“I want to move on and feel a part of Abiy’s Ethiopia. I want justice and a chance to get better myself,” a survivor of torture told a colleague of mine last year. “But I don’t know where to get that help. I don’t want to keep being stuck in my own past.”

As Ethiopia commemorates the 29th anniversary of the collapse of the military dictatorship known as the Derg in 1991, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed should commit to addressing legacies of violence by providing space for dialogue and for victim-centered approaches aimed at truth, justice, redress, and healing.

While it is tempting to turn the page, asking people to simply forgive and move on isn’t so easy. Ethiopians have frequently called for both meaningful justice and a chance to tell their stories. If left unaddressed and without means for additional redress, competing narratives of historical injustices may continue to afflict society in various ways.

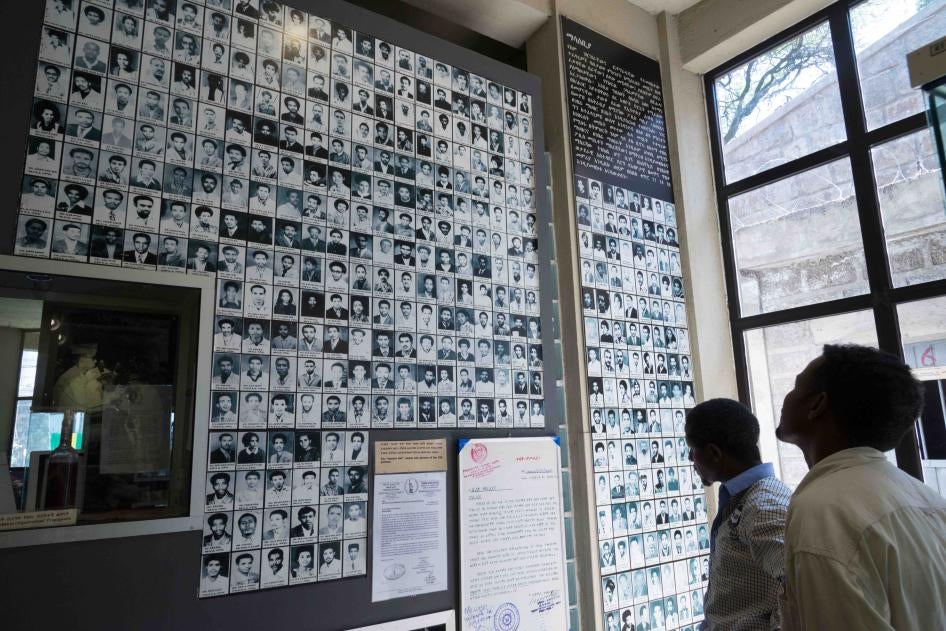

Between 1974 and 1991, the Derg regime, led by Mengistu Hailemariam, killed over 150,000 people including students, academics, and political opponents. The Derg also tortured, forcibly disappeared, and arbitrarily arrested many more. Mengistu fled to Zimbabwe in 1991 and was tried and convicted in absentia for genocide and war crimes by an Ethiopian court in 2006.

But state-sponsored killings and other serious abuses in Ethiopia did not begin, or end, with the Derg.

Students in the 1960s and 70s demanded equality for marginalized groups, freedom of speech, and land reform. Then, as in more recent years, demonstrators were met with bullets and faced mass arrests.

On May 28, 1991, liberation groups overthrew the Derg and formed a coalition government. The coalition pledged to establish human rights in the country and respect the rule of law. But it too committed decades of abuse. The military murdered, raped, and tortured civilians in Gambella and the Somali region, and enforced systemic repression around election periods.

Between 2014 and 2018, protesters, many of them students, took to the streets, echoing similar frustrations expressed by their counterparts in the 1960s.

Protesters initially expressed grievances over land reform, but their messages soon morphed into wider protests against decades-long repression. As in the past, security forces responded with brutal force, resulting in over 1,000 deaths, disappearances, and the imprisonment of thousands. The protests and crackdown eventually brought Abiy Ahmed to power.

There was hope that past crimes would finally be addressed under Abiy. In his inaugural address, he apologized for massive rights abuses and welcomed opposition groups back home. He’s since taken steps to resolve the lengthy border conflict with Eritrea and ushered in domestic reforms, actions that resulted in his receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

“I call on us all to forgive each other from our hearts — to close the chapters from yesterday, and to forge ahead to the next bright future through national consensus,” Abiy said in one address.

But to truly break with the past, Ethiopia needs to meaningfully pursue truth, justice, reconciliation, and redress —and not embrace one approach to the detriment of others.

Abiy continues to focus on reconciliation as his preferred approach for dealing with the country’s past. In late 2018, Abiy established a Reconciliation Commission principally tasked “to maintain peace justice, national unity and consensus and also Reconciliation among Ethiopian Peoples.” But the body was set up without broad-based public consultations, its mandate remains unclear, and some of its members lack the necessary technical expertise to effectively carry out the body’s fact-finding function.

The government also took some initial steps toward justice for past abuses. It arrested high-ranking officials of the former government for human rights abuses and corruption. But the arrests and charges appeared politicized. The government recently dropped most of the charges, citing the need for peace and reconciliation.

And yet, over the last two years, Ethiopia has experienced growing unrest and communal violence. The rise in violence, has led to deaths, displacement, and property destruction.

The government’s response to some of these challenges already show signs of backsliding. There are many credible reports of killings, torture, and arbitrary arrests by security forces. We have also documented shutdowns of phone and internet services in Oromia, and the arrests of journalists and opposition leaders and their supporters. A return to abusive practices is a painful reminder of the longstanding failure to effectively reform the security sector and address its culture of impunity.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the country now faces a public health crisis that has disrupted plans to hold greatly anticipated national elections initially scheduled for August. The delay has further exposed societal divisions, particularly among policymakers. Securing political consensus is deeply needed and would go a long way to facilitating, rather than hindering the potential of transitional justice measures to address harms and promote healing.

Ethiopia still has a way to go to fully learn and heal a divided nation that has suffered from legacies of abuse. Rebuilding trust in state institutions will be key. One step would be to clarify the mandate and scope of the Reconciliation Commission set up under Abiy. To ensure that it is a truly independent and inclusive truth-seeking process, the Commission should aim to consult with a broad range civil society, and victims’ and community groups.

Allowing these individuals and groups a voice in designing and carrying out the Commission’s work would not only pave the way for future accountability but revalues victims’ by giving them a safe platform to share their experiences. This approach would enrich the Commission’s work and legitimacy in the long run. The Commission’s future recommendations could also feed into judicial and security sector reforms, given their past and present abusive roles.

Abiy’s approach of national unity is an important message. But it is also one that expects Ethiopia’s society to heal without all the work that goes into making that possible.