The Guinean government has razed thousands of homes in the country’s capital, Conakry, leaving families struggling to find adequate housing, Human Rights Watch said today. The government has provided no alternative accommodation or compensation to those displaced, in contravention of international human rights law.

Between February and May 2019, more than 20,000 people were displaced after bulldozers and other heavy machinery demolished buildings and forcibly evicted residents from the Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, Dimesse, and Dar Es Salam neighborhoods. Guinea’s government said that the land belongs to the state and will be used for government ministries, foreign embassies, businesses, and other public works.

“The Guinean government hasn’t just demolished homes, it has damaged peoples’ lives and livelihoods,” said Corinne Dufka, West Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The failure to provide alternative housing or even immediate humanitarian assistance to those evicted is a violation of human rights law and shows a blatant disregard for human dignity.”

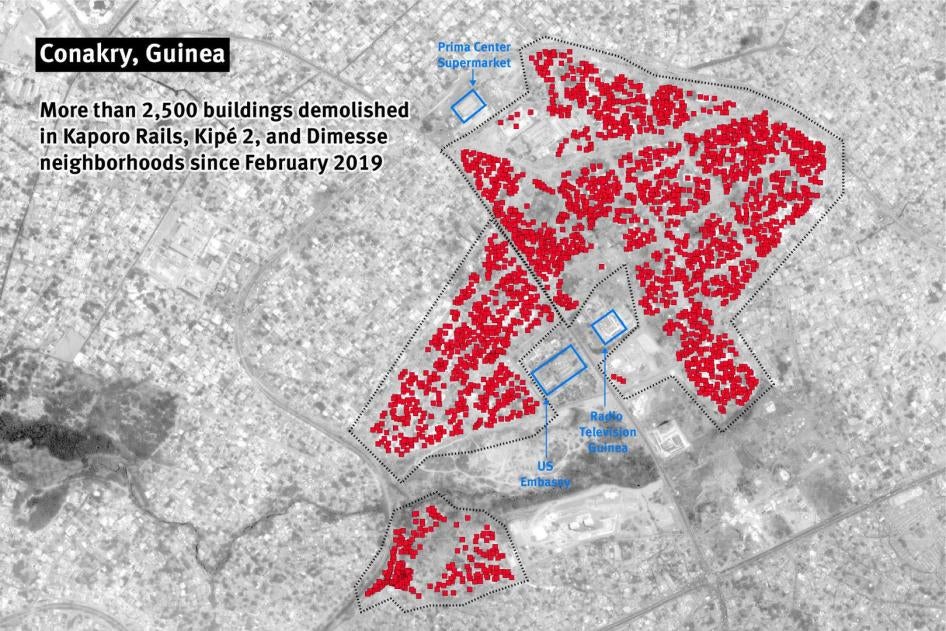

In March, April, and June, Human Rights Watch interviewed 40 victims of evictions in Conakry, as well as government officials, lawyers, nongovernmental organizations, religious leaders, and politicians. Human Rights Watch also reviewed satellite imagery, which showed that at least 2,500 buildings were demolished in the Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, and Dimesse neighborhoods in February and March and more than 385 buildings in Dar-Es-Salam in May.

The Ministry for Towns and Planning, which oversaw the evictions, maintains that the evicted areas were state land. However, many of the people whose homes were demolished said they had documentary proof that their families had decades-old property rights over the land. “It’s devastating to lose everything you have in 30 minutes,” said Makia Touré, a mother of six who said her family had lived in Kipé 2 since 1985.

International law also provides protections from forced evictions to any occupant of land, whether they occupy the land legally or otherwise. Governments should give victims adequate notice and compensation and should ensure that those evicted have access to alternative housing.

None of the evicted residents Human Rights Watch interviewed had received assistance from the government to find alternative housing, meaning that many were temporarily or, in some cases permanently, homeless once the evictions began. The Ministry for Towns and Planning said that residents either had other properties they could live in or were able to move in with their extended family.

However, Human Rights Watch interviewed several people who, weeks after the evictions, were living in flimsy wooden shelters or squatting in schools or mosques left standing after the evictions. “We have nowhere to go, so we’re just sleeping near to our ruined home,” said a Dar-Es-Salam resident, who slept with more than a dozen people in a wooden structure protected from the rain by canvas sheets.

Other residents who have found alternative accommodation have had to spread family members across different homes or leave Conakry altogether. “My family has left for the interior of the country,” said one Kipé 2 resident. “I’ve stayed near my home but I go to my neighbors’ houses to bathe and eat.” Some people’s new lodgings are far from their place of work and their children’s schools. “Children aren’t attending class anymore because they have left the area,” a middle school teacher from Kipé 2 told Human Rights Watch.

The Guinean government should ensure that residents who have been forcibly evicted get access to alternative housing of comparable quality to their demolished homes. Guinean authorities should also immediately take steps to create an effective and independent mechanism capable of promptly adjudicating and administering compensation claims related to the evictions.

“Any effort to redevelop land should respect the rights of existing residents,” Dufka said. “The government should immediately stop evictions until it finds a way to compensate those affected and provide them alternative housing comparable to what they left behind.”

Evictions in Koloma

The majority of the estimated 20,000 people evicted came from the Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, and Dimesse neighborhoods, which are 15 kilometers from the center of Conakry, close to the United States Embassy and the headquarters of Guinea’s state radio and television service, Radio Télévision Guinéenne. The Guinean government refers to the area as “le centre directionnel de Koloma,” which it plans to redevelop. A large sign in Conakry’s town center offers a futuristic vision of a new Koloma, which the sign refers to as, “the face of a developing Guinea.”

Prior to the evictions, the area was a mix of businesses, particularly car repair garages, and residential buildings, with concrete housing and some multilevel residences mixed in with some informal dwellings made from wood, corrugated metal, and other material. A prior round of demolitions, in 1998, had destroyed a smaller part of the area.

On February 2, the minister of towns and planning, Ibrahima Kourouma, stated that “illegal occupants” of Koloma had 72 hours to leave the area. On February 19, residents said that government officials and law enforcement placed red crosses on buildings, indicating those marked for demolition. The first demolitions began several days later.

Between February 22 and March 26, when the last demolitions occurred, the Association for those Evicted from Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, and Dimesse, a victims’ group, said that 19,219 people were displaced. Mohamed Mahama Camara, secretary-general of the Ministry of Towns and Planning, told Human Rights Watch that he did not believe this figure, and said that no more than 100 families had returned to Koloma after the earlier 1998 evictions. Satellite imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch, indicates that at least 2,500 buildings were destroyed in Koloma during the 2019 demolitions, suggesting that thousands of people were impacted.

Anger at the evictions on several occasions led young people from the neighborhoods to organize street protests. Guinean gendarmes and police fired teargas to break up protests and, residents alleged, to clear people from areas that were to be, or had been, demolished. Two witnesses said that, on March 14, a 14-year-old girl was hit in the face and seriously injured by a teargas canister fired by gendarmes. The government said that protesters were violent and threw stones at law enforcement.

To justify the evictions, Camara cited a 1989 decree that designated the Koloma area as government land. He said that those living on the land were “squatters,” who were living there illegally. Many of the victims interviewed said, however, that they had documentation showing that their families had acquired the land legitimately before the 1989 decree, such as evidence of government land grants or papers showing that they had bought the land from families with traditional or customary rights. “My family moved in during 1982,” said one resident, who said he had a legal document showing that the state had granted a plot of land to his father, a civil servant. The 1989 decree states that “occupants who developed their land before April 20, 1988 will not be evicted unless they are rehoused and compensated for the value of their assets.”

A group of residents from Kipé 2 filed a lawsuit challenging the legality of the evictions in 2018, after bailiffs had visited the area to inform occupants that they were living on state land and were required to leave. A first instance court ruled against them on March 1, but the case was appealed the same day. The appeal was pending when demolitions began in the Kipé 2 area on March 12. International standards require that affected residents be given the opportunity to challenge eviction decisions through judicial review.

Evictions in Dar Es Salam

The demolitions in Dar Es Salam occurred near Conakry’s largest garbage dump where, in August 2017, nine people died when a landslide stemming from nearby piles of trash covered several houses. Residents said that the government had since November 2017 warned more than 200 families living close to the garage dump that they would be subject to eviction.

Despite the proximity to the garbage site, the neighborhood where evictions occurred was largely made up of family houses made of stone and brick, some of them multilevel. Several of the residents said that their families have lived in the area for decades, often before the site began to be used as a garbage dump. “I’ve lived here for 43 years,” said one 60-year old resident. “My family bought the land from one of the area’s original inhabitants.”

On May 23, heavy machinery began demolitions in the area, with residents saying they received only a few days’ warning that demolitions were to start. Local people sought to prevent the demolitions but were eventually repulsed by a law enforcement response that, witnesses said, included helicopters flying overhead, dozens of gendarmes, and teargas. At least one person was injured by stray bullets fired during clashes between residents and the security forces. The towns and planning ministry said it warned residents to leave the site on multiple occasions and, when they refused to do so, it was necessary to use coercive measures.

By the afternoon of May 24, the first phase of demolitions, targeting houses whose residents had been warned about evictions in 2017, was complete. Later that day, witnesses said, government officials, protected by a cordon of gendarmes, placed red crosses on other houses in the area whose inhabitants had not previously been warned about evictions. Residents said they were given 72 hours to remove their belongings. These houses, witnesses said, were demolished on May 27. “They told us on Friday our homes would be targeted, and by Monday everything was destroyed,” said a Dar-Es-Salam resident. “How can that happen?”

Satellite imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch shows that at least 386 buildings were destroyed in Dar Es Salam in the May demolitions.

No Alternative Housing

Respect for the right to adequate housing is protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Guinea ratified in 1978. The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which monitors the covenant’s implementation, has said that governments must take “all appropriate measures, to the maximum of its available resources, to ensure that adequate alternative housing” is available after evictions. The United Nations Basic-Principles and Guidelines on Development-Based Evictions and Displacement make clear that safeguards against forced evictions, including the right to alternative housing, apply “irrespective of whether [those evicted] hold title to home and property under domestic law.”

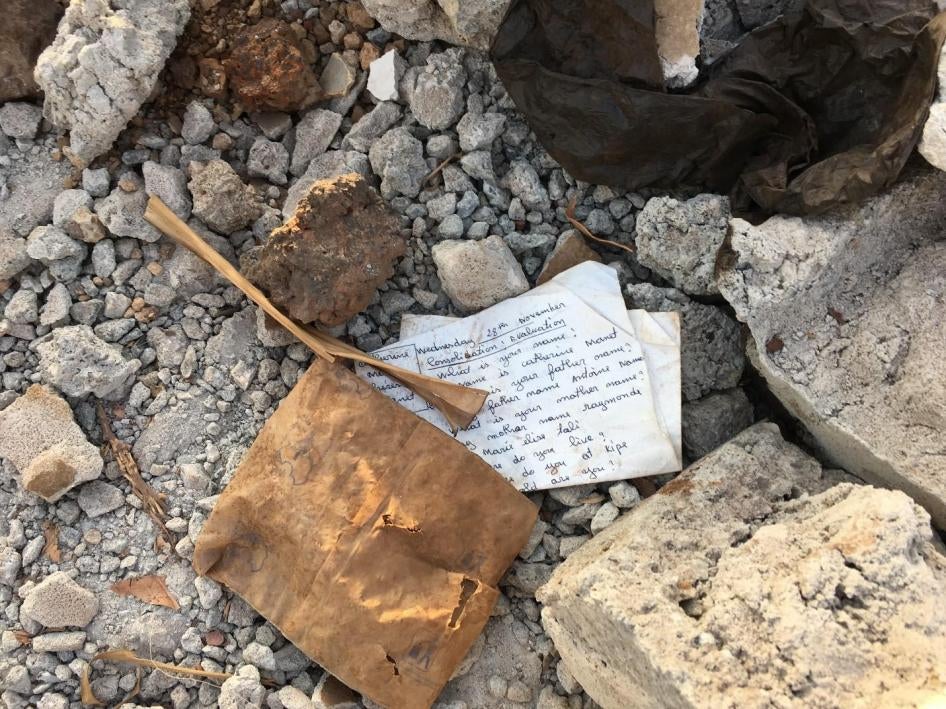

Residents of Koloma and Dar Es Salam said that, while they knew that the government was seeking to remove them, the lack of notice about when demolitions would start, the speed with which they occurred, and the government’s failure to provide any assistance left many people homeless. “We spent five days sleeping under a tree near our demolished house, with mosquito nets for the children,” said Onivogui Sayon, who lived in Kipé 2 with his wife and two children. “We finally found some friends to take us in.”

The United Nations Basic-Principles and Guidelines on Development-Based Evictions and Displacement require governments to resettle families or to ensure that they have access to alternative accommodation before evictions begin. “If they had at least given us a month, we could have found somewhere to live,” said Amadou Saikou Diallo, a Kaporo-Rails resident. Several weeks after the evictions, Diallo said he was moving from one friend’s house to another to sleep at night. “I keep my clothes, shoes, and toiletries in my backpack,” he said.

In a speech to residents of Kaporo-Rails in 2016, President Condé promised that the government would respect residents’ rights and provide alternative accommodation in case of evictions. “We are not going to throw people in the street,” he said. So far, however, the government has provided no alternative housing to those evicted, even to vulnerable families unable to find adequate accommodation on their own.

Camara, the towns and planning ministry secretary general, said that many of the evicted residents had other homes or properties that they could live in. He also said that, if needed, they could find accommodation with family members. “These evictions haven’t made anyone homeless,” he said. But weeks after the evictions, several people interviewed were still living close to the ruins of their former home. Some took refuge under shelters hastily constructed from scavenged wood, while others lived in nearby schools or mosques. “I have to live outside with my elderly mother and wife,” said Oumar Bar, who previously shared a house with his two brothers and their families. “I’m scared because with no electricity there’s no light at night and no security.”

An elderly widow in Dar Es Salam showed Human Rights Watch the temporary wooden structure where she lives, next to the ruins of her house. She shares the hut, which only has a wall on one side, with some of her children and grandchildren, the youngest an 8-month old baby. “Our homes were destroyed during Ramadam,” she said. ‘We have nowhere else to go.”

Although many residents have found alternative housing, they have often had to split up their immediate family, move to other neighborhoods, or leave Conakry. “To separate a mother from her children is a horrible thing,” said Makia Touré, a widow who is now living with an uncle, 50 kilometers away. Her six children, three of whom are 10 or under, are spread out among her relatives so that they can remain close to their schools. She worries that, as a widow and single parent, she won’t be able to afford another home. “The house we owned was the only way for me to live, because we didn’t pay rent,” she said.

Moving away has also forced some children to find new schools or stop their education. “My brothers and sisters are all at home now,” said Thierno Ibrahima Diallo, who has two 8-year-old siblings and another who is 4. “We’re living in Coyah, and it’s too far from their old school.” Another resident has moved his children to Boké, a town 250 kilometers from Conakry. His oldest child, an 8-year-old girl, has left her school in Conakry. “She’ll start school again next year,” he said.

Some residents feared that the profound trauma caused to children who saw their homes destroyed in front of them would have a lasting psychological impact. “We spent our whole childhood here,” said Diallo. “We grew up with neighborhood elders, going to the same cultural events. I felt like we were all from the same family. And now they’ve destroyed everything.”

Lack of Compensation

The vast majority of the evicted residents interviewed said that they had not received any compensation from the government. “We’ve received no compensation or humanitarian assistance,” said Adama Haura Barry, a Kipé 2 resident. None of the evicted residents interviewed in Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, and Dimesse had received any compensation. In Dar Es Salam, the government offered a portion of those evicted a lump sum of 20 million GF ($2,190), which several people said fell far below the value of their property. Residents said any compensation payments should be based on an assessment of the actual value of their land and homes.

Camara said that those evicted did not have a right to compensation because they were occupying the land illegally. He also said that some households had received compensation in past eviction operations and had simply reoccupied the land. Condé reportedly said on April 25 that “only people holding land titles that have been properly authenticated have the right to compensation from the State.”

Residents, however, said that the government should at least consider households’ claim to have longstanding property rights, supported by documentation, before determining whether to award compensation. “A blanket refusal to consider compensation means that the government is flouting victims’ rights,” said Mamadou Samba Sow, the spokesperson for a victims’ group.

International standards also make clear that the government should provide some form of compensation even to occupants without legally-recognized property rights. The United Nations Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development-based Evictions and Displacement state that:

All those evicted, irrespective of whether they hold title to their property, should be entitled to compensation for the loss, salvage and transport of their properties affected, including the original dwelling and land lost or damaged in the process. Consideration of the circumstances of each case shall allow for the provision of compensation for losses related to informal property, such as slum dwellings.

Government officials said that those evicted had the right to seek compensation by filing a legal complaint. Several residents said, however, that they did not believe that the Guinean justice system, which has a history of corruption and political interference, provided a fair and independent system for seeking compensation. On June 3, the Association for those Evicted from Kaporo-Rails, Kipé 2, and Dimesse filed a complaint to the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), asking the government to restitute lost land, provide the compensation needed to reconstruct homes, and pay additional damages.

To respond to the impact of the evictions, the Ministry of Towns and Planning should:

- Take steps to immediately establish an independent and fair system to assess claims and promptly and fairly award appropriate compensation, based on a household-by-household assessment of property rights and the value of their assets;

- Provide alternative housing to any residents who have not been able to find adequate housing of their own;

- Halt any further evictions until it can guarantee respect for the rights of residents, including adequate notice, and compensation and resettlement prior to evictions.