Kenya will hold presidential and general elections in August. Campaigns are a difficult time for Kenyans, who may associate voting with tension and chaos. They keenly remember how 2007 post-election violence split groups down ethnic lines and left more than 1,000 people dead and hundreds of thousands displaced. Kenya’s media play a key role in reporting on election-related subjects critical to voters, like corruption, police brutality, and land acquisition. Yet Kenya’s journalists, already facing obstacles to their reporting, increasingly fear threats and physical attacks to silence them as the election nears. Kenya researcher Otsieno Namwaya speaks with Audrey Wabwire about the new Human Rights Watch report, “‘Not Worth the Risk’: Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections,” and what he learned, together with the media freedom group Article 19 Eastern Africa, when they talked to journalists and bloggers across the country.

How are journalists and bloggers being targeted in Kenya?

In recent years, the Kenyan government has been largely hostile to human rights issues. Civil society groups and the media have had little room to criticize the government without fear. Government officials have not been keen on protecting the rights of journalists and bloggers who write on issues of national importance. When President Uhuru Kenyatta took office in 2013, his administration moved quickly to pass very restrictive laws that negatively impacted media freedom. The Kenya Information and Communication (Amendment) Act and the Media Council of Kenya Act, both of 2013, for example, expanded the government’s control over media regulatory bodies such as the Communications Authority of Kenya, the Complaints Commission, and the Multimedia Appeals Tribunal.

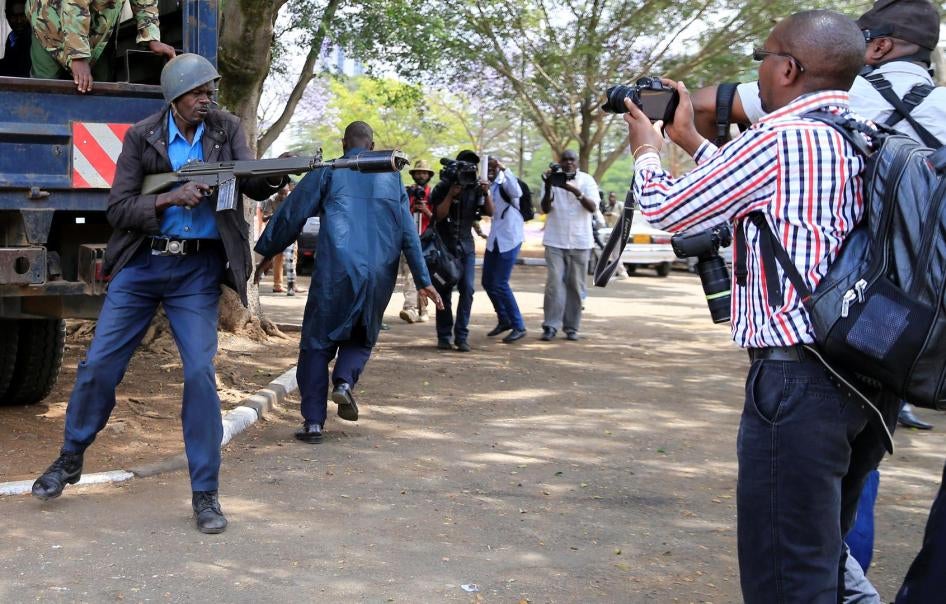

Officials have targeted journalists and bloggers over articles critical of government on issues like corruption, irregularities in land acquisition, accountability for political violence, or security force abuses. Those writing on these issues are either threatened and harassed – in some cases beaten – or subjected to online and phone surveillance. Journalists and bloggers are concerned that, as the elections draw closer, scrutiny of the media by the authorities and by those running for office will become more intense, with increased chances of abuse.

What struck you most as you conducted this research?

I was surprised that in some cases we documented of police officers beating journalists, the officers were not even worried about being held responsible. They went on discussing these beatings very openly. One such a case was the arbitrary arrest and detention and beating of the Standard newspaper journalist Isaiah Gwengi of Siaya county, western Kenya.

I spoke to Gwengi, who is in his early 30s, in detail about what happened. In brief, Gwengi wrote regularly about abuses by the Quick Response Team (QRT) unit of the Administration Police, one of the two branches of Kenya’s police force. Gwengi said his stories alleged QRT’s involvement in illegal charcoal trading, brutality, extortion, and arbitrary arrests of villagers. He received threats from the officers each time his stories were published. He eventually told his supervisor, family, and human rights activists in Siaya that he was afraid.

On March 22, police officers arrested Gwengi, together with a human rights activist, Rodgers Ochieng, bundled them into a police vehicle, and drove to the station. The officers slapped, kicked, and gun-butted Gwengi and Ochieng on the way to the station. The officers also stripped Gwengi naked and humiliated him. When he protested, they kicked him in the stomach, back, and face. He was hit in the back and in the ribs with the butt of a gun. He bled profusely.

They beat him unconscious, later taking him to Usenge police station in Siaya county, then to a nearby hospital on the insistence of the station’s commander who became worried about both men’s condition. As the officers drove Gwengi and Ochieng back from the hospital later that night, the officers stopped the vehicle and openly argued about whether to throw the two into nearby Lake Victoria.

Gwengi and Ochieng were released the next morning following a public outcry online and in the village.

The fact that these officers were bold enough to do this in broad daylight, in police uniform, in police stations, using police vehicles, without worrying about the fact the two were arrested in full view of villagers, is shocking and it doesn’t bode well for other journalists seeking to bring police abuse to light. Clearly cases like Gwengi’s will cause other journalists to self-censor.

Kenya has suffered many attacks by Al-Shabab militants in recent years. Shouldn’t journalists be more careful when reporting on police abuses, as police are working to keep people safe?

National security interests and free expression are not mutually exclusive. Kenyan authorities rarely cite national security concerns when subjecting journalists and bloggers to arbitrary arrests, surveillance, and threats. And when Kenyan officials do cite national security, it is to prevent journalists and bloggers from asking probing questions about killings and enforced disappearances of suspects by police, corruption, or lack of accountability for abuses. When there is an Al-Shabab attack, Kenyans have a right to know what happened and what measures authorities have taken to prevent future attacks or address failings in security. However, Kenyan officials typically respond to horrific attacks by moving quickly to stop journalists and bloggers from writing about it, to keep information from reaching the public. This was the case with the attack on the Kenyan military camp in El Adde, Somalia, in January 2016. To date, the truth about the attack, including the number of Kenyan soldiers killed and wounded, is not public. The government should recognize that free expression is important for national security, not a hindrance to it.

How have police responded to attacks on journalists and bloggers?

In public, police would say investigations are “ongoing.” But our research shows that police rarely investigate abuses against journalists and bloggers. In one case in Eldoret town, Rift Valley, a police commander who attacked a journalist and broke his camera later apologized and compensated the journalist. But there was no real justice since the commander didn’t not face any consequences for beating the journalist.

We investigated 23 recent cases of physical attacks against journalists and bloggers and 16 cases of threats and intimidation, and found no evidence that police have meaningfully investigated or held to account those responsible. And there is a wide range of government officials who are implicated in these abuses – county government officials, politicians, and state security officers.

Kenya has previously faced post-election violence, some of which was blamed on media reports. Isn’t it fair that the government ensures that the media remain responsible to avoid election violence in 2017?

The report of the Kenyan Commission of Inquiry into Post-Election Violence said the 2007 violence stemmed from disputes over election results, historical injustices, and issues of exclusion from opportunities and resources by the government. I don’t see any problem with the media highlighting these underlying causes of violence in Kenya, however sensitive. The media should be free to report on sensitive subjects and inform voters about governance challenges.

It is true the media was blamed for some of the violence in 2007. In large part this was mostly spurred by politicians and government officials who don’t want these issues to be discussed or are uncomfortable with media scrutiny. They want to avoid probing questions on their performance or questions on rights abuses. But for Kenya’s democracy to operate in the best interests of the public, including in the run-up to the August election, the media needs to be able to report freely on the decisions made by key government officials and other public officers and by all political parties.

This interview has been edited and condensed.