I was a year old when the Tiananmen Square massacre happened. I didn't know about the event that changed the course of my country's history until after I graduated from high school and learned what took place by chance on what was then a less-censored Internet. It took me several more years to understand the context and significance of the Tiananmen movement and the government's response.

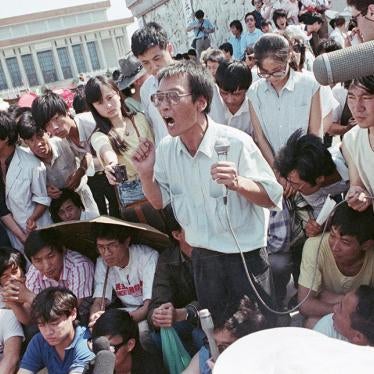

As I began to learn more about what happened, I became fascinated with photos of the student protests before the crackdown. In one picture, two students camping on the square pass the time dancing. Another photo shows a young man, fist raised, with an English phrase scrawled on his T-shirt: “My life is yours, my love is yours.” Then there is the photo of Liu Xiaobo, the future Nobel laureate who died in 2017, holding a megaphone as he gives an impassioned speech to the demonstrators.

The images of young men and women with unjaded, determined faces captured the aspirations of people across China and their belief in the possibility of transformative change — hopes that would no doubt resonate today.

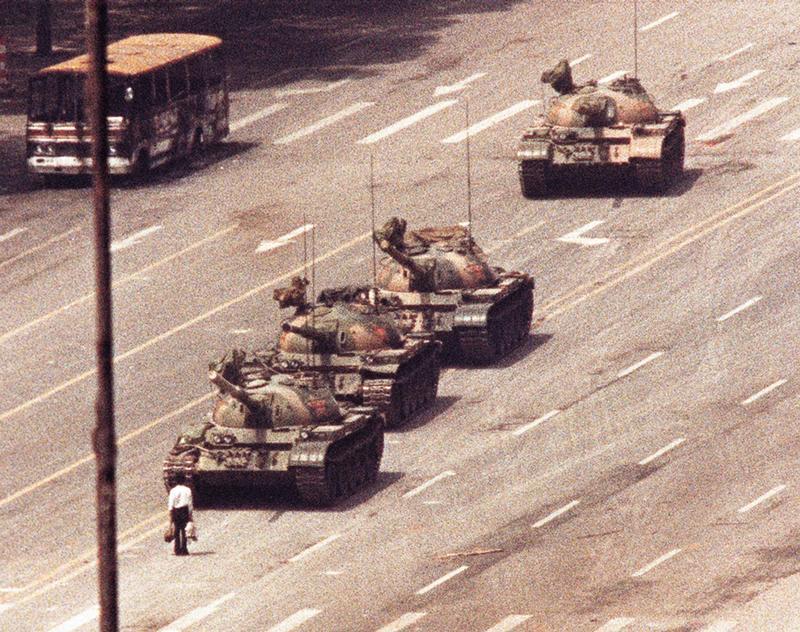

But thanks to unrelenting censorship, most Chinese of my generation have not seen these images. In 2014, journalist Louisa Lim found that only 15 out of 100students at four of China’s top universities were able to identify the iconic Tank Man photo. “Is it Kosovo?” one student asked. Among those who have heard about it, few know the scale of the protests and the magnitude of the ensuing brutality.

Today, the values the protesters aspired to then seem to be further away than ever. The Chinese government’s assault on human rights is at its worst since Tiananmen. In recent years, the Communist Party has stepped up arbitrarily detaining activists, lawyers and writers; assiduously deleting social media accounts and posts, and forcing people to memorize banal slogans professing their love for President Xi Jinping. In Xinjiang, the authorities are holding an estimated 1 million Muslims in political education camps to compel them to stop speaking their mother tongue, celebrating their holidays and practicing their religion. The state’s high-tech tools for mass surveillance now include facial recognition software that can even monitor people’s emotions — there can be a price to pay just for looking unhappy.

My generation has grown up in the shadow of these abuses. Some observers have confused our lack of Tiananmen-style demonstrations or other forms of activism with apathy or unilateral support for the government. But just because people aren’t speaking out publicly doesn’t mean they don’t have dissenting views.

Several years ago, when censorship was not as tight as it is now, millions of people — many my age — used social media every day to discuss political and social issues and to pressure local officials to right wrongs, prompting the widely known slogan, “changing China through collective spectating.” Even today, many young people are taking great risks to spread ideas and criticize and mock our leaders online.

Though censorship has left many Chinese of my generation in the dark about Tiananmen Square and other political issues, rapid economic growth has at the same time brought previously unimaginable opportunities — many of us have grown up in material comfort and have traveled and studied abroad. Through education, the Internet and our engagement with the outside world, we know that we are entitled to certain rights and freedoms.

This has also given rise to a new generation of human rights activists who are tech-savvy and connected to the international human rights movement. Even under tight government control, the new generation of women’s rights activists was able to set in motion the #MeToo movement in China, and young student and labor activists have brought factory workers’ suffering to the world’s attention. Many others are working under the radar, trying to build tolerance in society by advocating for the rights of children with disabilities and by spreading awareness of LGBTQ issues.

History shows that it is very hard to kill people’s spirit. The Tiananmen Square protests were one of the many efforts by people over more than a century to bring democracy and respect for rights to China. The current wave of repression is just one cycle in this long and continuing historical struggle.

Though we are living in a grim period for Chinese human rights, there is reason to hope. If more people of my generation and future generations have the opportunity to see the Tiananmen photos, they, too, will be inspired.

The Tiananmen Square protests were the embodiment of activists’ enduring love for the country — and the risks they are willing to take to see it change.