Summary

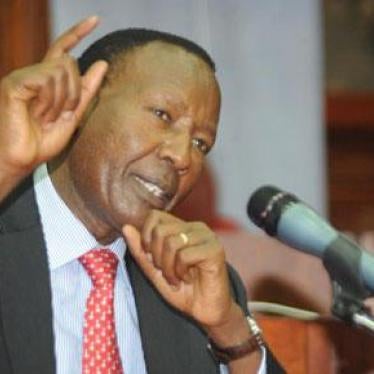

On November 3, 2015, Joseph Nkaissery, Kenya’s cabinet secretary for interior and national coordination, appeared before the Parliamentary Accounts Committee to answer questions about millions of dollars his ministry allegedly paid irregularly to suppliers, the bulk on the last day of the budget year.

Journalists from several Kenyan media outlets attended the session and published articles the following day. The fallout was swift. Nkaissery warned journalists who reported the proceedings they faced arrest if they failed to disclose their sources, and that leaking such information to the media could jeopardize national security. The minister either forgot or seemed to ignore the fact that the committee’s sessions were open, and journalists were present when members of parliament questioned him.

Soon after Nkaissery’s warning, police from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) attempted to summon journalists who wrote the stories for interrogation regarding their sources, but they did not comply. Days later, the police bundled the Daily Nation’s John Ngirachu, who was among those summoned, into an unmarked vehicle, and drove him to the DCI headquarters in Nairobi for interrogation. The police denied him access to a lawyer, but released him without charge after four hours.

The state-orchestrated intimidation of journalists after Nkaissery’s committee session is symptomatic of risks and challenges they have faced under President Uhuru Kenyatta, who took office in April 2013, and is seeking reelection in general elections scheduled for August 8, 2017. As the election nears, Kenyan government officials are increasingly scrutinizing media reporting and the impact it has on public perceptions of governance, health and education services, security, land rights, state management of public funds and the ongoing lack of accountability for the 2007 post-elections violence.

An independent media is crucial for Kenya’s ability to hold free and fair elections. But rather than protecting free expression and media rights – guaranteed by Kenya’s Constitution and international human rights law – Kenyan officials have responded to critical press coverage with harassment, threats, criminal charges, withholding of advertising revenue and even violence against journalists and media outlets.

Based on four months of research and interviews with journalists, editors, bloggers, human rights activists, and government officials throughout Kenya by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa (“ARTICLE 19”) ndash; the regional office that monitors and documents violations of freedom of expression – this report documents abuses by government officials and agents and other actors against journalists and bloggers in the run-up to the 2017 general election. It highlights the government’s failure to fulfill its constitutional and international human rights obligations to protect freedom of expression and media freedoms.

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 research found that local and international journalists and media outlets in Kenya have come under pressure since Kenyatta assumed office in 2013. The government has attempted to obstruct critical journalists with legal, administrative, and informal measures, including threats, intimidation, harassment, online and phone surveillance, and in some cases, physical assaults.

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 documented 17 separate incidents in which 23 journalists and bloggers were physically assaulted between 2013 and 2017 by government officials or individuals believed to be aligned to government officials; at least two died under circumstances that may have been related to their work. Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 further documented 16 incidents of direct death threats against journalists and bloggers across the country between 2013 and 2017. In addition, police arbitrarily arrested, detained, and later released at least 14 journalists and bloggers.

Despite receiving formal complaints from journalists, police have rarely investigated the attacks or threats. There is no evidence that any state actor has in the past five years been held accountable for threatening, intimidating, or physically attacking a journalist or blogger in Kenya.

Police have themselves been implicated in online surveillance and, at times, in directly threatening and physically attacking journalists. In some cases, police have arbitrarily arrested, intimidated, or harassed journalists, such as John Ngirachu. In 2015, Kenyan authorities threatened to ban two foreign journalists working for an international media outlet for reporting on alleged police death squads implicated in extrajudicial killings.

Senior editors of media outlets critical of the government say that authorities have called for specific journalists to be sacked. In some instances, the authorities have withdrawn or withheld advertising revenue, demanding apologies for specific editorial content, or asked to tone down coverage of a range of politically sensitive topics, including land, corruption and security issues.

Kenyan authorities have often invoked alleged national security concerns as a basis to obstruct free expression and access to information, particularly as elections near. While national security can be a basis for limiting free expression under internationally-accepted principles, governments must use the least restrictive means possible in prohibiting such speech and the national security interests should be legitimate. Obstructing access to information regarding mismanagement of state funds, for example, is not a legitimate basis to restrict free expression.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Kenya is a party, provides for the right to hold opinions without interference and the right to free expression. The government harassment and intimidation of independent reporting, and lack of police investigations into such abuses, threaten to undermine Kenya’s 2017 elections. For free, fair, and credible elections to take place, the government should protect freedom of expression and work to ensure that no government or security official seeks to silence journalists or arbitrarily obstruct their access to information.

The government should respect and uphold its obligations under international human rights law, and voters’ right to receive and obtain information at this critical time.

Recommendations

To the President and Government of Kenya

- Publicly restate the government’s commitment to upholding freedom of expression and media freedom ahead of the 2017 elections.

- Publicly condemn physical attacks, killings, threats, harassment, obstruction, intimidation and arbitrary arrests of journalists and bloggers, and direct government officials and security forces to stop harassing threatening or physically attacking journalists and bloggers.

- Direct the inspector general of police to ensure prompt, thorough, independent and effective investigation of attacks, including the deaths of, and threats against, journalists and bloggers, and to adopt a plan that would address the failure to adequately investigate such cases.

- Ensure full respect for international law by allowing full, open reporting and commentary on any issues of pressing public interest, including security, corruption, and accountability for past election-related violence.

- Propose amendments to recent laws, such as aspects of Kenya Information and Communications Act, Media Council of Kenya Act and Security Laws Amendment Act, and administrative measures introduced since 2013 to bring them into line with Kenya’s obligations under international law regarding freedom of expression. Ensure that all laws enacted before the passage of the 2010 constitution such as the Official Secrets Act, Preservation of Public Security Act, and the penal code are amended or repealed to meet Kenya’s international legal obligations.

- Ensure all government agencies, including the Government Advertising Agency, do not use threats of loss of government-sponsored advertising in exchange for favorable coverage or as punishment for critical reporting.

- Ensure that officials, regardless of rank or position, who threaten, harass, or arbitrarily arrest individuals on the basis of unlawfully intercepted or acquired information are appropriately disciplined or prosecuted.

- Act to ensure that authorities investigate allegations of illegal surveillance by government officials as well as private actors.

- In advance of the 2017 elections, publicly respond to the 2015 request from the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression to visit Kenya.

To the Parliament of Kenya

- Amend the penal code, the Preservation of Public Order Act, the Official Secrets Act, the Prevention of Terrorism Act, and other laws to bring them into line with Kenya’s obligations under international law regarding freedom of expression.

- Review laws establishing all official media regulatory bodies, such as the Media Council of Kenya and Communications Authority, to ensure they can provide oversight free from government interference.

- Enact protections to the right to privacy to prevent abuse and arbitrary use of surveillance, national security, and law enforcement powers as guaranteed by international law applicable to Kenya. Ensure surveillance occurs only as provided by law, is necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate aim, and is subject to judicial and parliamentary oversight.

- Enact legislation to regulate the use of personal information that may be collected by state agencies and to guarantee the right of individuals to request any information the state may collect about them.

To the Inspector General of Police, National Police Service Commission, Independent Policing Oversight Authority

- Direct all police officers, particularly those attached to county offices, to ensure respect for media freedom.

- Investigate all reported cases of attacks, threats, and harassment of journalists and ensure those found responsible are appropriately held to account.

- Investigate police officers involved in intimidation, threats, arbitrary arrests, and physical attacks, targeting of journalists and bloggers, and appropriately refer cases for disciplinary measures or prosecution.

- Investigate any reported cases of officials, regardless of rank or position, threatening, harassing or arbitrarily arresting individuals based on unlawfully intercepted or acquired information, and appropriately discipline or prosecute those responsible.

To Political Party Officials

- Direct candidates not to interfere with the freedom of expression of candidates and parties, and respect everyone’s right to seek, receive and impart information and opinions, irrespective of political leanings.

To International Partners, including the United Nations, European Union and African Union

- Publicly speak about the importance of free expression and other fundamental freedoms associated with Kenya’s electoral process, and urge the Kenyan government to direct government officials not to harass or threaten journalists and bloggers.

- Enhance monitoring and reporting of media freedom violations related to the election and post-election period, particularly outside Nairobi.

- Call on the government to review all laws that impact media freedom, including regulatory institutions such as the Communications Authority of Kenya, to ensure they comply with Kenya’s human rights obligations.

- Support domestic nongovernmental organizations working to promote freedom of expression and other fundamental liberties in the context of the election.

To Kenya Union of Journalists, Bloggers’ Association of Kenya, and Other Journalist Groups

- Support education for journalists and bloggers on the right to freedom of expression and the Johannesburg Principles on National Security, and Freedom of Expression and Access to Information.

- Assist journalists and bloggers with information and skills on responding to security challenges and protecting themselves in the event of work-related threats, intimidation, arbitrary arrest, and physical attacks.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

ACHPR: African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

AP: Administration Police, one of two branches of National Police Service

CA: Communications Authority, state agency in charge of frequency allocation and regulation of the broadcasting sector

CA: Communications Authority of Kenya

CIPEV: Commission of Inquiry into the Post-Election Violence of 2007-2008

in Kenya

CORD:Coalition on Reforms and Democracy, a coalition of opposition parties in Kenya which was formed in advance of the 2013 elections.

COTU: Central Organization of Trade Union, the umbrella trade union in Kenya

CPJ: Committee to Protect Journalists

CS: Cabinet Secretary, the political head of a government ministry

DCI: Directorate of Criminal Investigations, a criminal investigations unit within the regular police, one of two branches of the National Police Service

DPP: Director of Public Prosecutions

ECK: Electoral Commission of Kenya, the former electoral management body disbanded after the 2007-2008 post-election violence

GAA: Government Advertising Agency, a state body created in 2014 to

centralize advertising

GSU: General Service Unit, a paramilitary unit within the police in charge of

riot control

ICC: International Criminal Court

ICCPR: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICT: Information, Communications and Technology

IEBC: Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, the national elections management body

IGP: Inspector General of Police

IPOA: Independent Policing Oversight Authority, a civilian police oversight body

K24: A television station owned by the family of President Kenyatta

KANU: Kenya African National Union, Kenya’s ruling party from 1963-2002

KBC: Kenya Broadcasting Corporation, the state broadcaster

KCA: Kenya Correspondents Association, journalists’ union representing all correspondents across the country

KDF: Kenya Defense Forces

KICA: Kenya Information and Communications Act

KTN: Kenya Television Network, owned by the family of ex-President Daniel Moi

KTS: Kenya Television Service, owned by Moi University in Eldoret

KUJ: Kenya Union of Journalists

MCA: Member of County Assembly

MCK: Media Council of Kenya

NASA: National Super Alliance, a coalition of opposition political parties created in January 2017, and fielding candidates in the August 2017 elections

NCIC: National Cohesion and Integration Commission, a statutory body created after the 2007-2008 post-election violence to forge ethnic cohesion and curb hate speech

NMG: Nation Media Group

NPSC: National Police Service Commission

NTV: Nation Television, owned by Nation Media Group

SLAA: Security Laws (Amendment) Act, 2014

SLDF: Sabaot Land Defense Forces, a private militia in western Kenya that emerged in 2007 to fight for redress of land grievances in Mt. Elgon county

TJRC: Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, created after the 2007-2008 post-election violence

Methodology

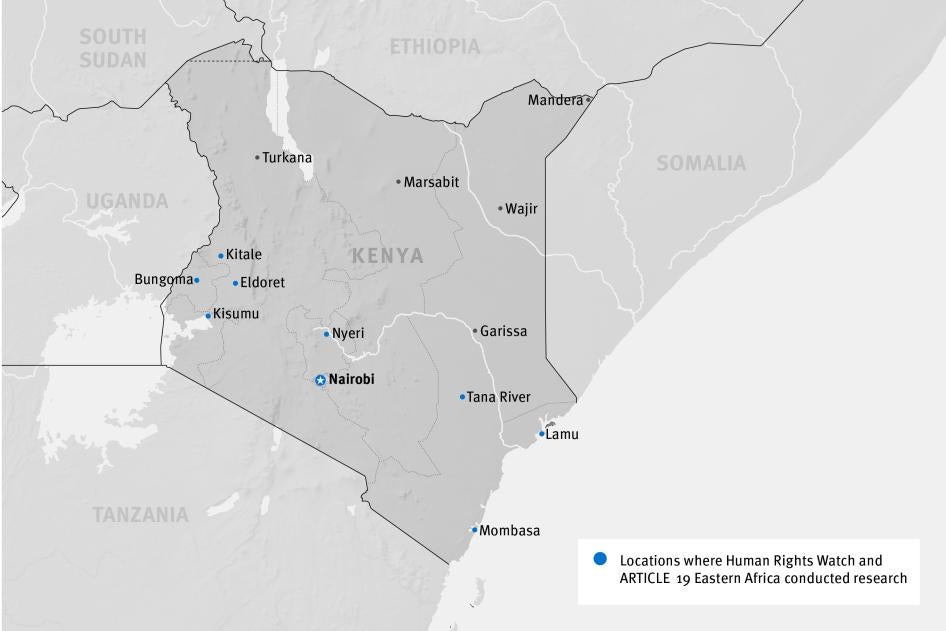

This report is based on research by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 in Nairobi, Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia, and Kisumu counties in Kenya between September 2016 and January 2017.

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 interviewed over 92 individuals, including 60 journalists, 10 bloggers, three lawyers specializing in free expression matters, two members of civil society organizations, three members of political parties, two senior journalists, police, and government officials in the Office of the President, Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology (ICT), and the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA).

Interviews were conducted with journalists and bloggers in the capital, Nairobi, where most of Kenya’s media organizations and journalists are concentrated, but also in other towns. In recent years, many FM radio stations have been established in many of the nation’s 47 counties, by politicians close to the current or former ruling parties. Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 interviewed journalists in Eldoret town in Uasin Gishu county, Kitale town in Trans Nzoia county, both in the Rift Valley, and Kisumu town in Kisumu county in western Kenya. We did additional telephone interviews with journalists based in Bungoma and Siaya counties in western Kenya, Elgeyo Marakwet and Nakuru counties in the Rift Valley, Mombasa and Lamu counties at the coast, and Nyeri county in central Kenya. These towns were selected for research to cover the geographic breadth of Kenya, and because each has a concentration of journalists and bloggers. In total, we spoke to 60 journalists and 10 bloggers in eleven of the 47 counties, four print media outlets, six television stations and three FM stations.

We interviewed journalists from print and electronic media, from both public and independent stations, but a large proportion of those interviewed work for independent newspapers and FM stations. We also interviewed bloggers and a few television journalists.

All interviews were conducted in English and typically lasted one hour and were all one-on-one interviews.

No compensation or any form of remuneration was given to any interviewee.

Many interviewees voiced concern for their safety or fear of possible loss of employment or business if authorities learned that they had spoken to a human rights organization. As a result, we have not disclosed their names and other identifying details.

On April 5, 2017, Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 shared initial research findings with the cabinet secretary in the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology, and the inspector general of police (see Appendix 2 and 3), requesting information on the wide range of human rights concerns contained in this report. We also requested for a meeting to discuss the findings. On April 27, the Inspector General of Police responded to our inquiries (see Appendix 6) but at time of writing we were still awaiting a response from the ICT cabinet secretary after he requested, via a telephone call to Human Rights Watch on May 2, 2017, more time to consult with the Attorney General.

On March 27, 2017, we shared our findings with the Aga Khan, the largest individual shareholder at Nation Media Group (NMG), regarding allegations of state pressure on its journalists (see Appendix 4). On April 13, 2017, we followed this up with another inquiry to the NMG chief executive (see Appendix 5). On April 24, 2017, the NMG chief executive officer responded saying he was not in a position to respond to our inquiries (see Appendix 7). At time of writing, the Aga Khan had not responded to our inquiries.

I. Background

Elections and the Media

Against the backdrop of the failure, by successive Kenyan governments, to address persistent long-standing and deep seated grievances by communities over land ownership and discrimination in accessing government services and opportunities which have caused divisions among communities since independence, Kenya is scheduled to hold general elections on August 8, 2017, as required under the 2010 constitution.[1] This will be the second under this constitution and since the controversial presidential election of December 27, 2007. The conflict that engulfed Kenya following those elections left over 1,000 dead and up to 500,000 internally displaced, marring the reputation of a country long viewed as a bastion of economic and political stability in a volatile region.[2]

In a political environment traditionally polarized along ethnic lines, general elections in Kenya have often been characterized by heightened tensions and competition among ethnic groups.[3] Kenyan journalists said the media must delicately navigate a fragile and often hostile environment while reporting on issues of national interest, such as security, land ownership, and corruption during the election period.[4]

Some editors pointed out that in December 2007, just before the then-electoral management body, the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK), declared the final presidential results, senior government officials summoned media managers and editors for an impromptu meeting in a bid to stop media organizations from broadcasting live, results from polling stations, in order for government to help prepare the public for the impending official announcement of the results.[5]

Shortly after the December 2007 meeting, all television stations, including the three leading independent stations – NTV, KTN, and Citizen TV – discontinued airing the tallying of presidential results from around the country.[6] Television stations also stopped live broadcast of the heated arguments between representatives of the opposition and ruling party at the tallying center in Nairobi, ostensibly about accuracy of the presidential results that were being announced.[7]

Since the violence surrounding the 2007 elections, government officials have frequently blamed the media for contributing to post-election violence, particularly by broadcasting live, the presidential election results, which government claimed raised questions about the reliability of the official results.[8]

A number of Kenyan politicians blamed the questioning of reliability of results – laid bare by the live broadcasts – for the ensuing inter-communal violence during which communities in rival political parties fought each other in the Rift Valley, Nyanza, Nairobi and at the coast. However, the commission that investigated the 2007 violence attributed it to numerous factors, including hate-filled and ethnically charged broadcasts by vernacular FM stations that capitalized on long-standing grievances by communities over land and discrimination in accessing government services and opportunities.[9] Radio journalist Joshua Sang was one of the six Kenyans who faced crimes against humanity charges at the International Criminal Court in The Hague for his alleged role in broadcasting hate messages.[10]

In the 2013 election, various state agencies and commissions focused on the role of media in averting the potential for violence and ensuring that rivals accepted the officially announced outcome of the elections.[11] As a result, the media did not have live broadcasts of presidential results from the polling centers – an apparent effort to avoid contributing to potential unrest, even if it meant underreporting alleged electoral malpractices.[12] In March 2017, the Communications Authority of Kenya announced it would not allow media outlets to live-broadcast presidential results from polling centers in the 2017 elections.[13]

Civic groups and the political opposition have criticized Kenyan media for sacrificing independence and freedom at the behest of government officials and peace campaigners.[14] In his acceptance speech soon after being declared winner of the March 2013 election, President Uhuru Kenyatta praised the press for being “patriotic” for not being critical of how the election was managed.[15]

Elections and Hate Speech in Kenya

Section 13 of Kenya’s National Cohesion and Integration Act defines hate speech, including publishing or using language that incites ethnic hatred. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) is the statutory body mandated to address hate speech and ethnic polarization by evaluating laws and policies for discrimination and promoting ethnic tolerance. Members of the public can submit complaints of ethnic or racial discrimination, and the commission can investigate and make recommendations to the attorney general and the Human Rights Commission for further action.[16]

In late March 2017, the NCIC announced plans to deploy 206 staff with surveillance equipment across the country,[17] to improve its capacity to monitor and investigate hate speech in political meetings, social and traditional media during an election cycle.

Many journalists and bloggers have raised concerns that government officials accuse the media of hate speech as a pretext to crack down on free expression.[18] Civil society organizations and opposition political parties have accused authorities of selectively applying Kenya’s law on hate speech to target writers critical of the government but ignoring similar content published by government-friendly writers.[19]

|

Ethnic-based attacks and reprisals that often appeared to be meticulously organized, as well as police use of excessive force, killed at least 1,100 people during Kenya’s 2007-2008 post-election violence, injured thousands more, and forced as many as 650,000 people from their homes.[20] Officials say there were at least 900 cases of sexual violence, but the actual figure is likely much higher.[21] On December 15, 2010, the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecution announced that it was seeking summonses on crimes against humanity charges for six people including now-President Kenyatta, and the current deputy president, William Ruto, for their alleged role in the violence.[22] Cases against only four of the six individuals were sent to trial, and, by 2015, charges against two of these, including President Kenyatta, had been withdrawn prior to trial, for lack of evidence. While short-cuts in ICC investigations may have been a factor, the Kenyan government also stoked hostility against the court, leading, in the prosecution’s view, to the withdrawal of a number of witnesses due to security concerns.[23] ICC judges also ruled that the government obstructed the prosecution’s investigation.[24] On April 5, 2016, ICC judges vacated crimes against humanity charges against Ruto and a former broadcaster, Joshua arap Sang, ending the last ICC prosecution directly related to the post-electoral violence.[25] Witness interference was a clear factor in compromising the Ruto and Sang trial. The prosecution claimed 16 of its witnesses withdrew, most citing threats, intimidation, or fear of reprisals.[26] A man claimed by Ruto’s defense as a witness was murdered in late December 2014 or early January 2015.[27] An ICC pretrial chamber issued arrest warrants for three people on charges of witness tampering in the case starting in August 2013.[28] An ICC statement described the witness tampering charges as stemming from an alleged “criminal scheme devised by a circle of officials within the Kenyan administration.”[29] Kenyan authorities have not surrendered the three men to the ICC. A legal challenge to one man’s surrender remains pending before the Kenyan Court of Appeals. Journalists and bloggers who reported on Kenyan ICC cases at the time or called for accountability for post-election violence faced threats and intimidation. A number of writers in Nairobi, Central Kenya, and the Rift Valley are known to have gone into temporary exile inside and outside Kenya due to threats relating to the ICC cases. At least one journalist in the Rift Valley who was reporting on the ICC cases, John Kituyi, was killed by unidentified gunmen in 2015.[30] One pro-government blogger, Bogonko Bosire, has been missing since 2013, days after a controversial Facebook post that was deemed to have exposed a witness that at that time was set to testify in the Kenyatta case.[31] At the same time, social media and blogs exposed people to threats by erroneously branding them witnesses for the ICC against Kenyatta and Ruto, and were also used to spread hostility toward human rights defenders perceived to support the ICC process. Even though the Kenyan authorities knew the identities of some of those behind the blogs, there were no apparent efforts to stop the threats. To date, there have been only a handful of convictions in Kenya’s courts for serious crimes related to the post-election violence. |

Media Ownership

While Kenya’s Information and Communications Act empowers the Communications Authority to either issue or deny frequencies to both individual and institutional applicants, it fails to provide clear safeguards against political favoritism in the allocation of frequencies, and the broadcasting sector has largely been dominated by individuals close to government.[32] This has negatively impacted media freedom and diversity of editorial content in the country.

Government-owned Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) – both radio and television – was the sole broadcaster until 1989 when then-President Daniel Moi and his political allies established the first private television station, Kenya Television Network (KTN), at a time when the government denied frequencies to other applicants for private television and radio stations.[33] The Ministry of Transport and Communications, which issued broadcasting licenses, and the then-Kenya Posts and Telecommunications, which officially allocated frequencies, both rarely provided reasons for denials.[34] It was not until 1995 that, in response to local and international concerns over media ownership environment, other independent broadcasters were allowed to begin setting up broadcast stations, particularly FM radio stations owned by individuals aligned to the then-government.[35] In 1998 the new Kenya Information and Communications Act (KICA) was adopted, [36] splitting the Kenya Posts and Telecommunications to create, among others, a communication agency, currently known as the Communications Authority of Kenya, to handle both the issuance of broadcasting licenses and frequency allocations.[37]

The government continues to maintain tight control over the allocation of radio and television frequencies.[38] Despite many television and radio outlets, the allocation of frequencies remains skewed in favor of individuals who are influential in the government or are sympathetic to it.[39] For example, Ali Chirau Mwakwere, whose family operates Kaya FM at the coast, and Koigi Wamwere, who owns Sauti Ya Mwananchi Radio and TV Ltd in the Rift Valley, acquired frequencies when they both served as ministers in the Mwai Kibaki government between 2003 and 2007. Samuel Poghisio, whose wife owns Elgonet Communication Technologies Ltd., which operates a radio station in the Rift Valley, acquired frequencies while he served as information and communications minister under Kibaki between 2007 and 2013.[40]

By October 2012, according to the Communications Authority, Kenya had 300 radio frequencies operational or on air.[41] Of these, the government-owned KBC was allocated 85 (22 percent) of the frequencies.[42]

Five big media groups own and operate the nation’s 22 television stations. The groups are KTN, owned by the family of former president Moi; NTV, which is part of the Nation Media Group (NMG) of which the Aga Khan, the global spiritual leader of Shia Ismaili Muslims, is the largest individual shareholder[43]; the government-owned Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC); K24, owned by the family of President Kenyatta; and Citizen TV owned by Royal Media Services of Samuel K. Macharia, a businessman and politician who has in recent decades oscillated between supporting the government and the opposition.[44] All these five major television operators also operate radio stations with considerable geographic reach, which means that, unlike the other media houses, each of the five have countrywide coverage.

Although recent market surveys in Kenya show that radio has the largest audience across the country,[45] most FM radio stations generally reproduce content from newspapers and television. As such, most of the documented abuses in this report and more broadly involve newspaper and television journalists because they produce original content.

Print media in Kenya has for decades been dominated by the Daily Nation and its weekend editions, all owned by NMG of the Aga Khan and the Standard newspapers that is predominantly owned by the family of former president Moi, whose family has publicly expressed support for President Kenyatta.[46] The other two daily newspapers, The Star, owned by Radio Africa Group, closely associated with Kiprono Kitony, a relative of former President Moi, and The People, owned by the Kenyatta family, reach a small, mainly urban based, segment of newspaper readers.[47] All these newspapers are Nairobi-based with a print run of around 130,000 copies per day for the Daily Nation and its weekend editions, 80,000 for the Standard, 40,000 for Star and around 10,000 for The People.[48]

Kenya’s Media Regulatory Bodies

Print and broadcast media are subject to the Media Council Act, 2013, which established the Media Council of Kenya (MCK). The MCK is mandated to protect press freedom and independence and is the main regulator of the media sector.[49]

The Media Council Act, 2013, further established the Complaints Commission, which is operationally under the Media Council of Kenya.[50] While the Media Council Act establishes the Media Council of Kenya and a Complaints Commission, a body vested with powers to adjudicate in disputes between public, government and media, Kenyan authorities introduced provisions that subject media to tight executive control.

The act gives the cabinet secretary wide powers in appointing commission members, including the ability to select the panel to recruit council and commission members and to reject any names they forward to him for appointment. The government is the main financier of the MCK, which also has the mandate to enforce the journalism code of conduct.[51]

The body empowered to handle appeals from those dissatisfied with the commission’s decisions – the Multimedia Appeals Tribunal – is tightly controlled by the Communications Authority (CA), whose chairperson is appointed by the president.[52] Other board members include the principal secretaries of the ministries of finance, security, media/broadcasting matters and seven other people appointed by the cabinet secretary. Under KICA, the Communications Authority has the mandate to enforce the broadcasting code.

Journalists found guilty by either the Complaints Commission or the Appeals Tribunal for any of the offenses under Media Council Act and KICA could face six months in jail or fine of Kes200,000 (US$2,000) – Kes1 million (US$10,000); media outlets could pay up to US$20,000.[53] Although the law establishing Multimedia Appeals Tribunal was enacted in 2013, its establishment was held back until 2016 by a Kenya Union of Journalists’ petition challenging its constitutionality, which the union lost. It therefore has yet to hear any appeals against journalists or the media.

Print media is governed by the Books and Newspapers Act, which establishes the Office of the Registrar of Books and Newspapers in the Attorney General’s Office. New publications must seek registration from the Office of the Registrar of Books and Newspapers, deposit a cash bond of Kes1 million (US$10,000) and two copies of the new publication before they could be allowed to publish.[54]

Sensitive Subjects for Media

If you have written about security agencies or corruption-related stories, you have to know that you are being followed or your phone is being listened into.

—Nation Media Group reporter, Nairobi, December 2016

I no longer write stories relating to corruption or irregularities in the Land Ministry. It is not worth the risk.

—Standard reporter, Eldoret, January 2017

Many of the senior editors, journalists, and bloggers interviewed by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 said that since 2013 they no longer report freely on land issues and other subjects in which senior government officials and other influential individuals have an interest. Such issues include corruption in national and county governments; security-related matters; and the 2007-2008 post-election violence and lack of justice for victims in the Rift Valley and Central Kenya. They said they were concerned they could face increased threats or physical attacks for writing about these sensitive subjects in the pre-election period.[55]

Land

Owing to unresolved historical injustices, land ownership has traditionally been a sensitive subject in Kenya, especially during election periods.[56] Since independence, the family of President Kenyatta and other influential individuals in successive governments have traded accusations of irregular land acquisitions in the Rift Valley and the coast.[57] The 2015 Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) report documented injustices between communities across Kenya and linked incidents of election-related violence since 1992 to land-related grievances.[58] Land conflict was cited as one of the underlying causes of the 2007-2008 post-election violence when the Kalenjin and Kikuyu ethnic groups in the Rift Valley clashed over historical disagreements originating in the 1960s regarding government land allocation and lack of compensation to some communities.[59] During the 2013 election campaigns, then-Inspector General of Police David Kimaiyo barred politicians from discussing land ownership as a campaign subject because he argued it risked sparking ethnic violence.[60]

The administration of President Kenyatta has not implemented the TJRC’s far-reaching recommendations on land, including revocation and recovery of all irregularly and illegally acquired land since 1963.[61] According to a journalist working with a leading media outlet in Eldoret: “Since unknown people kidnapped me in 2015 for reporting on land, I decided never to write land related stories. It is not worth the risk.”[62]

Corruption

Civil society organizations and the political opposition have accused the Kenyatta administration of failing to act on rising reports of mismanagement of state funds and alleged corruption by government officials.[63] Since 2015, for example, Kenyan authorities have failed to explain the whereabouts of part of US$2.5 billion that accrued from the “Eurobond” sale scandal in 2014,[64] as well as to justify the tripling of the cost of construction of the Standard Gauge Railway line between Nairobi and Mombasa.[65] Allegations of unaddressed corruption in the Ministry of Health have also been at the heart of a labor dispute and ultimately, a three-month strike by Kenya’s doctors that began in December 2016.[66]

Many journalists and bloggers said that Kenyan authorities have tried to suppress media reporting on government corruption.[67] A senior editor with the Nation Media Group said at least four of its senior reporters writing on corruption issues had been targeted by state intelligence, which surveilled and monitored their calls and social media:

As a result of the surveillance, senior government officials officially complained to us in late 2015 that some of our journalists were working with the opposition to undermine the government with corruption stories. We had to let go of some of the journalists.[68]

Journalists and bloggers said that government officials routinely threaten those reporting on corruption and exerted pressure on media outlets to fire or find other ways of containing journalists reporting on corruption.[69] Senior editors said that Kenyan authorities believe that journalists and bloggers reporting on corruption are working for leading figures in the political opposition.[70]

Security and Counterterrorism

Discussing security and counterterrorism issues has been particularly sensitive in Kenya since 2011, when Kenyan troops entered Somalia in pursuit of the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab.[71] Opposition politicians have criticized the deployment. They question abuses by security forces and if the deployment is worth the lives of Kenyan soldiers lost in Somalia, and the killings of hundreds of Kenyan civilians in Al-Shabab reprisal attacks carried out in Kenya.[72] Government authorities have said that Kenyan troops will remain in Somalia until Al-Shabab is defeated.[73]

Journalists and bloggers writing about Al-Shabab attacks in various parts of Kenya and the government’s abusive response have been accused by senior government officials of being Al-Shabab sympathizers.[74] They have been threatened by police and other government officials, arrested and detained, sometimes without charge, and allegedly subjected to unlawful surveillance.[75] In December 2015, for example, the cabinet secretary for interior, Joseph Nkaissery, threatened to arrest journalists who reported about the alleged involvement of security forces in extrajudicial killings and mass graves in response to Al-Shabab attacks.[76] Nkaissery’s warning had a chilling effect on media investigations into the allegations and many questions regarding human rights abuses in the context of Kenya’s counterterrorism efforts remain unanswered.[77]

Political Parties

Senior editors said that journalists who regularly call leading opposition figures, even just as news sources, have been subjected to phone and online surveillance by the state, and that government communications and public relations officers regularly send money to journalists to encourage or reward positive coverage or agree to ignore negative stories.[78]

An editor with one leading Kenyan daily said that during the ruling Jubilee party delegates’ conference in Nairobi in September 2016, delegates “resorted to chaos to demand allowances that the party had promised them.”[79] Government officials asked him not to report the controversy on the front pages. He explained that one government communications officer transferred Kes20,000 (US$200) to his phone to thank him for downplaying the story by not running it as the main front page article. “I called him and politely declined to take the money … but this is what they always do with our journalists,” he said.[80]

Another journalist described how police interrogated him about his alleged association with opposition leaders and their spouses in early January 2016 and detained him for hours.[81] A broadcast journalist who in early 2016 was arrested, interrogated, and released without charge said:

Some of the questions I was asked had nothing to do with what I was arrested for, my post on social media. Police officers instead asked me about my tribe and how I am related to the opposition leader, Raila Odinga, and his wife.[82]

Journalists also said that leading opposition Cord party supporters physically attacked reporters working with K24, a station associated with President Kenyatta, in July 2016, injuring them and destroying their cameras.[83]

With heightened competition in the pre-election period, media outlets and journalists face pressure regarding how much prominence they give to stories that portray rival political parties positively.[84] Journalists and bloggers said that both the ruling party and the opposition have profiled journalists based on their ethnicity, their employers, and the nature of stories they write.[85] This means that journalists either have privileged access to certain politicians depending on their perceived political leaning, some of which is determined based on the ethnicity of individual journalists.[86]

County Governments

With the 2017 elections approaching, county governors and other locally elected leaders are keen to burnish their public image. Media reporting that negatively portray the governor or the county government can lead to problems for the journalists, according to some of the journalists interviewed for this report.[87]

The 2010 constitution divided Kenya into 47 counties and abolished the 8 administrative provinces that existed since independence in 1963.[88] Each county is headed by an elected governor who is mandated to appoint a cabinet that runs the county’s affairs.[89] Elected members of the county assembly (MCAs) debate and approve county budgets and bylaws and are meant to serve as the representatives of the county residents.[90]

One journalist said he had to stop covering functions of a senior county government official in the Rift Valley in early 2016 after the official persistently threatened he would either personally discipline the journalist or he would ensure his supporters did so over what the senior official perceived to be negative stories about the county.[91] In Trans Nzoia county, a journalist with a daily newspaper said hired individuals and county security guards attacked him in 2014 for reporting on a demonstration by county workers demanding better remuneration.[92]

Four journalists in Uasin Gishu county said that county government officials openly discriminate against non-local journalists whom they view as outsiders with no right to work there or write about the county.[93] A journalist with Kenya Television Service (KTS) said:

The governor … once tried to force me out of his function because I don’t come from his county. On the other hand, local journalists are reminded to be patriotic to the home county and not write negative reports. The county withholds adverts for any negative reports.[94]

A senior editor at the Standard newspaper described the county governments and governors as “vicious”:

Some of them have sent their militias to attack journalists. The most worrying thing is that police do nothing even when journalists report the attacks on them. Journalists can no longer criticize governors.[95]

Reporters and correspondents working in the eleven counties where we conducted interviews told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that senior county officials persistently accuse journalists of working against the county’s interests in exposing corruption or other malpractices there, and that journalists have faced threats and intimidation.

II. Abuses against Journalists

Killings and Other Assaults

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 documented 17 incidents in which 23 journalists and bloggers were physically assaulted between 2013 and 2017. In at least two of these incidents, journalists died in apparent work-related circumstances.

A family member said that, on April 30, 2015, unidentified assailants repeatedly hit John Kituyi, editor of the Eldoret-based Mirror Weekly, with blunt objects and killed him.[96] Former colleagues at the newspaper told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that at the time of his killing, Kituyi was investigating the killing of Meshack Yebei, whom William Ruto’s defense asserted was their witness.[97] Kituyi was also looking into allegations of tampering with witnesses in the ICC case against Deputy President William Ruto for alleged crimes against humanity during the 2007-2008 post-election violence.[98]

Kityui and some of his colleagues had been threatened over these investigations and colleagues said some of them had to leave town because the threats persisted even after Kityui’s death.[99] In July 2015, authorities arrested a serving military officer and charged him with Kityui’s murder and violent robbery. He was released on bond pending further police investigations.[100] Nearly two years later, the case is still pending in a court in Eldoret.

On September 7, 2016, unidentified assailants forced themselves into the house of photojournalist Denis Otieno in the town of Kitale, Rift Valley, and demanded photos in his camera before shooting him dead.[101] The photos were apparently ones that Otieno had taken of police officers shooting to death a motorcycle taxi rider at a Kitale bus station earlier in September. A family member said that before his murder, Otieno had expressed alarm about death threats.[102] No one had been arrested in relation to his killing at time of writing.

A Kitale journalist close to the Otieno family said: “The family recorded a statement with police. We all tried to give police information about the threats he had received and likely suspects. We have no evidence that anyone has been questioned by police. Investigations seem to have stalled.”[103]

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 documented several other incidents in which journalists were physically attacked apparently because of their work. A Standard newspaper journalist in Eldoret town said he was kidnapped outside his house on March 22, 2015 by people who questioned him about stories he had been writing about irregular land acquisitions by individuals in positions of influence.[104] He said:

The kidnappers asked me how much I earned at Standard newspaper to make me endanger my life by writing land stories. They questioned me over a range of land stories I had written but then zeroed in on Dagir Farm which has controversy between the owner and squatters and which is where some senior government officials are believed to be putting up multi-million shilling homes.[105]

The journalist said he was threatened, drugged, and discovered unconscious two days later more than 40 kilometers away.[106]

A Daily Nation newspaper journalist said he was kidnapped and detained in a secret cell at a Kisumu police station in 2015 by police officers who expressed anger about his stories exposing their alleged involvement in crime in western Kenya.[107]

In Kitale town, the northern Rift Valley, a reporter described a journalist who in 2015 moved away from Kitale and abandoned journalism after individuals linked to officials in the Kitale county government kidnapped and beat him allegedly because of stories he had written about labor rights demonstrations by county employees.[108] On March 22, 2017, in Siaya county, in western Kenya, officers from the Quick Response Team of the administration police allegedly arrested, assaulted and badly injured Standard newspaper journalist Isaiah Gwengi for what Gwengi and his bureau chief believe was related to his stories on police brutality, extortion and involvement in illegal charcoal business in the area.[109]

While local human rights groups have in some cases offered relocation support for journalists and bloggers, they have called on journalists’ unions to establish a special fund to assist freelance journalists in the counties address their protection needs.[110]

Police Involvement in Physical Attacks

Since, 2013, police, other government officials, and agents have been involved in at least 21 incidents of assaults and other abuses against journalists and bloggers documented by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 across Kenya.[111] There is no evidence that the attacks by police officers on journalists and bloggers reflect government policy, though in several instances they appeared to be acting on the instructions of others. In general, officers seemed emboldened by the hostility of senior government officials to the media, the dysfunction of the National Police Service’s internal accountability mechanism, and the widespread impunity enjoyed by police officers who commit abuses.

On April 17, 2015, officers from Kenya’s anti-riot police, the General Service Unit (GSU), beat and kicked Nation journalist Nehemiah Okwembah and Citizen television cameraman Rueben Ogachi at Bombi village on the outskirts of the government-owned Kulalu Galana Ranch in Tana River county.[112] The journalists had interviewed local residents who complained that GSU officers had driven away 200 of their cattle for allegedly trespassing onto the ranch. The officers beat other government officials who tried to intervene on the journalists’ behalf.[113]

Also in Tana River county, on October 13, 2016, Administration Police officers beat Emmanuel Masha, a reporter with the government-owned Kenya News Agency for filming contractors who had stormed county offices to demand delayed pay.[114]

Police have also obstructed, arbitrarily arrested, and detained journalists covering news stories. On May 7, 2016, a senior officer attached to the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) pushed, confiscated cameras and attempted to arrest journalists for filming officers at the scene of the killing of a prominent businessman.[115] In May 2015, officers from DCI interrogated The Standard’s Nakuru county bureau chief, Alex Kiprotich and demanded details of sources for articles regarding an incident in which senior police officers narrowly escaped death after bandits in Baringo county shot at their helicopter.[116]

In a few instances, police appeared to be acting on instructions from other people. On October 17, 2016, officers from the DCI arrested and detained blogger Dennis Owino, who used to blog on corruption issues, for six hours as they consulted with an unidentified individual on phone.[117] They later released him without charge. The officers did not disclose his offense or his accuser.[118] On November 10, 2015, DCI officers who demanded Daily Nation parliamentary editor John Ngirachu’s sources for a corruption story arrested him, and consulted with other people over the phone while he was detained.[119]

Threats

Journalists and bloggers who have criticized the performance of public officials or generally written about sensitive subjects such as public sector corruption have reported being threatened with physical violence. They said that these threats have most often occurred when they wrote about senior national officials, county governors, and police and other security officers.[120] Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 documented 16 incidents of direct death threats against journalists and bloggers across the country between 2013 and 2016, though the actual number is likely to be far higher.

Some of the journalists interviewed said that those who threatened them questioned them about, or warned them against, writing about certain issues or individuals – nearly always national or county-level officials.[121] Journalists and bloggers said they believe the assailants themselves are often members of militia gangs in Nairobi, Kisumu, Kisii and Central Kenya, or known “hit squads,” such as in Nairobi and Eldoret, which seem to be acting at the behest of those who hire them, especially politicians in the lead-up to an election period.[122]

In at least three reported incidents – in Kisumu, Eldoret, and Nairobi – journalists said they later learned police officers had been privately hired or tasked by government officials to intimidate and harass them.[123] One journalist based in a county in the Rift Valley said:

At the end of November 2016, a friend from police in Eldoret showed me an internal circular directing officers to monitor journalists and human rights activists involved in election related activities in this region. On December 10, 2016, I met an intelligence officer based at the National Assembly who told me my name was in the list of journalists and human rights activists being monitored.[124]

In Kisii town, Kisii county, a journalist recounted how police, angry about his corruption stories recruited Sungu sungu militia, an ad hoc gang often used by police and local politicians – to track him down, forcing him to flee the town:

Days after police warned me over my pictures of an officer who had run over four villagers with a truck, Sungu sungu leaders twice came to my house asking for me. They were in a police car. A friendly police officer asked me to leave Kisii immediately to save my life.[125]

In Eldoret, two journalists said they had to relocate to another county after a politician angered by their writing about the Kenyan ICC cases allegedly hired hitmen. The journalists believed the hitmen were linked to the Sabaot Land Defense Forces (SLDF), a private militia, to track them down.[126] They said that with upcoming elections just months away, there have been renewed threats linked to their past reports on Kenyan ICC cases.[127]

In Kisumu town, a photojournalist said individuals known to be members of the “China Squad” and “American Marine” gangs threatened to beat him, as they had done to other journalists and bloggers, if he continued to write negatively about them or the politicians the gangs are associated with.[128] In central Kenya, two journalists said individuals believed to be members of the Mungiki militia gang were routinely hired by politicians and business people.[129] They said the gang members have in the past year intimidated them due to their reporting on upcoming elections and security in the region.[130] In 2016, Inspector General of Police Joseph Boinett warned that armed militia gangs had proliferated in various parts of Kenya and could cause violence in the 2017 elections.[131]

On September 18, 2015, a journalist with a leading daily newspaper said he was threatened while investigating a corruption story involving a judicial officer.[132] A caller, who did not identify himself, warned the journalist to keep clear of matters that did not concern him or face consequences that would include being “shot very many times.”[133]

Intimidation of Foreign Journalists

Foreign journalists have also faced intimidation from officials. In December 2014, Kenyan authorities threatened to ban two Al Jazeera journalists for airing a documentary that exposed police death squads implicated in extrajudicial killings of those suspected of links with the militant group Al-Shabab.[134]

In December 2016, a British journalist with The Times, Jerome Starkey, was detained overnight at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, denied access to lawyers, and later deported for undisclosed reasons, despite having a valid visa in addition to a pending work permit application. [135]

Criminal Charges Designed to Harass

The Kenya Information and Communication Act (KICA), the Media Council Act of 2013, the Penal Code, and the Security Laws Amendment Act of 2014 contain repressive provisions that include heavy fines for media outlets, journalists, and bloggers.[136] The laws have permitted criminal charges under vaguely worded provisions, including “misuse of a communications gadget,” “annoying a public official,” and “undermining the authority of a public officer.”[137] In an important ruling, on April 26, 2017, a Kenyan High Court declared unconstitutional section 132 of the Penal Code, which criminalizes “undermining authority of a public officer,” and said it violates the fundamental right to freedom of expression.[138]

On January 23, 2016, former Nation TV journalist Yassin Juma, according to media reports, was arrested under section 29 of KICA for the offense of “misuse of a communications gadget.”[139] He was detained for two days at Nairobi’s Muthaiga Police station, and interrogated over his social media updates about an Al-Shabab attack on the Kenyan military camp at El Adde, Somalia.[140] His Facebook posts included pictures of the attack, which the cabinet secretary for interior and national coordination, Joseph Nkaissery, had warned would result in the arrest of anyone who disseminated such images.[141] Juma was released without charge after two days.

Four days earlier, on January 19, blogger Edwin Reuben Illah was arrested, according to his own and media accounts, under section 29 of KICA and detained for his Facebook posts about the same attack.[142] He was also released without charge.[143]

On January 5, 2016, Judith Akolo, a Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) reporter, was arrested and detained for hours for retweeting a tweet by a prisons officer questioning the fairness of an internal job advertisement posted by the Directorate of Criminal Investigations.[144] Although Akolo was the 40th person to retweet, and even though she was not charged, she was the only one arrested.[145]

At least seven journalists were arrested and detained between January and February 2016 for condemning corruption and calling for accountability in their respective county governments.[146] In April 2016, a judge ruled section 29 of KICA to be unconstitutional, resulting in all charges pending in court under this section at the time being dropped.[147]

In nearly all the cases documented, policed denied the arrested or detained journalists access to lawyers. In December 2014, blogger Allan Wadi was charged for demeaning the authority of President Kenyatta and within two hours sentenced without legal representation to two years in prison.[148] In January 2016, police turned down KBC’s Judith Akolo’s request for a lawyer as they interrogated her.[149] Another journalist who was arrested and detained for hours over a story on corruption in the Ministry of Interior and National Coordination told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that he specifically asked for a lawyer before writing a statement and was denied:

I told them I could not write a statement in the absence of my lawyer. They told me I did not need a lawyer. We argued for about two hours and my case was referred to their boss who also declined my request of a lawyer. Later I asked a friendly officer what this was all about. He told me it was all intimidation.[150]

Surveillance

Although Kenyan law bars security agencies from intercepting communications without a court order, research by Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 found that Kenyan authorities have in recent years rarely sought court orders to carry out telecommunications surveillance.[151]

Security agencies appear to exploit ambiguities in national laws that regulate interception of communication. While sections 36 and 42 of the National Intelligence Act require security officers to obtain a court order before intercepting any communication,[152] section 36 of the Prevention of Terrorism Act is not clear on this point. Section 36 makes a court order mandatory but section 36(A)(1) allows interception of communication by any security officer in accordance with procedures prescribed by the cabinet secretary.[153] Police and Interior Ministry officials could not confirm whether these procedures have been finalized.[154]

With a general election in August, security agencies appear to have been using this ambiguous provision to carry out surveillance of civil society activists and journalists reporting on sensitive issues.[155]

In February 2017, the Communications Authority directed mobile phone service providers to allow a private company contracted by the government to listen to private calls, read text messages, and review mobile money transactions.[156] In the absence of a data protection law in Kenya, the Communications Authority’s request is prone to abuse, especially during the pre-election period when journalists face increased scrutiny.[157]

Although a judge later stopped the Communications Authority from enforcing the directive, ruling that it violated the constitution,[158] there is little evidence that Kenyan authorities will discontinue a practice that has been going on for so long.

Journalists and bloggers told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that, even before this latest government directive to phone companies, that Kenyan authorities, without court orders, were already tapping calls and text messages of critics, opposition politicians, and journalists. Their statements are backed up by recent research by Privacy International, which notes that intelligence service officers intercept both communication content and acquires call data records without warrants.[159]

Five senior editors at Nation Media Group (NMG) said that when the group founder and majority individual shareholder, the Aga Khan, visited Kenya to attend independence day celebrations on December 12, 2015, President Kenyatta presented him with a report containing phone data of several NMG journalists.[160] The president accused the journalists, most of whom were writing regularly about the controversy surrounding the government’s failure to account for more than half of the $2.5 billion raised from the sale of Eurobond in 2014, of working with the opposition to undermine his government.[161]

One senior editor who attended a meeting with the Aga Khan said:

The Aga Khan talked about the president’s report and told us what Kenyatta’s concerns were. Experts were brought to that meeting to lecture us on how to criticize the government without siding with the opposition.[162]

The five senior editors in separate interviews said that although a qualitative and quantitative analysis by a South African and a Kenyan company of all NMG stories found no evidence that NMG was leaning towards the opposition,[163] NMG management allegedly fired three journalists mentioned in the State House report three months after the visit.[164] They believed the journalists were fired, at least in part, on the basis of the government’s displeasure with the content of their private communications – all collected without a warrant. The CEO of Nation Media Group in Nairobi Joe Muganda, wrote to Human Rights Watch that NMG was “not privy to any meetings between the Aga Khan and Kenyan government officials and hence not competent to comment about the same.”[165] At time of writing, the Aga Khan’s office in Geneva had not responded to our letter regarding these allegations.

In October 2016, the media reported that the principal secretary at the Ministry of Health, Dr. Nicholas Muraguri, had during a recorded phone interview threatened Business Daily reporter Stella Murumba over a story regarding corruption involving Kes5 billion (US$50 million) in the ministry.[166]

According to excerpts of the threats published by the Daily Nation, Muraguri told the reporter:

If that is the thesis of your story, then it puts you at risk. I am following you. You proceed. You don’t know government. We can get what you write even before you publish it, including getting print shots and screenshots of the story. Someone can be reading your messages while sitting here.[167]

Although Muraguri apologized to the reporter following the media’s publication of his threats, Kenyan authorities made no attempts to deny Muraguri’s claims about the government’s involvement in surveillance of journalists.[168]

Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 documented five other incidents in which the phones of journalists and bloggers appear to have been tapped between 2014 and 2016. One broadcast journalist said that people who introduced themselves as DCI officers called back three separate times in 2016 after she conducted phone interviews to question her on the specifics of her call.[169]

Another reporter with a leading Kenyan media outlet said senior officers from the Kenyan military questioned him in 2015 about a story related to the military that he had yet to publish but had just finished discussing with his supervisor by phone.[170] Puzzled over how the military could have known about the story within minutes of their phone call, the editor and the journalist opted not to publish, fearing for the journalist’s safety.[171]

Withholding and Withdrawal of Advertising

In Kenya, government advertising accounts for between 60 to 70 percent of all advertising to media, which accounts for more than half of total media revenue.[172]

In February 2017, Kenyan authorities banned government ministries, departments, and agencies from placing state advertisements in private media.[173] President Kenyatta’s chief of staff and head of the civil service, Joseph Kinyua, directed state accounting officers, who are responsible for placing government advertisements, to advertise only in a new government publication, My.Gov, which was initially created in 2015 as an online portal.[174] The government publication is now being published as paid inserts in the four newspapers, The Daily Nation, The Standard, The Star newspaper and People Daily, the latter owned by the Kenyatta family.

While Kinyua portrayed this as a cost-cutting measure, media professionals interpreted it as part of government’s strategy to avoid remitting long-delayed payments for advertising already published. [175]

Editors, reporters, and sales executives told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that Kenyan authorities started withholding advertising and payment for published advertisements in 2013.[176] Several senior editors and a media analyst said that soon after Kenyatta took office in 2013, the government, contravening the contract according to which all advertisements should be paid for within three months of being published[177] – withheld payment for advertising already published for more than six months until newspapers agreed to an array of demands. Such demands include toning down criticism of the government, especially in matters related to unfulfilled election promises from 2013 and other sensitive topics such as corruption, security, and land.[178] When the Kenyatta administration agreed to start paying for advertising already published, payment was piecemeal and mostly conditional on positive coverage.

Senior editors said that as of November 2016, the government was withholding Kes2 billion [US$20 million] in advertising money owed, some dating back more than 18 months.[179] Of this, Standard Group estimates that its print and electronic outlets were jointly owed Kes400 million [US$4 million],[180] Nation Media Group Kes500 million [US$5 million],[181] Royal Media Services Kes200, million [US$2 million], and Radio Africa Group Kes90 million [US$900,000].[182]

At time of writing, we did not receive a reply from Joseph Mucheru, the cabinet secretary for Information, Communications and Technology, to our research queries. On May 2, 2017, he said by telephone that he needed to consult with the Attorney General on whether to respond to our questions, including about alleged withdrawal of advertising and withholding of revenue. On May 3, while addressing journalists during a World Press Freedom Day event, Mucheru denied that the government was using advertising to stifle press freedom.[183]

On April 11, Denis Itumbi, senior director of innovation, digital and diaspora communication in the office of the president, told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that the government was not using advertising to exert pressure on the media. He said: “There is no advert that media agrees to run without a signed Local Service Order. They are saying by signing the LSOs that they agree to delayed payment. Media houses agreed without coercion to sign LSOs that are not time bound.”[184]

A senior editor at Standard Media said:

Any time we publish anything negative about Kenyatta and Ruto, we receive threats from government officials and then all government advertisements to Standard Group gets frozen.

The situation appeared to have worsened with the new government policy of centralized advertisement, which the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology started to implement in July 2015. The then Cabinet Secretary Dr. Fred Matiangi announced in May 2015 the establishment of a new state agency, the Government Advertising Agency (GAA), to handle all government advertising and payments to media outlets for advertising already published.

One NMG editor recounted how senior government officials made frantic efforts, including withdrawing advertising and withholding advertising revenue by the GAA, to stop media reporting on the disappearance of Kes150 billion (US$1.5 billion), part of what had been realized from Eurobond sale.[185] Another NMG editor said the GAA withheld advertising after one of its publications, Business Daily, revealed the misappropriation of Kes5 billion [US$50 million] in the Health Ministry.[186]

Another Standard editor said:

GAA decides where to take their revenue based on how you have carried your stories. Standard now is being denied advertising because of a recent photo in the Nairobian, our sister publication, showing one of President Kenyatta’s sons carrying about Kes2 million [US$20,000] in cash and dishing it out to patrons in a Nairobi club.[187]

He said that Denis Itumbi asked him to remove the story from the Standard website. “I declined,” the editor said.

Once this kind of thing happens more than once and advertising starts diminishing, editors start coming under pressure from the CEO to go slow on the government. That is what brings about self-censorship. If you don’t go slow, you get fired.[188]

When contacted, Itumbi denied the allegation saying: “What story is big enough for us to want to pull it down? This government and Denis Itumbi in particular has no interest in asking any journalist or media outlet to pull down a story.”[189]

Self-Censorship

Facing threats, intimidation, physical attacks, and criminal prosecution, journalists and bloggers said they self-censor to stay safe.[190] Journalists’ decisions to curtail reporting on sensitive or controversial issues could have a pronounced effect on Kenyans’ access to information on key issues prior to the August elections.

Some journalists said that they steer clear of any reporting that may attract government attention or sanction. About three dozen reporters in Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia, and Kisumu counties told Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 that, although there are many cases of irregular land transactions and corruption in both the national and county governments, they felt it was too dangerous to report on these issues.[191]

Journalists said that several media outlets in Kenya are reconsidering the value of having investigative desks that, among other things, expose government abuses.[192] At least two mainstream media outlets have either disbanded or scaled-down investigative desks because of security concerns and the financial costs of running such desks. To avoid conflict that could affect the newspaper’s financial stability, one senior editor wrote to the office of the president in February 2015 promising never to write negative stories about the president and his family.[193]

Journalists said that as of November 2016, senior editors in at least three media outlets in Nairobi urged their staff to tone down reportage on corruption in the government as well as security operations and abuses by security agencies.[194] A Nairobi-based editor said:

Whenever we write articles critical of security agencies or exposing corruption in the government, our reporters receive death threats from security and other government officials. This is usually followed up with withdrawal of government advertising or withholding of revenue from advertising. We now have to assess carefully whether such stories are worth the cost.[195]

Journalists said that the government’s insistence on conditioning advertising and release of payment for advertising on positive coverage meant they routinely come under pressure from sales executives and editorial senior editors to tone down criticism of the government. Just months before the government announced a total ban on advertising to private media, one editor conceded: “We have started acceding to the demands to tone down. Otherwise we lose government advertising or the money for adverts already published gets withheld.”[196]

III. Lack of Accountability for Abuses

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has stated that governments “should put in place effective measures to protect against attacks aimed at silencing those exercising their right to freedom of expression.” Attacks on journalists including arbitrary arrest, torture, threats to life, and killing because of the exercise of their activities is inconsistent with a free media. As the committee noted, “All such attacks should be vigorously investigated in a timely fashion, and the perpetrators prosecuted, and the victims, or, in the case of killings, their representatives, be in receipt of appropriate forms of redress.”[197]

Journalists and bloggers alleged that, despite reporting incidents to police, existing accountability institutions such as the National Police Service Commission (NPSC), Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), Internal Affairs Unit (IAU), and the office of the Inspector General of Police (IGP) have failed to ensure accountability for abuses against the media.[198] This lack of police response is not limited to attacks on the media: Kenyan police have a history of either not responding adequately to crimes or failing to investigate them.[199] Officials from journalist associations attributed the lack of credible investigations by the police into attacks against journalists and bloggers to the hostile media environment in the country.[200]

In the cases of the two journalists who died under suspicious circumstances, Human Rights Watch and ARTICLE 19 found that the police investigations had been inadequate. Police had at time of writing not interviewed possible prime suspects, despite having useful leads. Friends and relatives of John Kituyi in Eldoret said they had given police several possible leads into his killing, but that there was no indication that any of these individuals had been questioned.[201]

A journalist in Kisumu said that after he repeatedly inquired about the progress of investigations into his assault by two police officers in October 2014, police took him into custody and detained him in a secret cell at a police station.[202] In Eldoret, a journalist who was kidnapped outside his house in March 2015, and briefly held by unknown assailants, said he gave up pursuing a police investigation due to lack of response.[203]

In Nairobi, Florence Wanjeri Nderu, a renowned human rights and anti-corruption blogger who in 2015 was injured around her left eye by unknown assailants, said that even though she made a detailed report of her attack at Langata police station in Nairobi, police have failed to investigate the case. “They have never even visited the scene of my attack or followed up with me,” she said. “Yet I have seen the same man who attacked me four times around the same place where he attacked me.”[204]

However, there has been limited progress in some cases. IPOA’s director of Investigations, Elema Halake, said his authority has been investigating at least three cases of police beatings of journalists.[205] He cited investigations in the case in which alleged GSU officers beat and injured journalists Nehemiah Okwembah and Reuben Ogachi Ogada in Tana River in 2015 that are now complete. The files are due to be forwarded to the Director of Public Prosecutions for prosecution.[206]

In one case a victim received some limited redress, but no actual justice: Duncan Wanga, a cameraman with the Kenyatta family-owned K24 television, was beaten by a senior police officer in Uasin Gishu county and his camera damaged while covering demonstrations in September 2016.[207] The officer apologized and compensated him for the damaged camera.[208]

George Kinoti, director of communications at the National Police Service, said that, in the event that all the accountability mechanisms fail to investigate or prosecute attacks, affected journalists and bloggers should escalate the matter with the Inspector General of Police.[209]