Rudy lay on the back seat of the taxi, struggling to breathe. As the car sped through the streets of San Miguel, in eastern El Salvador, he clutched his stomach and felt something fleshy. “The top of my pancreas was hanging out. I couldn’t stand the pain,” he said.

Gunned down in a crowded street in broad daylight, Rudy, 16, had become the latest victim of the terrifying gang violence that is menacing Central America.

Rudy knows who tried to kill him, and why. Days earlier, he had received a phone call from a local gang leader who ordered him to become a member. “But I’ve never wanted to be part of that,” Rudy said. “I told them, ‘No, I am a humble person.’” The gang leader gave Rudy three days to change his mind or die.

Rudy’s experience is not unique. In a new report, Human Rights Watch found that children as young as 11 are increasingly being targeted by gangs in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Some are forced to join; others are murdered. A surge of mob violence in the region over the past decade has prompted thousands of children to flee for the relative safety of Mexico. But there, they face a tough time, too. Authorities lock up many of them for breaching immigration rules and make applying for asylum extremely difficult.

By the time the gang members who threated Rudy came to his house, he had already fled. But a few days later, Rudy bumped into the gang at a bus stop. As a gang member walked toward him, drawing a weapon from inside his shirt, Rudy froze. “My brain stopped working. The mind is like that, it stops like a computer.”

Struck by a bullet, Rudy fell to the ground and briefly lost consciousness. He managed to stagger to his feet and began to run.

The gang gave chase, shooting wildly. A woman nearby, who was trying to usher her young children to safety in a house, was hit in the arm by a stray bullet. Eventually one of Rudy’s neighbors, alerted by the commotion, emerged from his home and fired a single shot into the air. It was enough to stop the gang, and Rudy was able to stagger away.

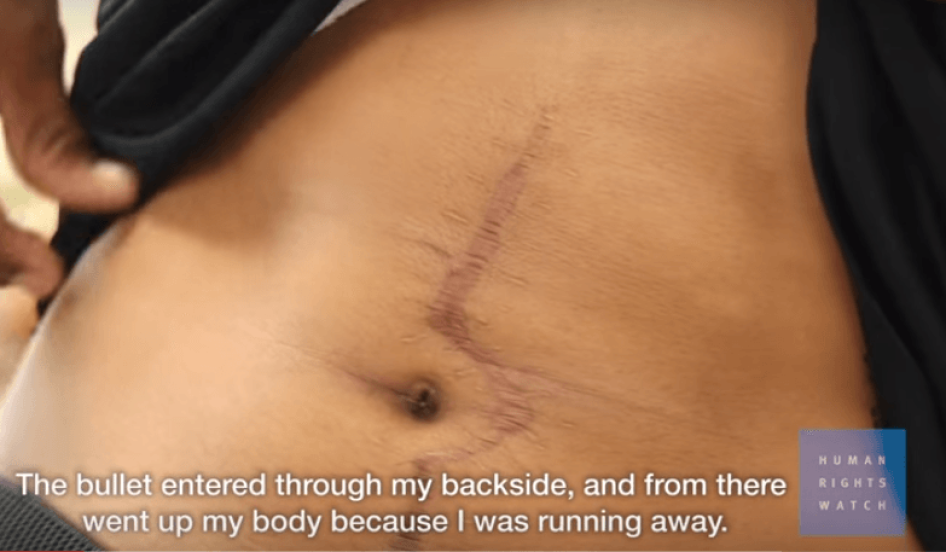

Bystanders bundled him into a passing cab and rushed him to hospital, where surgeons found that the bullet had entered through his buttock and traveled up through his abdomen, splitting his pancreas open.

Rudy was in a coma for three days. When he awoke, his mother was at his bedside, crying. Doctors told her they almost “lost” Rudy several times during surgery and had to revive him with a defibrillator.

Rudy lay in bed, listening to doctors explain how they pieced his stomach together. He was still in extreme pain, but his main emotion was overwhelming sadness. He knew the gang would track him down and try to finish him off, and that his life as he knew it – studying in the mornings and working at a supermarket in the afternoons – was over. “I cried because I had lost my job and my education.”

Rudy spent a month in hospital recuperating, but his home no longer felt safe. He moved from one neighborhood to another in the following weeks, trying to elude the gang.

One day, Rudy’s mother called him to say the gang members had visited the family home and delivered a chilling message.

“They told my mother that they were going to cut me into pieces,” he told Human Rights Watch.

This was no hollow threat. “There was a boy from my community,” he said. “The gang cut him up into pieces and left his remains scattered about the neighborhood. They left parts of the boy all over. Hands, everything.”

Rudy’s fear was all-consuming. “I couldn’t sleep. Their faces were always on my mind. I dreamed they would come and do the same to me.”

The gang’s threats had forced Rudy’s brother, his uncle, and his aunt into hiding; now it was Rudy’s turn to flee. His brother and uncle left with him.

The journey out of El Salvador was long and dangerous. Traveling by bus and on foot, they crossed through Honduras and Guatemala to reach Mexico. At one point, bandits held the trio up at gunpoint and stole their remaining cash, including the last dollars hidden in their underwear. They trekked through forests, trying to evade the authorities, and begged locals for food and spare clothing when they could. Eventually, they hitched a ride on a train and made it to Ixtepec, where Rudy and his relatives remain today.

But, like scores of others have found, making it to Mexico didn’t end Rudy’s ordeal. He is still waiting for a humanitarian visa, which would allow him to stay and work in the country for one year and decide what to do next, without the fear of being locked up. In the meantime, he lives in a legal limbo.

Human Rights Watch has found that authorities in Mexico often lock up asylum seekers fleeing gang violence – including unaccompanied children – in immigration detention centers, where they can languish for months in miserable conditions. Immigration officials tell children that they have little chance of being granted asylum, so many accept deportation back to their home countries, despite the enormous risk of being killed if they do so. Less than 1 percent of children who make it to Mexico are granted asylum or formal protection.

Like others in his position, Rudy’s goal is to make it to the United States – partly because he hopes to join relatives there, but also as he believes he has only a slim chance of being offered asylum in Mexico.

“My wish is to get to the other side,” he said.