"All the Men Have Gone"

War Crimes in Kenya's Mt. Elgon Conflict

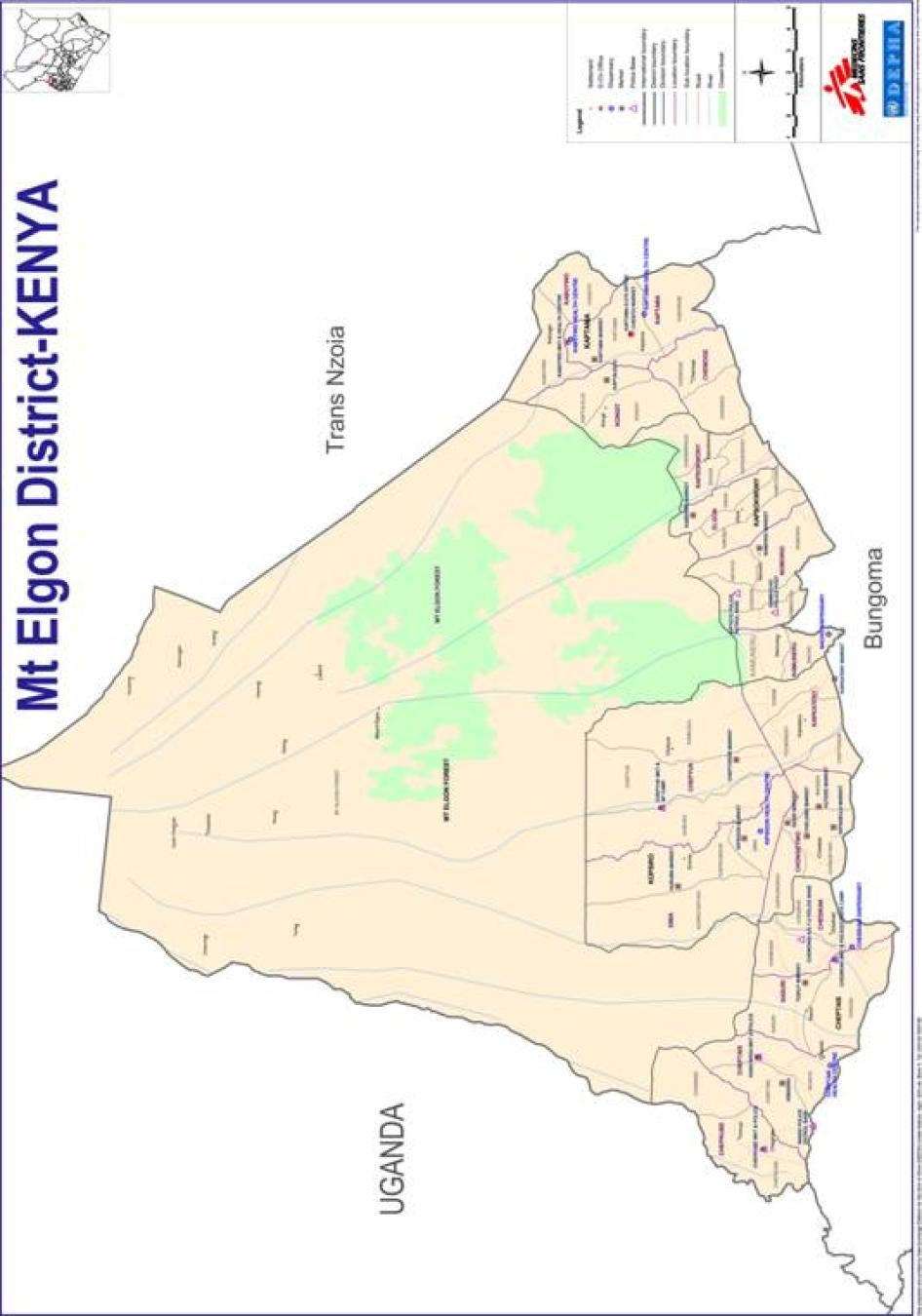

Map of Mt. Elgon, Kenya

Summary

Civilians in Kenya's western Mt.Elgon district near the border with Uganda have been twice-victimized in a little known conflict between Kenyan security forces and a militia group known as the Sabaot Land Defence Force (SLDF), forcing tens of thousands to flee their homes.

Since 2006 the SLDF has attacked thousands of civilians, killing, raping, and mutilating, in a complex mix of land disputes, criminality, and struggles for local power. The government's security response, initially lacklustre, was massively stepped up in early 2008 after Kenya's disputed elections by the introduction of the Kenyan armed forces. In a joint army-police operation, the security forces conducted mass round-ups of thousands of men and boys, tortured hundreds if not thousands in detention, and unlawfully killed dozens of others. Residents are supportive of action against the SLDF but have been horrified and traumatized by the way in which the operation has been carried out.

Both the SLDF and the Kenyan security forces have been responsible for serious human rights abuses. To the extent that the fighting in Mt.Elgon has risen to the level of an armed conflict, both sides have committed serious violations of international humanitarian law (the "laws of war") that amount to war crimes.

The Kenyan government has a responsibility to promptly and impartially investigate and prosecute the individuals responsible for these crimes. Thus far the official response has been muted and insufficient. While trumpeting SLDF abuses, government officials have persisted in denying reports of torture by the security forces even as the evidence has piled up, with reports and publicity in recent months from local human rights organizations, local media, Human Rights Watch, the Nairobi-based Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU), and the constitutionally independent state human rights organ, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

Local human rights activists and journalists who have investigated and exposed abuses by both the SLDF and the security forces have been hounded. Two prominent activists were sought by the military after issuing a joint statement with Human Rights Watch in April 2008. Both left the country for a short time.

Eventually, in June, the authorities announced an internal police investigation into torture allegations–but have not made public the terms of reference or degree of independence of such an inquiry. An internal investigation by security organs who are responsible to the same ministers and commanders who should be investigated is unlikely to provide answers to the questions that need to be asked. Was arbitrary arrest, detention, and torture planned from the outset? At what level were officials aware of what was going on and why did they not take immediate steps to end the abuses once they were known?

Human Rights Watch is therefore calling for an independent public inquiry to transparently examine the responsibility of senior police and military commanders and government officials and ministers, to look at grievances and consider compensation for victims of human rights abuses and wanton destruction of property by the security forces.

In addition, criminal investigation into persons responsible for torture, extrajudicial killings, and other abuses by both the SLDF and state security forces should be stepped up. Those who fund and otherwise support the SLDF should be investigated and prosecuted. Families should be properly informed of deaths in custody and the bodies of their relatives should be returned. The authorities should allow unimpeded access to humanitarian agencies to support the displaced communities, and provide medical attention to detainees.

The conflict in Mt.Elgon has long been ignored by the Kenyan government and has escaped international attention. While its roots lie in conflicts over land, as with most organized violence in Kenya it is closely related to politics. Various militias have existed since the early 1990s in Mt.Elgon, funded and manipulated by local politicians to their advantage.

The history, organization, and funding of the SLDF is an example of the relationship between land grievances and the manipulation of ethnicity and violence for political ends that is a disturbingly deep-rooted and longstanding element of the Kenyan political process. This came to prominence in the violence, much of it orchestrated, in the Rift Valley and Western Kenya in early 2008 in the wake of the disputed presidential election of December 27, 2007.

The violence following the elections shocked the world-and many Kenyans-into recognizing the scale of the governance failures within the Kenyan political system, and the explosive consequences of repeated failures to address historical injustices and accountability for abuses. The depth of organization manifested in the SLDF and the long-lasting nature and scale of the human rights problems in Mt.Elgon are a particularly extreme illustration of the dangers of lack of action by the authorities allowing impunity for those involved in organized crime and human rights abuses.

The Sabaot Land Defence Force (SLDF) is a non-state armed group that first emerged in 2006 to resist government attempts to evict squatters in the Chepyuk area of Mt.Elgon district. Since its formation, the militia's activities have expanded, becoming more violent and more overtly political. In the run up to and following the 2007 general election the SLDF supported certain political candidates and targeted political opponents and their supporters.

The security response, initially police-led, failed to contain the rapidly evolving armed group as it wreaked havoc in Mt. Elgon and parts of Trans-Nzoia districts. Thousands of people have been displaced as a result of SLDF activities and clashes between the militia and security forces. Estimates of the numbers of people displaced by the violence range between 66,000 by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights and 200,000 by the army, as of April 2008.

According to Kenyan human rights groups, since 2006 the SLDF has killed more than 600 people, has kidnapped, tortured, and raped men and women who opposed them or their political supporters, and has kidnapped and tortured people who owned land that members of the militia coveted, forcing the owners to choose between mutilation or surrendering their property. They have collected "taxes" from the population and they effectively ran a parallel administration, punishing civilians by cutting off their ears and sewing up their mouths if they defied the militia.

In March 2008, after the December 2007 election, the Kenyan army was deployed to regain control of Mt.Elgon district, in a joint operation with the police called 'Operation Okoa Maisha' ('Save Lives' in Swahili). Local residents initially welcomed the crackdown but were quickly alienated by the strategy pursued by the security forces. The scale of the human rights violations committed by the Kenyan security forces in the course of their operations against the SLDF, in particular systematic torture, is truly shocking.

Victims described to Human Rights Watch how military and police units rounded up nearly all males in Mt. Elgon district, some of them children as young as 10. At military camps, most notoriously one called Kapkota, every detainee appears to have been tortured and forced to identify members of the SLDF or the location of weapons. Security personnel beat them with sticks, chains, and rifles. Some people died as a result and their bodies were removed in helicopters for disposal in the forest. Suspects were then 'screened' by walking past informers who decided if they were members of the SLDF or not. Significantly, the screening took place after the initial torture. Most were then released, some with very grave injuries. The others were detained, some tortured further and then either "disappeared" by the military or handed over to the police and taken to jails at Bungoma and Kakamega.

Local human rights groups say they have documented 72 people dead and 34 missing since the beginning of the operation on March 9 and the end of June 2008; a source within the operation put the figures even higher, saying up to 220 have been extra-judicially killed. According to the military's own figures they have detained nearly 4,000 people. Of these, the military say they transferred around 800 to jail. As of June 2008, about 758 SLDF suspects have been arraigned in court on charges of promoting war-like activities, although many of these have since been bailed.

Human Rights Watch saw several bodies in local mortuaries that attendants said had come from Kapkota camp. They showed visible signs of torture such as welts, bruises, broken bones, rope burns on wrists and feet, and swollen soft tissue. According to local human rights workers, over 450 detainees including 32 children of school-going age, were held in extremely congested conditions in Bungoma jail during March, April, and May 2008. They were initially denied adequate medical attention, despite the fact that five have died in custody from their wounds, and others remain in critical condition.

The Kenyan security forces are legally bound by international human rights law, much of which has been incorporated into domestic legislation. The Kenyan constitution and human rights law provide fundamental due process guarantees for all individuals in detention. At all times, the prohibition on the use of torture and inhuman and degrading treatment is absolute.

Since the beginning of the joint army-police operation in March 2008, fighting in Mt.Elgon appears to have risen to the level of an internal armed conflict under international humanitarian law (the laws of war). This law is applicable in situations of armed conflict that rise above internal disturbances and tensions such as riots or sporadic acts of violence. Relevant law includes article 3 common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and customary international humanitarian law.

All parties to the conflict, both government security forces and the SLDF, are obliged to act in accordance with the law on the conduct of hostilities and to protect civilians and captured combatants. SLDF military operations that are permissible under the laws of war will still violate Kenyan criminal law, for which SLDF members may be prosecuted. These would include offenses such as murder and attempted murder, weapons possession, promotion of war-like activities, and conspiracy.

The Kenyan government has tasked the police to look into allegations of torture, however, the United States and United Kingdom should suspend military and other assistance to the Kenyan security forces until the allegations of serious offenses committed in Mt.Elgon are properly investigated and appropriate action is taken to ensure accountability.

Methodology

This report is based on field investigations by Human Rights Watch in the Mt.Elgon area during March and April 2008, and follow-up research from London in May and June 2008 and in Nairobi in July 2008. In March and April 2008 Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 victims and eyewitnesses as well as members of the police force and army, government officials, journalists, human rights activists, medical staff, and humanitarian workers for this report.

Human Rights Watch also collaborated with Kenyan human rights activists who have long tried to bring a national spotlight to bear on the Mt.Elgon situation. These include but are not limited to Mwatikho Torture Survivors Organization, Western Kenya Human Rights Watch (WKHRW),[1] and Western Kenya Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.

To ensure that Human Rights Watch obtained a full spectrum of views and experiences of the conflict, interviewees were selected from different ethnic groups, (Sabaot, Bukusu, and Teso), different political affiliations (Orange Democratic Movement, Party of National Unity, and SAFINA) and from different locations on the mountain, with the assistance of different Kenyan and international organizations working in the area. Human Rights Watch researchers visited eight locations in the area, including Kitale, Bungoma, Kapsokwony, Cheptais, Sirisia, Lwandanyi, Malakisi, and Lwahaha.

Recommendations

To the government of Kenya

- Issue urgent, clear, and public orders to military and police commanders to immediately cease torture and mistreatment of individuals detained in the context of the Mt.Elgon operations and allow unimpeded access of independent humanitarian monitors and medical assistance to detainees.

- Investigate all claims of unlawful killing, arbitrary arrest and detention, torture, rape, and destruction of property by security forces and prosecute those responsible. Criminal investigations should trace any orders to commit such acts to the highest level of commander implicated. Criminal investigations should also address the issue of those criminally responsible under the principle of command responsibility, i.e. those who were in a position to prevent or punish such action and failed to do so.

- Open a public inquiry into abuses by the security forces in Operation Okoa Maisha; including looking at the formation of policy, operating procedures and command responsibility for joint operations. As part of such an inquiry, establish mechanisms to record grievances by those who have lost relatives, homes, or sustained injuries as a result of the actions of the security forces and make provision for their compensation.

- Open or re-open impartial criminal investigations into local politicians and leaders implicated in unlawful support for the SLDF.

- Ensure fundamental due process guarantees to persons in detention, including the right to have their detention immediately reviewed by an independent judicial authority with power to order their release, and to have access to legal counsel, family members, and medical care. All persons detained due to suspicion of having committed a criminal offense should be charged or released. If charged they should receive a trial before an independent court meeting international fair trial standards. Persons detained illegally should receive compensation.

- Where appropriate, children in detention should be released without charge back to the care of their families as child combatants and provided with psycho-social care and support.

- Release or transfer detainees in unofficial detention centers on Mt. Elgon such as Kapkota and Kaptama to official detention facilities and cease using those places for detention; ensure that all prisoners detained in Bungoma and Kakamega jails as well as those detained as a result of the operation in police cells throughout the region have immediate access to medical attention, family members, and legal counsel; and find alternative accommodation for detainees in gazetted locations so that overcrowding in Bungoma jail can be eased.

- Grant access to Kenyan prisons for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) so they can independently and confidentially monitor prison conditions and help connect missing persons with their families.

- Recover the bodies of those killed by the security forces and dumped in the forest or elsewhere and deliver them to local mortuaries where they can be identified and buried by relatives.

- Establish an independent civilian-led inspectorate to independently investigate allegations against the police or military when they occur.

- Make comprehensive land reform a major priority in the commissions dealing with reform in Kenya. The proposed National Land Commission should prioritize investigating allegations of illegal land deals at Chepyuk, demarcating the forest boundary fairly and clearly and compensating those who unfairly lost their land.

To the SabaotLand Defence Force (SLDF)

- Immediately cease killing, torture, mutilation, and rape of all persons and issue clear and public orders to all commanders to abide by international humanitarian law, especially with respect to civilian protection.

- Appropriately discipline any member against whom there is evidence of participation in violations of international humanitarian law.

- Facilitate full and unimpeded access of independent humanitarian assistance to civilians in need.

To the governments of the US and UK

- Suspend police and military assistance and cooperation programs until the Kenyan military and Kenyan police fully investigate and take appropriate action regarding allegations of torture and other abuses by their forces.

- Establish or implement existing screening mechanisms (such as the US Leahy law) to investigate allegations of abuses and deny further training opportunities to individuals implicated in serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law.

Background

The cumulative consequence in Kenya of land theft, illegal or chaotic land allocation, forced evictions, corruption, impunity, and the manipulation of ethnicity for political purposes over decades is a culture of violence and widespread abuse of human rights. This was witnessed most recently and dramatically in the violence, much of it orchestrated, that followed the flawed presidential election of December 2007.

The roots of the current conflict in Mt.Elgon are no different. All of these factors have played a key role in the successive waves of violence and insecurity that have wracked the district since 1991, and that have led to the death, dispossession, torture, and repression of thousands of people, the vast majority of them civilians.

Land Disputes

Land is at the heart of the conflict in Mt.Elgon. While there are several other contributing factors to the insecurity and displacement seen in the area since 1991, disputes over land have been constant. As is the case in much of Kenya, these land disputes have their roots in the colonial era, but current grievances center on how those disputes have been managed and the politicization of the various attempts to resolve earlier displacements through resettlement schemes. Nevertheless, the history of land ownership is the key to understanding the current conflict, and indeed the recent and previous patterns of violence in other parts of Kenya.

Mt.Elgon district and neighboring Trans-Nzoia district lie close to the border with Uganda on the slopes of Mt. Elgon, Kenya's second highest peak. The area is primarily inhabited by members of the Sabaot community, but other inhabitants include the Ogiek, Bukusu, Teso, Sebei, and various Kalenjin sub-groups.[2]

Many Sabaots were displaced from the arable areas of Trans-Nzoia district when the British colonial government appropriated their land for settler farms in the 1920s and 30s. They moved to two areas-Chepkitale and Chepyuk. In 1932 a group of Sabaot presented their grievances to the Kenya Land Commission, a body set up by the British to investigate land disputes. The British acknowledged their case and discussed a compensation package, but it was never implemented.[3]

In 1968 the recently independent Kenyan government compounded the problem and reduced the area available for the expanding population at Chepkitale by designating it as a game reserve, and forcing the inhabitants to leave. This was done without any consultation or compensation. The surrounding area was a forest reserve and was thus also unavailable for settlement and grazing.

Inhabitants complained, and in 1971 the government initiated a resettlement program for the displaced at the other location, Chepyuk. Unfortunately, some of the land that was supposed to come from redesignated parts of the forest reserve had already been illegally settled by families who had moved to Chepyuk in the original displacement, and who were themselves also facing land pressure. In effect, the government was trying to force the inhabitants of two villages into the area occupied by one.

Conflicts arose between the intended owners and the existing inhabitants, polarizing relations between the displaced who had originally moved to Chepyuk and those who originally had gone to Chepkitale, the ones who had gone 'up' the mountain and the others who had gone 'down.' Moreover, the resettlement exercise was placed in the hands of area chiefs, local land officials, provincial administrators, councillors and members of parliament, many of whom were accused of corrupt practices in the allocation of land.

The government evicted people originating from both areas from various locations that had been designated parts of the settlement scheme, and made a second attempt to allocate the land, known as Chepyuk II in 1989. This was equally controversial. People from Chepkitale who did not receive their allocation tried twice, in 1979 and 1988, to return to Chepkitale, but were forcefully repulsed by the police since the area was now a game reserve.

Representatives of both groups made petitions to the government. In 1993 the government of President Daniel arap Moi annulled the Chepyuk settlement scheme completely and ordered the creation of a third scheme, Chepyuk III. By now the population had increased even further and people had been living for more than a generation on land whose status had not been formalized. Because of controversy and complications, phase three was never fully implemented and remained an apparently dormant issue throughout the 1990s. However the issue had not been resolved and anger was growing.

Corruption and Politics: The Origins and Objectives of the SLDF

Members of both groups (those who went to Chepyuk and those who went to Chepkitale) were the intended beneficiaries of Chepyuk III, and the implementation of the program was a major local issue in the 2002 general elections and the 2005 referendum on the constitution. Much of the constitution debate was about the structures of local government control and who would get to adjudicate on land disputes.

After the 2005 referendum, the third phase was finally implemented, but, as noted by the Kenya Land Alliance in 2007, the exercise was marred by "massive irregularities."[4] The Kenya Land Alliance report quotes a member of the vetting committee that decided on beneficiaries admitting that they were "under pressure from political leaders not to give land to people seen as sympathetic to those posing a political threat to leaders at that time."[5] This was a feature of the broader political conflict between the then sitting member of parliament for Mt. Elgon, John Serut, and his then protégé the future MP, Fred Kapondi (they later fell out and became political rivals).

According to the Kenyan NGO Western Kenya Human Rights Watch (WKHRW),[6] which has investigated and reported on human rights abuses by all parties in Mt.Elgon, the Sabaot Land Defence Force emerged as an armed group immediately after the December 2002 general elections. WKHRW claims that recruitment of fighters began in March 2003 and training, at camps in the forest, began in July 2003.[7]However, violent attacks did not begin in earnest until 2006, in the wake of the implementation of the phase III resettlement program when the SLDF resisted attempts to reallocate land, and then in the run-up to the 2007 elections when they targeted political opponents of Fred Kapondi, in particular supporters of his erstwhile colleague and now rival, John Serut.

The SLDF is an armed group organized and funded by local politicians, although the actual politicians in control have changed over time.[8]The SLDF is very similar in its activities to the majimboist groups that were armed by the state in 1991-92 and 1996-97 to drive out non-Kalenjin groups (mostly Luhya in Mt.Elgon) who were unlikely to vote for the ruling KANU party.[9] This happened in Mt.Elgon, as well as across the Rift Valley and coastal provinces in the elections of 1992 and 1997.[10] The political objectives of the SLDF become clear when one looks at the pattern of attacks, the ethnicity and political affiliation of the victims, and the relationship between the timing of violence and the electoral cycle. Basically, the SLDF, as with many other armed groups in Kenya, has twin purposes, on the one hand land-related objectives, and on the other to further the political aims of certain local leaders.

Command Responsibility within the SLDF

To residents of Mt.Elgon, the members and leaders of the SLDF, including the founders, sponsors, and political beneficiaries, are well known. A wide range of human rights activists, journalists, chiefs, and assistant chiefs, retired civil servants and other civilians named the leaders of the SLDF as the late Wycliffe Matakwei, John Sichei Chemaimak, John Kanai, Cllr. Nathan Wasama, Jason Psongywo, Patrick Komon, and Cllr. Benson Chesikaki.

Of these, Wycliffe Matakwei admitted to being the deputy leader of the SLDF in a television interview.[11] Accompanying Matakwei at the interview were Fred Kiptum, the SLDF's alleged spiritual leader and local politician John Kanai.[12] Residents claimed that Psongywo and Komon were among those who grabbed land illegally in phase one of the Chepyuk settlement scheme. Matakwei was allegedly killed by the police in May 2008. The police paraded his body and his wife positively identified the body.[13] Kanai, Psongywo, and Komon are now in custody, awaiting trial. John Sichei Chemaimak recently appeared in an interview on Kenya Television News (KTN), claiming to be the true leader of the SLDF. He is apparently on the run in Uganda.[14]

Benson Chesikaki was elected to the County Council of Mt. Elgon in December 2007, representing Emia ward. One chief described Chesikaki and Matakwei coming to his area in 2007 recruiting boys to join the SLDF: "They said all young men should go for training. Many of them did not. Those who didn't had to flee."[15] Many other witnesses cited him as a known and feared leader of SLDF.[16] Nathan Wasama was elected unopposed as a councilor in Sasuri ward. Wasama is widely implicated in SLDF activities by residents and local officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch[17], but he was nonetheless secretly sworn in, in the council chamber at Kapsokwony, in January 2008. Chesikaki and Wasama are now in custody.

Wilberforce Kisiero, the MP for the former ruling party KANU between 1982 and 1997 was widely cited as one of the proponents of violence in the district.[18] He was implicated in the state sponsored clashes of 1991-93, and named in the Akiwumi report, the parliamentary investigation into the political violence of the 1990s.[19]

Kisiero and John Serut, the MP from 2002 to 2007, and Fred Kapondi, the current MP elected in 2007, were accused by local residents and human rights organizations of working to recruit, train, and finance militia who intimidated opponents in the 1997, 2002, and 2007 elections.[20]

Having initially worked together (Kapondi was formerly KANU party chairman in the district), by the time of the most recent election of 2007 Serut and Kapondi had fallen out, according to residents. After that, the SLDF began to target supporters of Serut, including Serut himself. An area chief explained that because Serut supported the Chepyuk III settlement scheme against the wishes of most within the SLDF, "Kapondi got a chance to run the boys," and this gave him the political powerbase he needed to win the election.[21]

A neighbor of Kapondi told how he was repeatedly harassed by SLDF 'boys' who had a training camp on Kapondi's land.[22] Another chief described Kapondi leading a recruitment drive in his area for young men to join the SLDF in 2006.[23] Kapondi was arrested in April 2007 and charged with robbery with violence in Webuye court, a non-bailable offense. He was nominated as the ODM candidate while in custody and acquitted on December 13, 2007, just days before the election. Court officials told Human Rights Watch that the prosecution case collapsed when witnesses started disappearing and others changed their stories.[24] Human rights activists described seeing the court packed with known SLDF militia during hearings.[25]

Kapondi and others were also named in parliament by the then MP, John Serut, accused of fueling the clashes.[26]But Serut himself, along with Kisiero and another former MP, Joseph Kimukung, were named by the government spokesman in a report seeking to identify the backers of the violence.[27] Local residents say they have all been involved at various stages.[28]

When Human Rights Watch asked the Mt. Elgon District Commissioner about the allegations against Kapondi and the other councilors whom it is claimed are among the leaders of the SLDF, he expressed surprise. He said he had a good working relationship with all of the people mentioned, especially Benson Chesikaki, who, as chairman of the County Council, is involved in the operation to combat the SLDF.[29] When Human Rights Watch asked a senior policeman at the district headquarters in Kapsokwony why the councilors were not the subject of criminal investigations, he just laughed.[30]

Other Militia in the Area

In the absence of a concerted response by the government to the SLDF, and in the context of competitive displacement in the run-up to the elections, groups sought to displace supporters of their opponents so they could not vote, while other militia groups emerged on Mt. Elgon and in neighboring Trans-Nzoia district in the latter half of 2007 and early 2008 allied to different politicians and different ethnic groups. The two main groups were the Political Revenge Movement (PRF) and Mooreland Forces.

The PRF was associated with former Kitale MP Davis Nakitare, who was arrested along with 205 youths undergoing military training on his farm in the Rift Valley on February 25, 2008.[31] Eventually the youth were released and Mr. Nakitare was released on bail.

The Mooreland Forces are associated with families that originally came from Chepkitale who are at odds with the SLDF over their fair share of the land at Chepyuk settlement scheme. The Mooreland Forces have defended residents against SLDF atrocities. In the worst bout of fighting, Mooreland and SLDF clashed in January 2008; four days of fighting reportedly left 32 dead.[32]

Following the December 2007 elections, displacement of families across Mt.Elgon and Trans-Nzoia districts increased further as the SLDF sought to exploit the insecurity to drive unwanted populations and political opponents from the mountain completely. In March 2008, after clashes elsewhere in the country had died down, the Kenyan government initiated a joint military-police operation to deal with the SLDF "once and for all."[33] That operation, marred by grave human rights abuses, is ongoing at the time of writing.

Abuses by the SabaotLand Defence Force (SLDF)

Scale and Scope of SLDF Atrocities

Since their emergence in 2006, the SLDF has committed serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law against the population of Mt.Elgon that amount to war crimes.

From 2006 to 2008 the SLDF was in effective control of the whole Mt.Elgon district, according to local leaders.[34] "There was no government in that area," said a government official in Nairobi.[35] As a retired civil servant who was abducted by the SLDF put it, "The SLDF were like the government but their laws were crazy."[36] They intimidated the population, raped and stole property at will, collected "taxes", and administered their version of justice. "They have their own system of justice: pay a fine or be cut [lose an ear]," explained one assistant chief from Mt.Elgon.[37]

Hundreds of people have been burnt out of their homes by SLDF fighters. Thousands more have fled the area for fear of being caught up in their violence, and the violence of the post-March 2008 crackdown. In July 2007 the Kenya Red Cross estimated that a total of 116,222 people had been displaced in Mt.Elgon and neighboring districts-"this is almost the entire population of Mt.Elgon".[38]At the end of the year, the IDP Network of Kenya estimated at least 70,000 fresh displacements in Mt.Elgon during 2007, claiming that "actual figures are likely considerably higher."[39] Later in April 2008, the Kenyan Department of Defence put the total number displaced as a result of SLDF operations at "almost 200,000."[40]

The number of people killed by the SLDF has steadily grown. In July 2007 the Kenya Red Cross put the number of dead at 253, with 184 killed as a result of gunshot wounds, cuts, and burns.[41]In early April 2008 WKHRW reported it had documented 615 deaths from 2006 up to February 2008.[42] Even the local MP, John Serut, was targeted, surviving an assassination attempt when gunmen opened fire at him as he gave a speech outside the District Commissioner's office in Kapsokwony in May 2007.

The SLDF not only killed hundreds who were perceived to oppose them or their objectives but they also tortured and maimed inhabitants who broke their code. They forbade drinking alcohol. They demanded "taxes" from all those with a regular income; civil servants, for example paid between 3,000 and 10,000 shillings per month (US$50-150) depending on rank.[43] Some victims spoke of attacks targeted at individuals who had land disputes with other landowners close to the SLDF or who hired the SLDF to intimidate.[44]

In order to sustain itself the SLDF fed off the local population. Multiple victims and witnesses spoke of random acts of theft and terror committed by SLDF militia.[45] The militia forcefully recruited young boys to join them. In 2006, WKHRW estimated that 650 children of school-going age (under 18) had been forcefully recruited into the SLDF.[46] It described parents having to choose between paying a fee of 10,000 shillings ($150) or surrendering their child.

In the run-up to the 2007 elections, dozens of victims and eyewitnesses described politically motivated attacks against supporters of outgoing MP John Serut of the PNU party, formerly of FORD-Kenya, as well as against opponents of candidates supported by the SLDF. The SLDF was in favor of candidates seeking election to the county council on the ODM (Orange Democratic Movement) ticket.

Serut had worked with the SLDF previously but fell out with the commanders before the 2007 poll.[47]More widely, victims and human rights organizations complained about attacks against people of Bukusu ethnicity, on the basis of their ethnicity alone, because they were seen as unlikely to vote ODM in the general election. Many Bukusu were displaced over the constituency border into Sirisia, part of Bungoma district that neighborsMt. Elgon. This follows a pattern of attacks that have recurred in every election since 1992. Further, the SLDF continued to harass the population there by cutting the pipe that brings water down the mountain to Sirisia. As of March 2008, the people there had been without running water for four months.[48]

The insecurity has severely affected the livelihoods of the population of the district. Schools have been closed, planting has been disrupted, and businesses have suffered. The humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) called the violence "a daily reality that affects peoples' ability to access needed health care and food."[49] The Kenya Red Cross warned in mid-2007 that over 30,000 livestock had died, the cost of maize had risen to unaffordable proportions, and more than 9,000 hectares of cultivable land had not been planted.[50]

Deliberate Killings and Abductions of Civilians

In a circular issued at the end of April by the General Staff of the Kenya Army, the military announced that the SLDF had been responsible for the killing of over 600 people.[51] The NGO WKHRW documented 615 people killed by the SLDF up to February 2008, the vast majority of them civilians. According to WKHRW research, the rebel militia also abducted 118 and maimed 33 people.[52] A February 2008 police operation uncovered mass graves in the forest of Mt. Elgon, whom the police said were victims of the SLDF.[53]

Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of family members who described how their relatives were abducted by the SLDF over the last two years and never seen again. One woman described how her husband was taken from their house at night. Two days later her brother-in-law returned the bloodstained clothes her husband had been wearing when he was kidnapped, with one word: "sorry."[54]

Some persons were killed because of land disputes. A local area chief listed the names of other chiefs allegedly killed by the SLDF in 2006 because they supported the eviction of SLDF sympathizers from land earmarked by the government for others. They were Shiem Chemony Chesowo, an assistant chief, and Cleofas Sonit, a chief, both from an area within Mt.Elgon district.[55] One man who had land coveted by the SLDF and which was eventually taken from him, described how he was abducted by the SLDF and tortured at one of their bases in the forest. There, he witnessed five corpses lying around the torture site.[56]

However, many of the more recent murder victims of the SLDF were politicians or party agents who competed against SLDF's favored candidates in the December 2007 elections. One chief in Mt.Elgon district described how the bodies of five people opposed to the favored candidates of SLDF in the general election were dumped in his area one morning with their throats cut.[57] A retired civil servant said that, "Many of my neighbors had houses burnt and some of them were killed because they supported the wrong candidates."[58] The SLDF militia on the rampage had a motto, "The MP should be one. The party is one."[59] Meaning that no other parties should contest in Mt.Elgon, leaving the area open for the ODM candidates supported by the SLDF.

Mutilation and Inhumane Treatment

Dozens of witnesses described to Human Rights Watch how members of the SLDF came to their homes at night, beat them and members of their family, then bound and blindfolded persons and abducted them. Some were beaten in their homes and had their ears cut off. The signature mutilation of the SLDF is to cut off the ears of those who do not obey their orders or do as they wish.

One described what happened to him when he was abducted by the SLDF:

I was woken up by a knocking at the door. I opened it and there were guns and torches staring at me. They rounded up my cows, beat me and stabbed me as we walked. When we reached the bush they tied me by my feet to a tree, my head hanging down. There were others hanging also. They beat me very badly and said, 'Choose: either surrender all your possessions including your land or you die now.' I told them to take it. They cut off my ear as a mark, then they made me eat it. I crawled home, I could not walk.[60]

Many of the young men were mutilated in 2007 because they refused to join the SLDF or because they supported political parties opposed to SLDF candidates. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than a dozen people who had had their ears cut off by the SLDF and women who were beaten by members of the SLDF searching for their husbands.[61] One man described how the SLDF beat his naked wife in front of him as a warning to him not to stand for the opposition ODM party in the upcoming elections; it had been rumored that he was considering standing as he was a former councilor, but he was not the favored SLDF candidate.[62] He was later abducted along with others and forced to pay a fine. During captivity he witnessed male prisoners forced to have sex with each other and people having their ears cut off. "They wanted me to see how others were being molested before me, as a warning."[63]

Rape and Sexual Violence

Many young men who did not join the SLDF fled the area, leaving their wives to tend their farms. Human Rights Watch heard credible reports of the frequent rape of women, including by multiple SLDF assailants. Two sworn statements submitted to WKHRW and seen by Human Rights Watch describe how up to five alleged members of the SLDF gang-raped two women in 2007 for hours.[64]

Although Human Rights Watch did not interview any women or girls who were victims of rape, both male and female residents of Mt. Elgon (who had lived under SLDF control) told Human Rights Watch that rape of men and women by members of the SLDF was routine during the last two years, but that many people were too scared to report violations to the police because the SLDF explicitly warned all their victims not to go to the police or seek hospital treatment. This assessment was confirmed by the staff of a Kenyan organization providing assistance to torture survivors, Mwatikho, which was, the director said, "overwhelmed," by survivors of torture and rape by the SLDF after the beginning of the military operation as residents felt relatively safe to come and report crimes.[65]

Destruction of Property, Theft of Land, and Livestock

Over 20 people described how their homes were set on fire and livestock, money, and land were taken by the SLDF at gunpoint. Some witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the motive appeared to have been theft, sometimes politics, and sometimes score-settling in land disputes.[66]

Many people now living in towns further down the mountain are destitute since their land and their livelihood have been taken away. One man whose land was stolen, explained to Human Rights Watch: "I have the title deed, but the SLDF have guns. Now they have my land. I live in a shack in the town and my family and I eat the tomatoes that fall in the market."[67]

Individuals told how the SLDF always stole their cattle before they were abducted.[68] One woman described how SLDF militia broke into her home and demanded money, she gave it to them.[69] A man who was abducted by the SLDF gave them his phone and money so that he might keep his ear.[70]

Violent Politics and the Role of the SLDF in the 2007 General Election

The SLDF promoted its favored candidates in the 2007 general election in a vicious campaign that, according to local residents, amounted to a campaign of terror. The candidates favored by the SLDF were all contesting on an ODM ticket. A chief from the area told Human Rights Watch that the incumbent councilor for Emia ward, Nickson Manyu, was warned at gunpoint not to contest against the ODM candidate. He also reported widespread intimidation and electoral violence.[71] Retired civil servants, journalists, residents, and human rights groups described intimidation inside and outside polling stations including firing at polling stations.[72] The view of many was that the electoral commission was not fully in control of the elections in Mt.Elgon.[73]

Nearly all witnesses described SLDF interference on voting day. One man from Cheptais described the SLDF controlling polling stations, inking the fingers of voters while casting their ballots for them.[74] Forty-six polling stations up the mountain were transferred to the district headquarters in Kapsokwony because of insecurity. On voting day in Kapsokwony, one chief told Human Rights Watch that he saw armed SLDF militia patrolling in the town. "The town was surrounded by SLDF, they were scaring voters. I saw the SLDF boys voting five times [in one polling station]."[75]

Violations by Kenyan Security Forces

Too Much, Too Late

Nearly all residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch were initially supportive of the Kenyan joint police-military operation against the SLDF, but expressed serious misgivings about the way it was being carried out. They indicated that it had been a long time coming. Local human rights organizations Mwatikho and WKHRW, have repeatedly called for the government to tackle the SLDF problem since the beginning of 2007, a sentiment reflected by nearly all interviewees.[76]

Throughout 2007, the police, General Service Unit (riot police), and Anti Stock-Theft Unit conducted some operations against the SLDF but they were sporadic and not sustained. They were marred by allegations of human rights abuses, including beatings, burning of houses, and attacks on villages viewed as supporting the SLDF.[77]

The army first became involved in July 2007 although the military presence in Mt.Elgon was not publicly acknowledged by the authorities.[78] A senior government official told Human Rights Watch that operations were low level, because, "we feared politicizing the issue. You know SLDF and [local politicians] were closely related." Foreign diplomats were briefed along similar lines.[79]

However, once the December 2007 elections were completed, the government apparently felt unconstrained by political considerations and launched Operation Okoa Maisha (Operation Save Lives). The operation is supposedly a police-led joint operation comprising forces from the Kenyan army, General Service Unit (riot police), Administration Police, and regular police. However, officials have not so far been clear or consistent about who is actually in charge of day to day operations on the ground. There were numerous reports of the security forces committing unlawful killings, arbitrary mass detentions, systematic beatings and torture, and the enforced disappearances of dozens of people taken into the custody. As a man who had been beaten while farming in his field, taken to Kapkota military camp,[80] and then released, said, "Are they saving our lives or destroying our lives?"[81]

Unlawful Killings and Enforced Disappearances

The government's principal strategy to flush out the SLDF in Mt.Elgon has been to arrest all adult and teenage males (some as young as 10) in the area, and "screen" them at several camps including the Kapkota military camp in Cheptais division. At the time of arrest, and later in detention at Kapkota, detainees were routinely beaten by security personnel, and some died as a result. Others have not reappeared since being detained and are feared to have "disappeared." According to press reports, many children are also in detention.[82] A report by the visiting justice officer for Bungoma High Court put the figure at 32 school-age children in detention on May 21, 2008.[83]

In the mortuaries of Webuye and Bungoma in districts neighboringMt.Elgon, Human Rights Watch saw the bodies of five men brought by police from Mt.Elgon over the previous 14 days. Mortuary attendants say the police told them they came from the camp at Kapkota.[84] The bodies showed obvious visible signs of torture such as welts, bruising, swollen faces, broken wrists, and rope burns around the wrists.

As of April 2, 2008, 13 such bodies had been delivered to the mortuaries, and three of the victims were identified and collected. In those cases, in order for the hospital to release the body without a post-mortem, police told relatives to sign an affidavit stating, "that I or the relatives do not intend to lodge claim of any nature against anyone or the state pertaining the death of the said, X [name of deceased]."[85] Relatives who collected two of the bodies told Human Rights Watch the men had been arrested by the military several weeks before.[86] When the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights visited Bungoma mortuary several weeks later, technicians there showed them 20 bodies that had been delivered by the police and remained unidentified.[87]

Dozens of women described to Human Rights Watch how during several weeks in March their husbands and male relatives had been taken by soldiers or police at dawn. The women are now searching prisons, police stations, and mortuaries for the missing men. One widow who found her husband in Webuye mortuary two weeks after he had been abducted by the army, complained: "Before the security operation, male residents of Mt.Elgon fled the district for fear of forceful recruitment into the SLDF. Now they have either been rounded up or they have fled again, for fear of being tortured. Mt.Elgon is a mountain of women, all the men have gone."[88]

As of June 3, WKHRW has compiled a list of 72 missing people whom it says are confirmed dead, and a further 34 missing whose relatives could not confirm whether they were alive or not.[89] The military and police spokesmen continue to maintain in public that no one has died and no one has been tortured. Meanwhile, a source within the operation claimed that as of the end of April, 184 known SLDF suspects had been "disappeared" by the army and police (and this figure had reportedly risen to 220 by the end of June.)[90]

One woman told Human Rights Watch how her uncle was taken by the military at night at the beginning of March. Two days later, a relative told her that he had been killed by the army. Two days after that, his body showed up in the mortuary at Webuye. She collected the body and buried him. One of the security personnel present at his arrest apologized to her at the funeral.[91]

Dumping of Bodies

The Daily Nation newspaper on March 27, 2008 quoted a military source describing how bodies had been dumped in the forest reserve in Mt.Elgon national park.[92] In addition, a different military source told Human Rights Watch that eight bodies from Kapkota were flown in two helicopters and dumped in the forest, north of Kaptaboi village on April 2.[93] A former detainee from Kapkota told the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights that a helicopter was always kept on standby at Kapkota to ferry bodies to the forest.[94] Children interviewed by Associated Press described how they were forced to help load bodies of victims of torture onto military helicopters in Kapkota camp.[95]

A resident of Kaptaboi village interviewed by Human Rights Watch described seeing a military helicopter dropping off bodies on April 2:

We ran away from Kaptaboi where the military were conducting operations. We ran to the forest. There we stumbled across other soldiers. I was about 10 meters away, a helicopter landed and four soldiers dragged four bodies out of the helicopter and then threw them in the bush. Then they left, very fast.[96]

When asked about these reports, a senior government official told Human Rights Watch, "We take no responsibility for those killed in the forest. What are they doing in the forest anyway?"[97]

Arbitrary Arrest and Detention, and Torture

Dozens of men interviewed by Human Rights Watch described how military and police officers arrested them in their homes, on the street, in their fields. The soldiers asked them to show them members of the SLDF or the whereabouts of illegal weapons, and when they said they did not know, they were beaten. According to a man arrested in Cheptais trading center on March 14, 2008: "Soldiers came into my home and started beating me, they were shouting, 'Show us the criminals! Show us the criminals!'"[98]

Another person who was arrested in Cheptais on the same day explained:

It was , the soldiers banged on the door. They took me and others to the market place and made us lie down on the road while some of them beat us and others went to collect more men. Then they took us to Kapkota. There were many people there, maybe 1,000, it was all the men of Cheptais. There were many soldiers, kicking, beating with sticks. They made us lie down, they walked on top of us. Then they made us walk past a Land Rover with black windows. Those inside were the ones condemning or releasing us. The guilty ones had to stand in the 'red' line, the innocent ones, like me, went to the 'blue line.'[99]

Eyewitnesses described to Human Rights Watch men being beaten to death at Kapkota. One former detainee said "they [the military] were telling us, if one dies, just drag him off to one side."[100] Another saw officers holding apart the legs of a man while another soldier took a club to his genitals; two corpses lay nearby on the ground.[101]

Those in the red line were then taken to the jails at Bungoma and Kakamega. The army spokesman says around 750 of them have been charged.[102] As of April 2008, Bungoma prison was holding more than 400 persons brought from Mt.Elgon as a result of the security operation.[103] The government-appointed visiting justice officer to the prison told Human Rights Watch that all of those from Mt.Elgon had been tortured; many had urinal problems and fractures as a result; and 32 of them were in a critical condition and needed urgent medical attention. One died on April 2, four others died later in the month.[104]

A doctor working with Mwatikho Torture Survivors Organization was

denied entry to the prison in the presence of Human Rights Watch on March 31. Several weeks later in April 2008, a team from the human rights organization, Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU) gained access to Bungoma. What they found was shocking.

Bungoma prison was then holding a "staggering" 1,380 prisoners while its official capacity is 400.[105] The IMLU investigations also revealed that the prison authorities had turned away 40 further suspects from Mt.Elgon because of overcrowding. The men were taken to Webuye police station instead. IMLU interviewed 119 prisoners selected at random representing about 30% of the total of 400 detained at Bungoma prison. All of those interviewed had been tortured, with recurring patterns of injuries to the genitals, legs, back, and upper body.[106] These injuries are similar to those described by former detainees of Kapkota who were interviewed by Human Rights Watch.[107]

All of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch described systematic torture, affecting every single person picked up by the military-police operation and taken to Kapkota. These accounts were from groups of victims interviewed separately, of different ethnicities and in multiple locations, who were detained on different days throughout March 2008. IMLU concluded that 100 percent of those who had passed through Kapkota had been tortured.[108] According to the military's own figures, 3,818 suspects had been arrested between March 1 and April 29, 2008.[109]Later, in June 2008, the spokesman claimed the operation had arrested 3, 779.[110]

Further indication of the operation's widespread and systematic use of torture against Mt.Elgon detainees is shown by the figures of the Kenya Red Cross which reported that, as early as March 25, they had treated 1,400 people with injuries related to the operation during its first three weeks.[111] Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) also reported that, "between March 10 and April 14 MSF teams treated 252 victims of intentional trauma."[112]

Rape and Sexual Violence

Residents have been complaining of rape by security forces throughout the counter insurgency operations of 2007 and 2008.[113] A Kenyan legal organization warned about rape as early as April 2007, estimating that three women a day were being raped by security forces in Mt.Elgon.[114] At the beginning of the post-electoral violence in January 2008, several women complained of rape by GSU police.[115]

The actual number of rape cases documented in detail is low. However, human rights and women's rights activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch claim that rape is common and widespread. There are significant social barriers to gathering reliable information; women often fail to report violations to the police or local authorities, since they are viewed as perpetrators.[116]The only independent clinics in the area are operated by MSF who reported an increase in rape cases treated in their clinics as a direct consequence of the security operation, although they did not provide statistics.[117]

A woman described to Human Rights Watch the rape of her neighbor by security forces in March 2008: "At night [the officers] steal food, destroy homes and rape women. I heard a commotion next door. I woke up and came outside. I hid in the bushes. I saw my neighbor there on the ground outside her house. Three soldiers all took their turn."[118]

The Kenya National Commission of Human Rights noted only one case of a 14-year-old girl allegedly raped by police who had reported the matter in February 2007.[119]

Destruction of Property

Several residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch complained of the destruction of their homes by security forces in recent months, both before and during the recent operation. Police appear to commit the attacks to punish villages they believe are supporting the SLDF. International NGO staff also described widespread destruction of homes across the district.[120] A mother of four from Mt.Elgon district described how the security forces came to her village throughout October and December 2007 looking for SLDF members. "They had a list of SLDF suspects, but they did not follow the list, they just burnt all the houses, there was no pattern to it."[121] Another woman whose house was burnt in December 2007, just before the election said, "the police burnt ours because they thought we were janjaweed.[122] If you take things out of the house then they throw them back on the fire."[123]

Who is Responsible?

According to the military, the operation Okoa Maisha is "a police operation involving the regular police, administration police, anti-stock theft unit and aided by the military."[124] In the press, government spokesmen refer to the operation as a "joint police-military operation." The Department of Defence spokesmen repeatedly refused to meet with Human Rights Watch and referred researchers to the police claiming that the police are in the lead. [125]

These statements were matched by District Commissioner for Mt.Elgon, Birik Mohammed, who assured Human Rights Watch that the police were in charge.[126] However, the reality appears to be that in the area of operations the military are running things. When asked about the allegations of torture at Kapkota camp the District Commissioner immediately referred Human Rights Watch to the military command at Malakisi rather than the police, saying that the camp and surrounding area was under the military's control. Dozens of victims and witnesses who passed through Kapkota described being arrested by men in military uniform and transported in military trucks to Kapkota where soldiers beat them and asked them questions. Many people used the Swahili word "jeshi" meaning specifically army soldier, and not the word "askari" meaning any armed guard, whether police or military. The police normally wear blue uniforms. Riot police wear military fatigues but with distinctive red berets. Witnesses described to Human Rights Watch being apprehended by men in full military fatigues, not wearing red berets of the GSU, but the black and navy berets of the army.[127]

The army has said in private to western diplomats that its battalions were deployed on combat operations in the forest reserve and to provide security to police units conducting cordon and search operations in the villages lower down the mountain, the implication being that they were not in charge of detainees. However, an intelligence officer working with the military told Human Rights Watch that army and police officers were working hand in hand rounding up and torturing suspects. Many police were present at Kapkota, he reported, but were dressed in military uniform and taking orders from the military commander. He himself took his orders from the military commanders at Kapkota and Chepkube, where he said the military are firmly in control. According to him, orders pass directly from Nairobi to the military commander or via the Provincial Commissioner, but always to the military commander as effective head of the operation on the ground.[128]

The police spokesman for the operation similarly claimed that although it was a joint operation in which the Provincial Commissioner was in overall command, "the military provide logistics, but of course in Kenya the military is superior to the police."[129]

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch and those who recorded statements to IMLU lawyers were explicit in clearly differentiating between military, GSU, and other police units, based on their distinctive berets, and in identifying military officers as perpetrators of abuse. Human Rights Watch spoke to dozens of victims who were tortured inside military trucks. The report of the visiting justice officer in Bungoma jail describes victims being hung from army helicopters while flying.[130]

According to the IMLU investigation:

Virtually all the survivors were tortured by military officers but a few confessed to having been also tortured by police officers from the Kenya Police Service, Administration Police, and General Service Unit at the point of arrest or while being transferred to police stations or law courts…All the survivors identified Kapkota Military Camp as the main place where torture took place.[131]

In discussing the role of the police, IMLU found that:

The torture survivors indicated that police officers assisted the military in arresting the torture survivors and victims and in transferring them to waiting military vehicles and Kapkota military camp where they were tortured. Police also waited and picked torture survivors from the camp and transferred them to the police station, brought them back to Kapkota for further torture or took them to court. The survivors also pointed out that police also provided their vehicles to be used in ferrying survivors from one place to another.[132]

The army is clearly the most influential player in the joint operation, the one in charge of combat operations, and the principal supplier of logistics in terms of trucks, jeeps, arms, and helicopters. The available information points towards a chain of command in which the police and military are not only both fully aware of what is going on, but are actively adopting tactics that violate Kenyan and international human rights and humanitarian law. As a senior government official involved in the operation put it to Human Rights Watch:

This is how counter-insurgency is done. This is how the British did it during Mau Mau. This is what the Americans and the British are doing in Iraq and Afghanistan. Tell me how we should do it differently? In a cordon and search operation like this one you might have to detain everyone to get at the ones you want and if you try and detain a large hostile population, you might have to use force. One must first of all subdue those you want to question.[133]

While international humanitarian law provides armed forces leeway to temporarily detain civilians for security reasons during military operations, conducting mass arrests without legal basis and mistreating those in custody is prohibited at all times.

The military has consistently denied the claims of torture and suggested to concerned Western diplomats and Kenyan human rights organizations that "paramilitary units" of the police were responsible for the abuses. Even if such claims were true, commanders responsible for the operation would still ultimately be accountable for serious abuses. Those commanders include police, civilian, and military personnel.

The Kenyan civilian and military officials with authority for the security forces operating in Mt.Elgon include Minister of Internal Security George Saitoti, who is in overall charge of the police, Police Commissioner Hussein Ali, and the Administration Police Commandant, Kinuthia Mbuguathe. Those in charge of the army include the Minister of Defence Yusuf Haji, Chief of General Staff Jeremiah Kianga, and Kenya Army Commander Augustino Njoroge. The two men officially in charge of the operation on the ground are the Western Provincial Commissioner, Abdul Mwasserah, and the commander of the army in Mt.Elgon, S.K. Boiwo. All of these men should be subject to an independent investigation into the chain of command in the joint operation in Mt. Elgon to establish how much was known about the nature of the systematic torture, at what level, and what steps were taken to prevent it.

Applicable Law

International Human Rights Law

International human rights law is applicable to the situation in Mt.Elgon, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[134] the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,[135] and the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights.[136]

The Convention against Torture defines torture as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person by, or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity." In order to amount to torture, such pain must be inflicted for specific reasons, including extracting information or a confession, punishment, or intimidation.[137]

The Kenyan government has a legal obligation to carry out prompt and fair investigations into torture and prosecute and punish military and civilian officials responsible.[138]All states party to the Convention against Torture are responsible for bringing torturers to justice.[139] The UN Committee against Torture has stated clearly that perpetrators of torture should not be granted amnesty.[140]

A full investigation into torture should trace the orders that led to the torture, back to those who gave them, whether civilian or military commanders. [141] But the investigation should also identify those who are responsible under command responsibility, that is, those who knew or should have known about the abuses, and were in position of command yet failed to prevent the abuses, or punish those responsible. The Committee against Torture has stated that it:

considers it essential that the responsibility of any superior officials, whether for direct instigation or encouragement of torture or ill-treatment or for consent or acquiescence therein, be fully investigated through competent, independent and impartial prosecutorial and judicial authorities.[142]

Kenya has incorporated many of the provisions of the most important human rights treaties in its constitution and other relevant national legislation.[143] These provisions prohibit violations of the right to life, torture, and other inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary arrest and detention, and unfair trials. They also provide for the rights to the protection of the home and family, and specific protection of children in times of armed conflict.[144]

International Humanitarian Law

Although the situation in Mt.Elgon may have initially been a police operation, since the Kenyan army began actively participating in operations against the SLDF in Mt.Elgon in March 2008, fighting has risen to the level of an armed conflict under international humanitarian law (the laws of war). The operation to contain the SLDF has altered not only due to the deployment of Kenyan armed forces, but because of the intensification of clashes and the use of heavy weaponry against areas under SLDF control.

Both the Kenyan security forces and the SLDF are obligated to observe article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 (common article 3), the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II), applicable to non-international armed conflicts, and relevant customary international law. Kenya is a party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Protocol II.[145]

International humanitarian law forbids the deliberate harming of civilians and other persons not (or no longer) taking part in the hostilities, including wounded or captured combatants. It also provides rules on the conduct of hostilities to minimize unnecessary suffering.

A fundamental principle of international humanitarian law is that parties to a conflict must distinguish between combatants and civilians, and may not deliberately target civilians or civilian objects. Protocol II states that "the civilian population and individual civilians shall enjoy general protection against the dangers arising from military operations."[146] They are not to be the object of attack, and all acts or threats of violence with the primary purpose to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited.[147]

Summary or extrajudicial executions and the mistreatment of detained persons are illegal under any circumstances according to both international humanitarian and human rights law. Common article 3 prohibits "at any time and in any place whatsoever" with respect to civilians and captured combatants:

(a) Violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment, and torture;

(b) Taking of hostages;

(c) Outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment;

(d) The passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of international humanitarian law, including the mistreatment of persons in custody and deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian property when committed with criminal intent, amount to war crimes. Criminal intent requires purposeful or reckless action. Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime. Responsibility may also fall on persons ordering, planning, or instigating the commission of a war crime.[148] Commanders and civilian leaders may also be prosecuted for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.[149]

Under international law, Kenya has an obligation to investigate alleged war crimes by their nationals, including members of their armed forces, and prosecute those responsible for war crimes.[150] Should the Kenyan government fail to fairly and credibly investigate and prosecute those responsible for war crimes, the crimes may fall within the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Kenya ratified the Rome Statute of the ICC on March 15, 2005.

The Response of the Kenyan Government

The fact that the government has finally taken the SLDF abuses seriously after several years of inaction is an important development. In April 2007, the crisis prompted the Parliamentary Committee on Administration and National Security to summon then-Internal Security Minister John Michuki to discuss the government's response.[151] Even then, the director of police operations told journalists that there was no such thing as the SLDF and that, "the fighting in Mt.Elgon was sparked by land disputes between two clans."[152]

The problem, however, is the serious human rights violations that have accompanied the clampdown. The main difference between the half-hearted security operations in 2007 and the 2008 joint police-military operation is one of scale. The actions of security forces in 2007 were heavy-handed but the 2008 operation much more so. Coupled with the military deployment, helicopters, and heavier firepower, there has been tighter control on access to the area for journalists, humanitarian workers, and human rights investigators. The military appears to be afraid of scrutiny, with good reason.

The operation has led to the arrest of some of the well-known leaders of the SLDF, and the disruption of their activities. However, even as evidence has piled up-human rights groups have interviewed hundreds of victims-the government persists in denying that anyone has been tortured as a result of the security operation. In response to the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights' May 2008 report of torture, the third major report on the subject, which followed Human Rights Watch's April 4 press release, and IMLU's investigation of the same month, the military spokesman Bogita Onyeri still claimed that the military had harmed no one in the course of the operation.[153] Even once an internal investigation was underway, the spokesman told Human Rights Watch that, "no torture has taken place."[154] The repeated denials of torture by the security forces, especially in the face of tacit acknowledgement by senior government officials off the record, rings increasingly hollow. As a recent editorial in The Standard newspaper put it:

Operation Okoa Maisha, has all the hallmarks of other lawless State clampdowns of recent times….Following the ruthless crackdown on suspected Mungiki sect members in June last year, an operation that resulted in hundreds of unexplained illegal killings, Government claims of respect for law and human rights are not convincing.[155]

Eventually, the authorities announced an internal investigation by the police into the allegations of torture on June 5, 2008[156] but without specifying the terms of reference, the nature or time frame of the investigation, or who would be conducting it. To meet its legal requirements in investigating torture, any investigation should be independent, transparent, and should involve participation from the Kenya National Commission of Human Rights since such crimes fall squarely within its mandate. An internal investigation conducted by the same security forces accused of crimes and reporting to senior commanders and government ministers who should in any case themselves be the subject of investigation will lack credibility.

There has been a debate for some time in Kenya about the need for a Police Oversight Board to impartially and independently investigate the conduct of the police where allegations of misconduct or criminality arise. The need for independent oversight of the security forces, including the military is greater than ever. Not least because it will help the forces themselves to restore public confidence by demonstrating that they are transparently addressing public concerns.

Success?

The military argues that Operation Okoa Maisha has so far been a success. In a circular, the representative of the Chief of the General Staff cited the recovery of 51 AK47 rifles and three grenades as evidence of "a large number of lethal weapons recovered."[157] Given that human rights organizations estimate the numbers of AK47s circulating on the mountain as in the tens of thousands, this indicator of success is clearly questionable.[158] A more noteworthy indicator might be the 758 suspects arraigned in court on charges of "promoting war-like activities."[159] However, the true test of the success of the operation will be whether or not it succeeds in ending the SLDF's abuses and whether the state can secure convictions against those individuals who are responsible for the violence and for funding, organizing, and otherwise supporting the SLDF's activities. According to human rights organizations, many of those 758 suspects initially detained have since been released on bail.[160]

The widespread use of torture not only has serious moral and legal implications for the Kenyan security forces, and for public trust in the state, it will also likely undermine their effort to secure prosecutions. The use of confessions or testimony elicited after torture is not only legally inadmissible where used against a defendant, such information is also generally considered to be of extremely poor quality given that individuals will often provide false information simply to end the abuse.

Humanitarian Access to Detainees

Since the operation started in March 2008, access for medical staff to the prison and military camps being used as ad hoc detention centers has been erratic. Initially there was no access except for occasional visits by nurses from the Kenyan Red Cross. Nearly one month later, in late April 2008, IMLU were allowed in and arranged some belated consultations. The issue of medical access is urgent given that prisoners have been seriously tortured-five have died in custody so far-and Bungoma prison has been overcrowded at four times its capacity.[161] The visiting justice officer was told by the prison director that they had allowed the Kenya Red Cross to come and treat some of the wounded.[162] However, the Kenya Red Cross team did not include a doctor.

At present, although the Kenyan Red Cross has had some access to detention centers, the International Committee of the Red Cross has not. As such, there is no international, independent monitoring of the treatment and conditions of those detained in the course of the military operation. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights has the mandate to visit and inspect all detention facilities. However, Kapkota and the other military camps in Mt. Elgon district are not gazetted as detention centers, and thus the KNCHR does not have the right to visit, being denied the opportunity when they requested it in the course of their research in April 2008. In its report the Commission called for an end to detention at un-gazetted locations because it was an impediment to the mandate of the KNCHR to protect the rights of Kenyans and thus, by implication, a further violation of human rights under Kenyan law.[163]

The Kenyan authorities should allow medical personnel immediate access to detainees in prisons and military bases where hundreds of people have been tortured, some of whom still require urgent medical attention.

Harassment of Human Rights Defenders

The security forces have targeted human rights defenders who attempt to expose what is happening in the security operation. Two leading human rights activists working with Human Rights Watch were sought by the military following their efforts to expose human rights violations by the military in Mt.Elgon. They have since filed complaints with the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Taiga Wanyanja of Mwatikho Torture Survivors Organization went into hiding after the publication of the April 4 joint statement with Human Rights Watch. Military officers went to his parents' home demanding to know where he was. Others went to his office on several occasions and asked the secretary to reveal his whereabouts. She did not know.[164] Military officers also pursued Job Bwonya of WKHRW who was co-signatory to the press release of April 4. They visited two WKHRW monitors, one in Lwandanyi and the other in Sirisia demanding to know his whereabouts. Other security personnel then visited the offices of WKHRW in Bungoma repeatedly looking for him. The staff eventually abandoned the office. Taiga Wanyanja and Job Bwonya left the country for a short time.[165]