It is impossible to remain unmoved by the tragedy of Brumadinho: the sobbing families who await news about their missing loved ones, the bodies being pulled from the mud sea, the red slash of mine tailings spreading across the rolling green hills of Minas Gerais State. The avalanche of waste also laid bare the failings of the state.

Brazil has myriad environmental laws, empowering officials to regulate, monitor, and impose sanctions to activities posing environmental risks for Brazilians ranging from farmers and loggers to miners.

Yet the tragedies keep coming.

The collapse of the dam in Mariana in November 2015 took 19 lives and released millions of tons of poisonous sludge that reached the Atlantic Ocean, more than 300 miles away. That disaster pointed up the risks from many Brazilian dams that are holding back mining waste.

Brazilian authorities – from the Office of the Public Prosecutor to the federal, state and local institutions-- and the companies themselves should have made a commitment back then to a comprehensive evaluation of environmental compliance in the mining industry, with the aim of preventing future destruction and loss of life. But that didn’t happen.

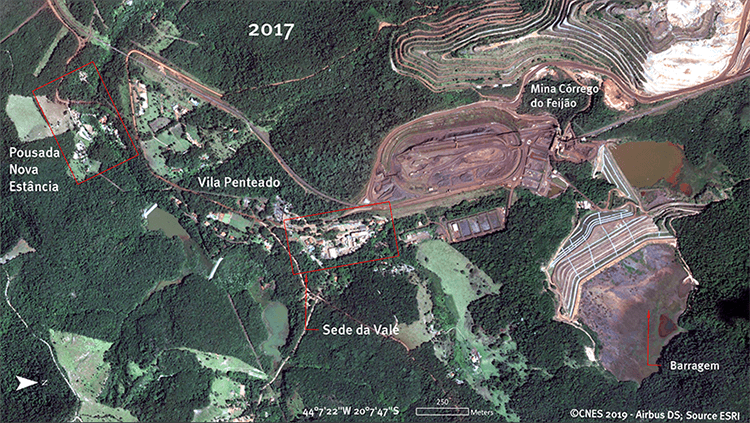

And so on January 25, when many employees at the Brumadinho dam had just sat down to eat lunch, a failing dam let loose a tidal wave of iron ore waste. The torrent swept them away.

In addition to 165 known dead, 160 people remain missing. The loss of life at Brumadinho is the stuff of nightmares.

Vale, the Brumadinho dam’s owner, was also a partner in operating the Mariana dam. Since that collapse in 2015, criminal and civil law suits have inched forward without reaching any conclusion. What hasn’t happened is what’s most needed—the government waking up to the urgent need for better monitoring and enforcement.

The National Water Agency, known by its Brazilian initials, ANA, reported last year that there are 24,092 dams registered in Brazil. It estimates, however, that there are at least three times as many other dams that are not registered, as required, with their monitoring agencies. Only three percent of the registered dams were inspected in 2017. ANA listed 45 dams considered at the highest risk of collapse.

Brumadinho was not even on that list.

While the government should have taken the lesson of Mariana and strengthened its environmental and regulatory framework to prevent other disasters, authorities at various levels were marching in the wrong direction. Shortly after Mariana, Minas Gerais passed a law loosening environmental licensing requirements for mining. And it is not just in mining. A bill pending in the National Congress would reduce oversight of hazardous pesticides used in farming. During last year’s campaign, President Jair Bolsonaro complained repeatedly that environmental licensing was getting in the way of development—and he has appointed officials who share that view.

After peering from a helicopter at the mud-slicked remains of Brumadinho, Bolsonaro promised to prevent further mining tragedies. We can only hope that, having witnessed the destruction, he’ll abandon backward-looking campaign promises.

It’s past time to beef up regulation, enforcement and monitoring. The government should act now to provide Brazilians with the protection they need from predictable disasters.