(Tunis) – Tunisia still faces numerous hurdles to protecting its human rights gains nine years after Tunisians ousted the authoritarian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, Human Rights Watch said today in its World Report 2020.

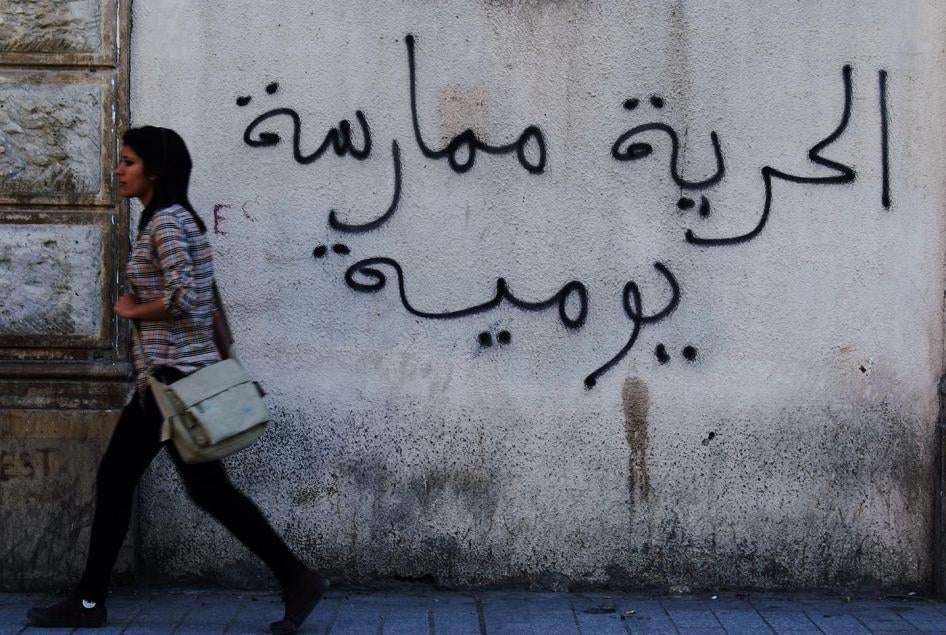

The authorities failed to scrap laws that are still being applied to punish Tunisians for peaceful criticism or for pursuing their private lives as they wish. The absence of a constitutional court, which the 2014 Constitution envisioned, deprives Tunisian citizens of the opportunity to challenge such laws.

“Tunisia’s progress on human rights will remain under threat until the authorities dismantle repressive laws and put in place key safeguards against abuses,” said Amna Guellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch.

In the 652-page World Report 2020, its 30th edition, Human Rights Watch reviews human rights practices in nearly 100 countries. In his introductory essay, Executive Director Kenneth Roth says that the Chinese government, which depends on repression to stay in power, is carrying out the most intense attack on the global human rights system in decades. He finds that Beijing’s actions both encourage and gain support from autocratic populists around the globe, while Chinese authorities use their economic clout to deter criticism from other governments. It is urgent to resist this assault, which threatens decades of progress on human rights and our future.

The Constitutional Court, as conceived by the constitution, could strike down existing and draft laws deemed unconstitutional, including those that would violate human rights. But parliament has failed in its duty to kick off the process of selecting its share of judges, and until the court is staffed, it cannot begin operations.

Tunisia made progress on transitional justice as the Truth and Dignity Commission (TDC), created under a 2013 transitional law to investigate human rights abuses from 1956 to 2013, completed its mandate and delivered its final report on March 26, 2019. The commission recommended judiciary and security force reforms to bar a return to systematic abuses, but the government has yet to act on its recommendations.

The 13 specialized court chambers created by the transitional justice law to try those responsible for past human rights abuses face numerous obstacles. The obstacles include an inability to compel the accused and witnesses to appear, as the police refuse to fulfill their duty to enforce summonses against uncooperative defendants.

Prosecutors in Tunisia have also charged bloggers, journalists, and social media activists under a number of penal code provisions. At least 14 were prosecuted under speech offenses in 2019, with six spending time in jail for criticizing state officials or revealing corruption by civil servants.

The authorities also prosecuted and imprisoned men suspected of being gay under Article 230 of the penal code, which provides for up to three years in prison for “sodomy.” The government also subjected suspects to anal tests to “prove” homosexuality, despite making a commitment during its Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council in May 2017 to end the discredited practice.

Since the declaration of a state of emergency in November 2015, which remains in effect, hundreds of Tunisians have faced arbitrary limitations on their movement when traveling inside and out of the country.

Parliament did not act on a draft law granting women equal rights in inheritance, which then-President Beji Caid Essebsi approved in 2018.