. Bratton et al., “This Works: Crime Prevention and the future of Broken Windows Policing,” Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute, April 2004, https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/sites/default/files/cb_36.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[74] “Why Police Officers are Taking On Social Worker Responsibilities,” Tulane University School of Social Work, January 19, 2019, https://socialwork.tulane.edu/blog/why-police-officers-are-taking-on-social-worker-responsibilities (accessed August 6, 2020).

[75] Sharon Kwon, “It’s Time to Defund the Police and Start Funding Social Workers,” HuffPost, June 11, 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/defund-police-social-workers_n_5ee12d80c5b6d1ad2bd82777 (accessed August 6, 2020); Greg Walters, “These Cities Replaced Cops with Social Workers, Medics, and People without Guns,” Vice, June 12, 2020, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/y3zpqm/these-cities-replaced-cops-with-social-workers-medics-and-people-without-guns (accessed August 6, 2020); Kelan Lyons, “Should police be social workers?” CT Mirror, June 12, 2020, https://ctmirror.org/2020/06/12/should-police-be-social-workers-reimagining-their-role-in-responding-to-mental-health-crises/ (accessed August 6, 2020); National Association of Social Workers, “Revised Code of Ethics,” https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English (accessed August 6, 2020).

[76] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 48-50.

[77] Calvin Schermerhorn, “Why the racial wealth gap persists, more than 150 years after emancipation,” Washington Post, June 19, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/06/19/why-racial-wealth-gap-persists-more-than-years-after-emancipation/ (accessed August 6, 2020); United States Congress Joint Economic Committee, “The Economic State of Black America in 2020,” https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/ccf4dbe2-810a-44f8-b3e7-14f7e5143ba6/economic-state-of-black-america-2020.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020). The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which the United States has ratified, prohibits policies and practices that have either the purpose or effect of restricting rights on the basis of race. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), adopted December 21, 1965, GA Res. 2106 (XX), annex, 20 UN GAOR Supp. (No. 14) at 47, UN Doc. A/6014 (1966), 660 UNTS 195, entered into force January 4, 1969, ratified by the United States on November 20, 1994, Part I, Article 1(1).

[78] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 30-50.

[79] “Human Rights Watch Memorandum of Support for Preservation of the New York Pretrial Reform Law,” Human Rights Watch news release, March 20, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/20/human-rights-watch-memorandum-support-preservation-new-york-pretrial-reform-law#

[80] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 61-83.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Darwin Bond Graham, “Black people in California are stopped far more often by police, major study proves,” Guardian, January 3, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/02/california-police-black-stops-force (accessed August 6, 2020).

[85] Human Rights Watch, Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/12/every-25-seconds/human-toll-criminalizing-drug-use-united-states.

[86] Brad Heath, “Racial gap in U.S. arrest rates: ‘Staggering disparity,’” USA Today, November 18, 2014, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/11/18/ferguson-black-arrest-rates/19043207/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[87] Associated Press in Phoenix, “Sheriff Joe Arpaio guilty of contempt for ignoring order to stop racial profiling,” Guardian, July 31, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/31/joe-arpaio-convicted-contempt-immigration-patrols (accessed August 6, 2020).

[88] National Immigration Law Center, “How ICE Uses Local Criminal Justice Systems to Funnel People Into the Detention and Deportation System,” March 2014, https://www.nilc.org/issues/immigration-enforcement/localjusticeandice/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[89] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 155-163.

[90] American Immigration Council, “The 287(g) Program: An Overview,” July 2, 2020, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/287g-program-immigration (accessed August 6, 2020).

[91] Gaurav Madan and Flor Garay, “End county sheriffs’ abusive agreements with ICE,” Washington Post, June 18, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/end-county-sheriffs-abusive-agreements-with-ice/2018/06/15/43056c26-681e-11e8-bf8c-f9ed2e672adf_story.html (accessed August 6, 2020).

[92] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 155-163; Human Rights Watch, Cultivating Fear: The Vulnerability of Immigrant Farmworkers in the US to Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2012), https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/05/15/cultivating-fear/vulnerability-immigrant-farmworkers-us-sexual-violence-and#1885; Human Rights Watch, A Price Too High, US Families Torn Apart by Deportations for Drug Offenses (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/16/price-too-high/us-families-torn-apart-deportations-drug-offenses#.

[93] Angie Schwartz and Lucy Wang, “Proliferating Curfew Laws Keep Kids At Home, But Fail to Curb Juvenile Crime,” National Center for Youth Law, https://youthlaw.org/publication/proliferating-curfew-laws-keep-kids-at-home-but-fail-to-curb-juvenile-crime/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[94] “List of Issues Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee During its Periodic Review of the US,” Human Rights Watch, January 14, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/01/14/list-issues-submission-united-nations-human-rights-committee-during-its-periodic.

[95] The Sentencing Project, “Still increase in racial disparities in juvenile justice,” October 20, 2017, https://www.sentencingproject.org/news/still-increase-racial-disparities-juvenile-justice/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[96] Ibid.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Cheryl Corley, “Do Police Officers in Schools Really Make Them Safer?” NPR, March 8, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/03/08/591753884/do-police-officers-in-schools-really-make-them-safer (accessed August 6, 2020).

[99] Matt Barnum, “Do police keep schools safe? Fuel the school-to-prison pipeline? Here’s what research says,” Chalkbeat, June 23, 2020, https://www.chalkbeat.org/2020/6/23/21299743/police-schools-research (accessed August 6, 2020); Amanda Petteruti, Education Under Arrest: The Case Against Police in Schools, Justice Policy Institute, November 2011, http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/educationunderarrest_fullreport.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020); Emily Owens, “Testing the School to Prison Pipeline,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (2016), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/pam.21954 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[100] Amanda Petteruti, Education Under Arrest: The Case Against Police in Schools; Cheryl Corley, “Do Police Officers in Schools Really Make Them Safer?”

[101] Ibid.

[102] Human Rights Watch, Nation Behind Bars: A Human Rights Solution (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2014), https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/2014_US_Nation_Behind_Bars_0.pdf.

[103] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 144-150.

[104] Ibid, p. 146.

[105] Ibid, p. 147.

[106] Ibid, p. 139-142, 148.

[107] Human Rights Watch, Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States.

[108] Rachel N. Lipari, Eunice Park-Lee, and Struther Van Horn, “America’s Need for and Receipt of Substance Use Treatment in 2015,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2716/ShortReport-2716.html#:~:text=the%20past%20year.-,In%202015%2C%20an%20estimated%202.3%20million%20people%20aged%2012%20or,who%20needed%20substance%20use%20treatment (accessed August 6, 2020).

[109] Arelys Madero-Hernandez, Rustu Deryol, M. Murat Ozer, and Robin S. Engel, “Examining the Impact of Early Childhood School Investments on Neighborhood Crime,” Justice Quarterly 34 (2016), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07418825.2016.1226935 (accessed August 6, 2020).

[110] Randi Hjalmarrson and Lance Lochner, “The Impact of Education on Crime: International Evidence,” DICE Report, February 2012, https://www.economics.handels.gu.se/digitalAssets/1439/1439011_49-55_research_lochner.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020); Lance Lochner, Enrico Moretti, “The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self-Reports,” The American Economic Review, March 2004, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~moretti/lm46.pdf.

[111] Sarah Lageson and Christopher Uggen, “How Work Affects Crime—And Crime Affects Work—Over The Life Course,” http://users.soc.umn.edu/~uggen/Lageson_Uggen_Handbook_12.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[112] Hannah Myers, “More jobs, less crime,” J-Pal, August 8, 2017, https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/8-8-17/more-jobs-less-crime; Gillian White, “Can Jobs Deter Crime?” Atlantic, June 25, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/06/can-jobs-deter-crime/396758/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[113] James C. Howell, “Gang Prevention: An Overview of Research and Programs,” OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin, December 2010, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/231116.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

[114] Ingrid A. Binswange, et al., “Release from Prison—A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates,” New England Journal of Medicine 356 (2010): 157–165, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2836121/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[115] Center for Popular Democracy, “Congress Must Divest the Billion Dollar Police Budget and Invest in Public Education,” June 10, 2020, https://populardemocracy.org/news-and-publications/congress-must-divest-billion-dollar-police-budget-and-invest-public-education (accessed August 6, 2020). These figures are for FY 2020, except for Minneapolis, which is for FY 2017 as more current data was not available.

[116] City of Los Angeles, “FY 2020-21 Proposed Budget,” April 2020, http://cao.lacity.org/budget20-21/ProposedBudget/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[117] Center for Popular Democracy, “Congress Must Divest the Billion Dollar Police Budget and Invest in Public Education.”

[118] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 210-215.

[119] “US: Reject #8CantWait Policing Program,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/09/us-reject-8cantwait-policing-program.

[120] Danielle Cohen, “Here’s How a 911 Call Without Police Could Work,” Gentleman’s Quarterly, June 12, 2020, https://www.gq.com/story/how-a-911-call-without-police-could-work#:~:text=While%20CAHOOTS%20(which%20stands%20for,that%20actually%20protect%20and%20foster (accessed August 6, 2020).

[121] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jesus Leon Monsalve, paramedic with CAHOOTS, Eugene, Oregon, July 8, 2020.

[122] Ibid.

[123] CAHOOTS workers do have the authority to refer people showing suicidal or homicidal intentions to a security unit that can detain them in mental health centers for 24 to 48 hours. Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jesus Leon Monsalve, paramedic with CAHOOTS, Eugene, Oregon, July 8, 2020. Though this rarely occurs, it does raise potential for abuse and violations of rights.

[124] Human Rights Watch, “Get on the Ground!” Policing, Poverty and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma, p. 203-4.

[125] Ibid, p. 203-204.

[126] James Rainey, Dakota Smith, and Cindy Chang, “Growing the LAPD was gospel at City Hall. George Floyd changed that,” Los Angeles Times, June 5, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-06-05/eric-garcetti-lapd-budget-cuts-10000-officers-protests (accessed August 6, 2020).

[127] “New York City Council proposes cutting $1 billion from NYPD budget,” CBS News, June 13, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/new-york-city-council-proposes-cutting-1-billion-from-nypd-budget/ (accessed August 6, 2020).; Sarah Holder, “The Cities Taking Up Calls to Defund the Police,” CityLab, June 9, 2020, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/06/defund-police-city-council-budget-divest-public-resources/612694/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

[128] Oliver Milman, “Minneapolis pledges to dismantle its police department—how will it work?” Guardian, June 8, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/08/minneapolis-city-council-police-department-dismantle (accessed August 6, 2020).

[129] Tyler Kingkade, “Los Angeles activists were already pushing to defund the police. Then George Floyd died,” NBC News, June 15, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/los-angeles-activists-were-already-pushing-defund-police-then-george-n1231104 (accessed August 6, 2020).