One year ago this month, Dr. Abiy Ahmed was sworn in as prime minister of Ethiopia. His first few months in office saw many positive human rights reforms and a renewed sense of optimism following several years of protests and instability, along with decades of repressive authoritarian rule. Thousands of political prisoners have been released, a peace agreement has been signed with neighboring Eritrea, and Abiy has pledged to reform repressive laws. But in the months that followed, growing tensions and conflicts, largely along ethnic lines, have resulted in significant displacement and a breakdown in law and order across much of the country, threatening progress on key reforms.

This week we will publish a series of assessments of Prime Minister Abiy’s first year in office, looking at his government’s performance regarding eight key human rights priorities and providing recommendations on what more needs to be done in his second year in office, leading up to elections scheduled for May 2020.

Today, in Part 4 of 8, we look at the government’s performance on Arbitrary Detention, Torture and Detention Conditions.

Arbitrary Detention, Torture and Detention Conditions

Progress has been made toward eliminating the longstanding practice of torture in Ethiopian detention but not enough has been done to hold those responsible to account and to investigate past crimes. The government has acknowledged that torture occurred in the past, a positive step, and it has closed some abusive detention facilities. The use of arbitrary detention as a tactic to stifle dissent or opposition to the government has decreased but is still a concern. Human Rights Watch has received fewer reports of torture and ill-treatment than previously.

Background

Torture has long been a serious and underreported problem across Ethiopia. For years, Human Rights Watch received frequent reports of torture in places of detention country-wide. These included police stations, prisons, military camps, and various unmarked detention sites. Other nongovernmental organizations and various media outlets have also reported on torture over many years. Some of the most brutal torture has occurred at the hands of the Ethiopian military and, since 2010, in the Somali Region, at the hands of the Liyu police.

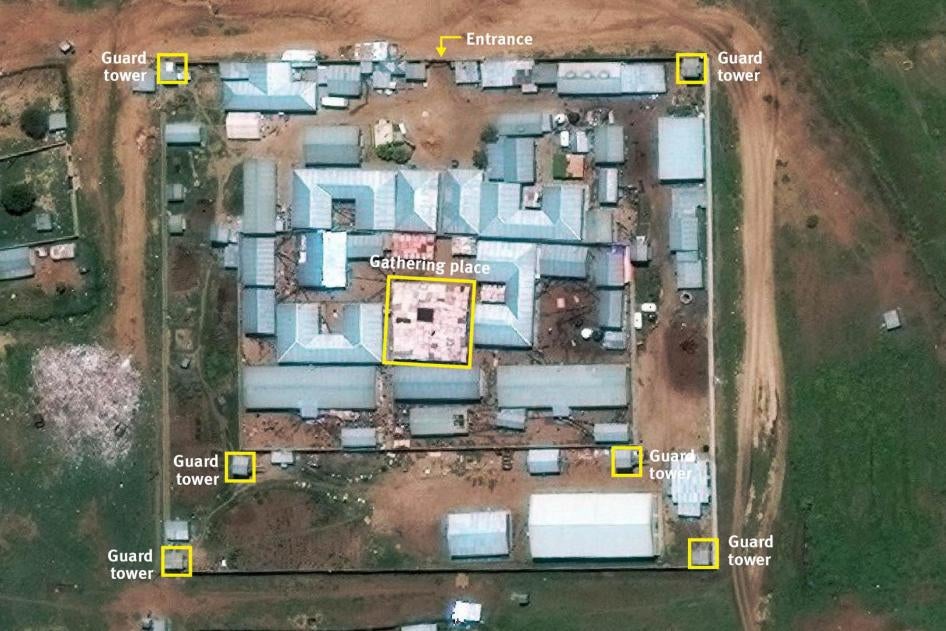

Torture occurred in facilities under federal, regional and local jurisdictions. For example, in Jijiga Central Prison, commonly known as Jail Ogaden, a regional detention facility in the Somali Region, prisoners were brutally and relentlessly tortured and humiliated individually and in groups. Many of them were accused of belonging to the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), a group banned by the Ethiopian government.

While patterns varied across the country, Ethiopian officials have often relied on torture to extract confessions, typically regarding a prisoner’s connection to one of the groups that the government had designated a terrorist organization, to gain information, or merely as punishment.

Prisoners in some detention centers had little access to medical care, family, lawyers, or even at times to food. Overcrowding has been a problem in some places of detention.

The government’s response to the allegations of torture was blanket denial, and to suggest that the allegations were politically motivated. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any cases in which the government held anyone to account for involvement in torture. The courts have routinely ignored complaints about torture. The government restricted independent monitoring of detention facilities by humanitarian actors. There were no viable systems for redress for torture.

Arbitrary detention has also been a significant problem in Ethiopia, with tens of thousands of people held without charge, sometimes for years, on suspicion of involvement with opposition parties or other opposition activity. Some people have been held in military camps. In some cases, large numbers of people were rounded up and sent to “rehabilitation camps,” where detainees were indoctrinated in government policies and perspectives, often forced to do strenuous exercises, and then released without charge. This approach was last used on a large scale during the 2017 state of emergency.

Under Abiy

Abiy and other senior officials have admitted that torture had been used, and some detention centers long associated with abuse were closed, including Jail Ogaden. Maekelawi was closed on April 3 following an earlier announcement. Most prisoners were released from Jail Ogaden. State run television ran documentaries describing torture methods used in Ethiopia. Some senior officials implicated in human rights abuses have been arrested, but very few security officials have been held to account for years of abuse and torture. Survivors of torture report that they are unable to access any of the psychosocial – mental health -- services they need.

Tens of thousands of political prisoners, including very high-profile prisoners, have been released from detention and many were pardoned. While there have been fewer reports of arbitrary arrests, there have been a number of arrests in areas of Oromia where there have been conflicts between suspected OLF members and the military. In September, 3,000 youth were detained around Addis Ababa. Some of them ended up in “rehabilitation camps” although conditions in the camps were reportedly not as harsh as detainees have previously endured. There have been some reports of politically motivated arrests in other parts of Ethiopia, but far fewer than in the past. While Human Rights Watch continues to receive some reports of beatings and mistreatment of detainees arrested in the past year, the volume has dropped dramatically.

As some steps have been taken toward increasing the independence of the judiciary, Human Rights Watch has begun receiving reports of detainees being asked by judges about how they are treated in detention – which generally did not happen in the past.

What more needs to be done

Abiy should publicly acknowledge the suffering of torture victims and take steps to improve the psychosocial services available for torture survivors and their families.

The government needs to hold people responsible for carrying out or directing acts of torture, regardless of their rank or political position, in fair, transparent trials, including those responsible for abuses in Jail Ogaden and Maekelawi. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and other independent observers, both international and domestic, should have access to federal and regional places of detention.

There has been more open dialogue about the existence of torture in Ethiopia. Ethiopia’s state broadcaster EBC even aired a documentary in December detailing numerous methods of torture carried out by security services. But the authorities still need to encourage victims of abuse to come forward and to ensure justice for torture.

Affiliation with the OLF or other opposition groups should not be a reason for detention. Anyone detained should be charged within the specified time frame under Ethiopian law or released. Military or “rehabilitation camps” should not be used for detention, and Abiy should publicly state that “rehabilitation camps” are a thing of the past.

Authorities should also ensure that federal, regional and other security personnel receive appropriate training on interrogation practices that adhere to international human rights standards, and they should ensure appropriate funding, oversight, and regulations to improve detention conditions. The government should also offer a standing invitation to the UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.