(Paris, June 15, 2017) – Equatorial Guinea’s mismanagement of its oil wealth has contributed to chronic underfunding of its public health and education systems in violation of its human rights obligations, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Declining oil reserves mean that there is very little time left for the government to correct course and significantly invest in improving the country’s woeful health and education indicators.

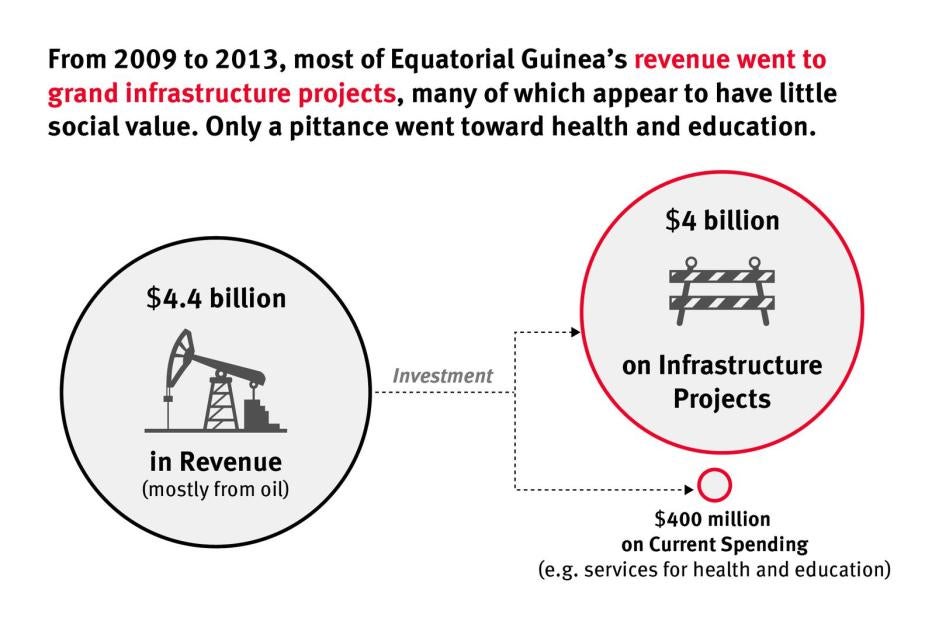

The 85-page report, “‘Manna From Heaven’?: How Health and Education Pay the Price for Self-Dealing in Equatorial Guinea,” reveals that the government spent only 2 to 3 percent of its annual budget on health and education in 2008 and 2011, the years for which data is available, while devoting around 80 percent to sometimes questionable large-scale infrastructure projects. The report also exposes how, according to evidence presented in money laundering investigations carried out by several countries, senior government officials reap enormous profits from public construction contracts awarded to companies they fully or partially own, in many cases in partnership with foreign companies, in an opaque and noncompetitive process.

“Ordinary people have paid the price for the ruling elite’s corruption,” said

Sarah Saadoun, business and human rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Now that the economy has been doubly hit by declining oil production and prices, it is more critical than ever for the government to invest public funds in social services instead of dubious infrastructure projects.”

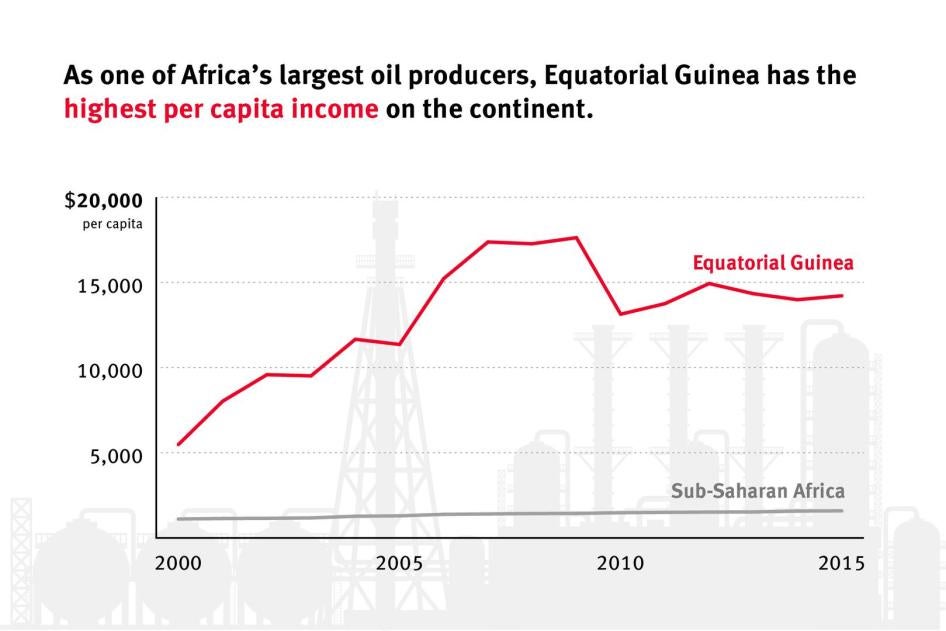

Equatorial Guinea, a small central African nation of around 1 million people, took in approximately US$45 billion in oil revenues between 2000 and 2013, catapulting it from one of the world’s poorest countries to the one with the highest per capita income on the African continent. But since 2012, its GDP has contracted by 29 percent and, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), oil reserves are expected to run dry by 2035 unless new ones are found.

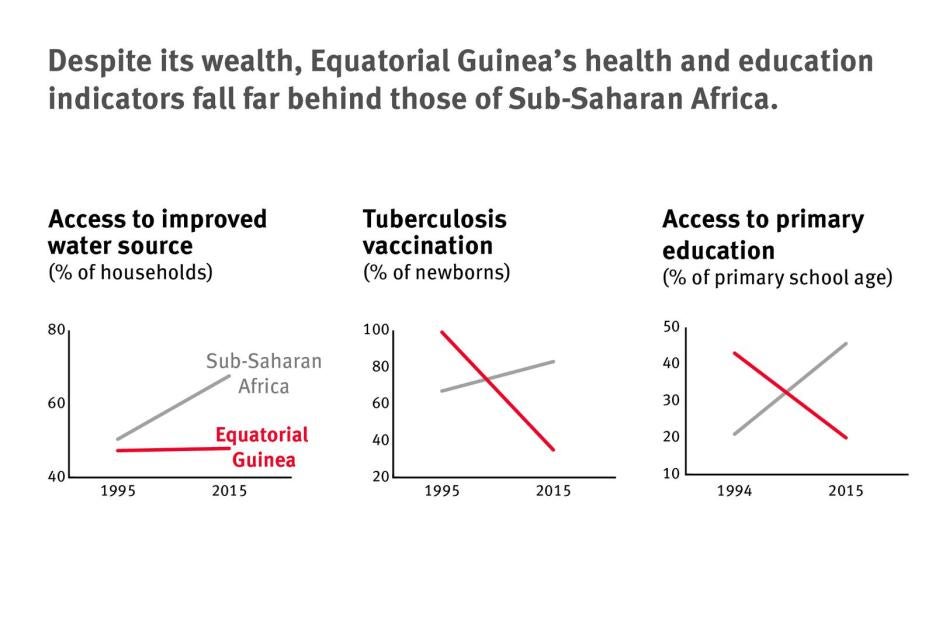

Teodoro Obiang has been president since he overthrew his uncle in 1979, making him the world’s longest-serving president. Despite its substantial wealth, the Obiang government has

largely squandered the opportunity to use its oil riches to transform the lives of ordinary citizens. Progress on health and education indicators lags regional achievements, and some have deteriorated since the start of the oil boom. For example, vaccination rates are now among the worst in the world, and tuberculosis vaccination for newborns and infants dropped from 99 percent in 1997, to 35 percent in 2015. More than half of Equatorial Guinea’s population lacks access to nearby safe drinking water, a rate that has not changed since 1995, and, in 2012, 42 percent of primary-school-age children – 46,000 children – were not in school, the seventh-highest rate in the world.

Yet the government spent only US$140 million on education and $92 million on health in 2011; and $60 million on education and $90 million on health in 2008, according to reports by the IMF and World Bank.

At the same time, government officials have built personal fortunes from the country’s oil wealth. The United States Department of Justice accused the president’s eldest son, Teodorin Obiang, of using his position as minister of agriculture to amass US$300 million – more than the combined health and education budget in some years. The president appointed Teodorin vice president in June 2016.

The US case was settled when Teodorin agreed to forfeit US$30 million in assets located in the US, but a French money-laundering investigation against him will go to trial on June 19, 2017. Prosecutors there allege that between 2004 and 2011, €110 million was transferred from the Public Treasury into Teodorin’s account, fueling a €175 million Parisian shopping spree on a mansion, luxury automobiles, and designer goods. In October 2016, Switzerland opened an investigation into Teodorin, seizing 11 luxury cars and a US$100 million yacht.

Since 2009, the government has spent virtually all its oil revenues on large-scale infrastructure projects. Evidence and interviews from investigations indicate that government officials frequently own stakes in companies that bid on public infrastructure projects. For example, businesspeople and IMF experts told US investigators that the presidential family owns stakes in several of the country’s largest construction firms. A US senate investigation and leaked State Department cable allege that the president at least partly owns the company with a monopoly on cement imports.

Obiang has defended his government’s high levels of infrastructure spending as necessary to modernize the country and its economy. But it appears that self-dealing frequently leads to inflated contract prices and approval for projects with little social value at the expense of crucial priorities including health and education services. Moreover, an opaque and noncompetitive procurement process generally makes it impossible to determine the amount and beneficiaries of public contracts.

In one stark example, the government is constructing a new administrative capital, Oyala, in the middle of the jungle after it spent hundreds of millions of dollars constructing government buildings in both the island capital, Malabo, and the largest city, Bata, for the same purpose. According to a 2015 IMF report, planned total spending on Oyala that year came to US$8 billion. An unpublished draft of a 2016 IMF report obtained by Human Rights Watch estimated that spending on Oyala would consume half of all public investment in 2016.

“While its oil reserves dry up, the government defends the status quo,” Saadoun said. “It may not be too late to put Equatorial Guinea’s oil wealth to good use, but the window is closing fast.”