Vigilio Mirano didn’t stand a chance. On Sept. 27, 2016, Mirano received a letter from local government officials in the Manila slum where he lived with his wife and two children implicating him as a drug user and ordering him to appear at a “mass surrender” ceremony on Sept. 30.

Hours later, four armed men dressed in black and wearing face masks burst into his home, dragged him into the outside alley and shot him six times in full view of his horrified family. The killers then drove away unimpeded through a nearby police checkpoint. A police report stated that Mirano had drawn a gun on anti-drug police and died in an “exchange of gunfire.” Witnesses call that account false.

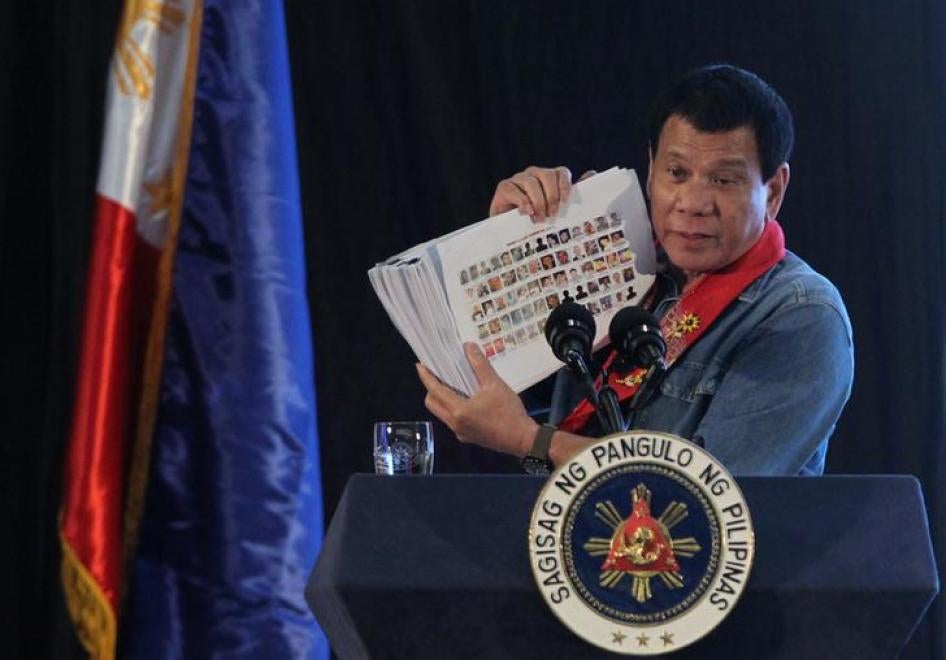

Mirano is a victim of the “war on drugs” declared by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and which Philippine national police personnel and “unidentified gunmen” have mostly waged in Manila’s poorest areas. Duterte’s drug-war foot soldiers have been chillingly efficient: the anti-drug campaign’s death toll surpassed 7,000 at the end of January when the police stopped issuing weekly updated kill statistics.

Duterte has consistently justified the 2,555 killings acknowledged by the police between July 1, 2016 and Jan. 31, as a legitimate police response to armed suspects who “fought back.” Duterte’s government has repeatedly dismissed allegations that the police have deployed “death squads” in a campaign of summary killings under the guise of anti-drug operations.

But research by Human Rights Watch into the death of Mirano and 31 other individuals killed since Duterte’s election exposes the government’s narrative of its drug war as a blatant falsehood. Interviews with witnesses to killings, relatives of victims and analysis of police records expose a damning pattern of unlawful police conduct designed to paint a veneer of legality over summary executions.

While the Philippine national police have publicly sought to distinguish between suspects killed while resisting arrest and killings by “unknown gunmen” or “vigilantes,” Human Rights Watch found no such distinction in the cases investigated. In several cases, the police dismissed allegations of involvement and instead classified such killings as “found bodies” or “deaths under investigation” when only hours before the suspects had been in police custody. Such cases call into question government assertions that the majority of killings were carried out by vigilantes or rival drug gangs.

The cases analyzed by Human Rights Watch showed planning and coordination by the police and in some cases local civilian officials. These killings were not carried out by “rogue” officers or by “vigilantes” operating separately from the authorities. Research indicates that police involvement in the killings of drug suspects extends far beyond the officially acknowledged cases of police killings in “buy-bust” operations.

Efforts to get accountability for drug-war deaths have gone nowhere. Philippine national police Director-General Ronaldo Dela Rosa has slammed calls for a thorough and impartial probe of the killings as “legal harassment” and said it “dampens the morale” of police officers. Duterte and some of his key ministers have praised the killings as proof of the “success” of the anti-drug campaign. Duterte and Secretary of Justice Vitaliano Aguirre III have justified the trashing of the rule of law and due legal process for “drug personalities” by questioning the humanity of suspected drug users and drug dealers. On Feb. 24 police arrested the highest profile critic of the drug war, Senator Leila de Lima, on politically motivated drug charges following a relentless government campaign of harassment and intimidation because of her outspoken criticism of Duterte’s “war on drugs” and her demands for accountability.

As the death toll rises, even after an official suspension of police anti-drug operations in January following revelations of the brutal killing of a South Korean businessman by alleged anti-drug police, it’s clear that the Philippine government has no intention to investigate these unlawful killings.

That’s why Human Rights Watch is calling on the United Nations to establish an independent international investigation into the killings. Duterte’s repeated calls for anti-drug killings could constitute acts instigating law enforcement to commit murder. His statements encouraging vigilantes could constitute incitement to violence. Duterte, senior officials, and others implicated in unlawful killings could be held liable for crimes against humanity committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population.

The killing of Vigilio Mirano and thousands of other victims of Duterte’s drug war calls for an urgent international response. Turning a blind eye to these crimes will merely ensure that such abuses continue.