(Nairobi) – The Kenyan police and the South Sudanese authorities should ensure effective, transparent, and impartial investigations into the enforced disappearance of two South Sudanese critics in Nairobi more than two years ago, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said today.

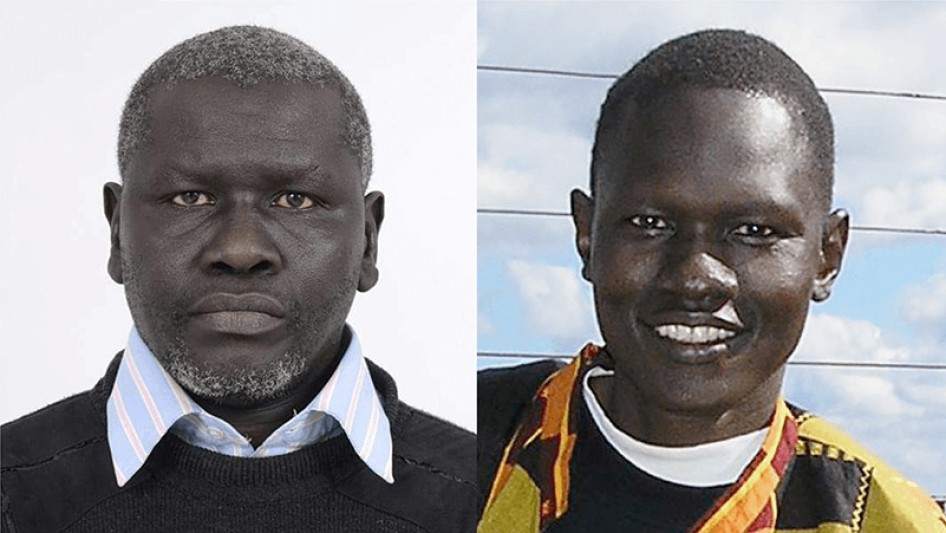

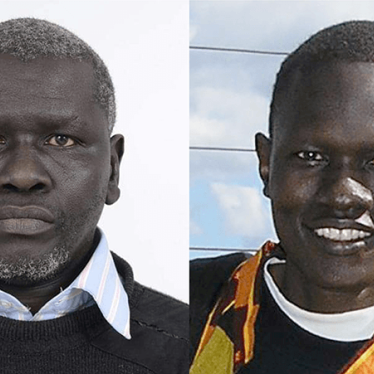

On January 17, 2019, a Kenyan High Court ended its 24-month oversight of the police investigation into the disappearances of Dong Samuel Luak, a prominent South Sudanese lawyer and human rights activist, and Aggrey Idri, a member of the political opposition. They were snatched off the streets of Nairobi on January 23 and 24, 2017, respectively. The families had initiated the petition for judicial review following concerns that the Kenyan police had not effectively investigated.

“The families of Dong Samuel Luak and Aggrey Ezbon Idri have waited patiently for the truth for two years, their lives in limbo,” said Jehanne Henry, associate Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “But this decision which lets Kenyan police off the hook, risks sending this case into oblivion and denying the families justice.”

The men’s disappearance is believed by their families and many who follow South Sudanese politics to be the result of collusion between South Sudan and Kenya, but both governments have denied having custody of the men or knowledge of their whereabouts. The Kenyan police have not officially requested information from the South Sudan government, nor has South Sudan’s government investigated the disappearances or officially requested information about the case from the Kenyan authorities.

Soon after the men were forcibly disappeared, their families filed a case before a Kenyan High Court seeking a writ of habeas corpus, to require the government to produce them in court. The court denied that petition, saying it could not establish that Luak and Idri were in custody but that a “criminal abduction by unknown persons” had taken place and that the police should thoroughly investigate the matter.

However, police investigations stalled. On April 20, 2017, the families sought judicial review and an order to the police to investigate the disappearance of the two men more thoroughly. In the following months, the court noted gaps in the police investigation, including the failure to seek information from the South Sudanese authorities and to interview witnesses and Kenya’s intelligence service. At a hearing on February 5, 2018, the police said they could not access some of the witnesses and they had no further leads but would keep the file open.

But the January 17 final judgement dismissing the petition stated that the police had acted “prudently and within the law.” The court said it is required to respect the police approach and timeline, and that families should pursue alternative administrative remedies such as filing a complaint with the Internal Police Oversight Authority. The decision ends any judicial oversight into the police action on the case.

“How long will this charade go on as the families of Luak and Idri continue to languish in agony over their loved ones?” said Joan Nyanyuki, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East Africa, the Horn and the Great Lakes.

Credible sources told both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International that they had seen both men in National Security Service (NSS) detention in Juba, South Sudan, on January 25 and 26, 2017. Information from South Sudan indicates that the men were moved from there on January 27 to an unknown location. Human rights organizations have documented the many serious human rights violations by NSS agents, including unlawful detention, ill-treatment, torture, and death in custody.

There have been more reports from former detainees corroborating that Dong and Aggrey were in South Sudanese custody in January 2017. In late 2018, a former detainee, William Endley, told the media that he had seen Aggrey and that others had confirmed seeing Dong at the prison in the NSS headquarters. But South Sudan’s government has remained silent and failed to investigate these reports.

If the two men are in the agency’s custody, as evidence strongly suggests, they are both at risk of abuse, including torture, the organizations said.

Dong was a registered refugee in Kenya, where he had lived since August 2013. Aggrey relocated to Kenya on a visitor’s pass after the conflict in South Sudan broke out in mid-December 2013 and was legally in the country at the time of his disappearance. Any acquiescence or cooperation by Kenyan authorities to the forced return of either man to South Sudan is a serious violation of Kenya’s international obligations.

This is not the first time that a South Sudanese refugee was forcibly disappeared from Kenyan territory, with the apparent agreement of the Kenyan government, and illegally returned to South Sudan. In December 2017, South Sudanese political opposition official, Marko Lokidor Lochapo, was forcibly disappeared from the Kakuma refugee camp. He was detained without charge in the notorious “Blue House” detention facility in Juba until October 25, 2018.

In November 2016, Kenya deported James Gatdet Dak, then the spokesman for South Sudan’s political opposition, to South Sudan under great protest. Gatdet was subsequently sentenced to death by hanging for treason but pardoned on October 31, 2018. Gatdet’s account of his illegal deportation confirms collaboration between the highest levels of the Kenyan and South Sudanese governments.

The South Sudanese government’s inaction and unwillingness to investigate the disappearances and the status and whereabouts of Dong and Aggrey is an abdication of its binding legal obligations, demonstrates total disregard for the men’s fundamental rights, and exacerbates their families’ concerns, the organizations said.

“My biggest fear is to become a widow,” said Aya Benjamin, Aggrey’s wife. “When I think about it, my heart hurts. We are limited in our daily lives and usual activities and I have become depressed. I am not as hopeful as I was two years ago.”

“Dong’s disappearance has psychologically affected all of us especially his four daughters. He is their best friend,” said Polit James, Dong’s younger brother. “The hardest question I face is ‘Where is daddy? When is he coming home?’ You sometimes find them crying and writing emotional letters in their notebooks.”