Summary

Gang violence has plagued Central America’s “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras for more than a decade. Children are particularly targeted by gangs in these three countries. In Honduras, for example, over 400 children under age 18 were killed in the first half of 2014, most thought to be the victims of gang violence. Many more are pressured to join gangs, often under threat of harm or death to themselves or to family members. Girls face particular risk of sexual violence and assault by gang members.

As a result of these and other risks to their lives and safety, children have been leaving these three countries, on their own and with family members, for years. The story of Edgar V., age 17, indicates the perils they face.

“I left Honduras because of problems with the gang. They wanted me to join them, and I didn’t want to, so I had to flee,” Edgar told Human Rights Watch. The intimidation he faced at school was intense, and shortly after one of his classmates was killed for wearing a shirt of a color associated with a rival gang, Edgar stopped attending. Even though Edgar tried not to attract attention to himself, the gang continued to pressure him to join their ranks. “They came to my house and told me, ‘Join the gang,’” he said. “They hit me. They hit me and I fell to the ground. From then on, they didn’t hit me again, but they threatened my mother. They said they would kill me and my mother.”

His mother took him to the police station to make a complaint, and he took refuge for a time in a shelter run by missionaries. “I spent two months and 21 days there,” Edgar said. “I needed to be there for my protection, because they [the gang] were hunting for me. But I would have been there my entire life. I would lose the rest of my adolescence. I wouldn’t be able to study. I would become an adult and wouldn’t know anything. I told myself, ‘I can’t do this. I have to leave.’”

He estimates that it cost his family about US$1,000 for him to travel from Tegucigalpa to San Pedro Sula and then by bus to the border with Guatemala. “In Guatemala I stayed in a hotel one night and then took another bus. Then another hotel—I don’t remember the name of the town—and then another bus. I kept doing this.”

He made it as far as the Mexican state of Oaxaca. “I was on a bus in Oaxaca, and we reached a point where there were three or so immigration police on the road. They stopped the bus. They asked everybody, ‘Do you have papers? Where are you from?’ Those of us who said El Salvador or Honduras had to get off the bus.

“At the station, they asked me all these questions. They asked me if I came alone. Who gave me the money. All these things they asked me. How I crossed the border.

“I told the immigration official that I couldn’t return here,” Edgar said. He showed the official a copy of the complaint he and his mother had filed. “Then they said, ‘You know, you can ask for asylum.’ I said yes. But I was already locked up, and they said it would be a long time before I heard. I couldn’t handle that. At least two months, up to six months [longer in detention], just for the response.

“When they told me it would be six months before I heard back, I said no, I don’t want that. They sent me here,” he said, referring to the reception center in San Pedro Sula where he spoke to Human Rights Watch the day he was returned to Honduras.

Tens of thousands of children travel from Central America to Mexico each year, most from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. To be sure, many children migrate only for economic reasons and do not qualify for refugee status or other recognized forms of international protection from return to their countries of origin; these children may be returned to their home countries in a manner that complies with international and Mexican law.

But as many as half are fleeing threats to their lives and safety, meaning that they have plausible claims to international protection, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has estimated. As Edgar did, many of the children we spoke with told us that they fled to escape violence and pervasive insecurity. We heard accounts of children who left in search of safety, with or without their parents and other family members, after they or their families were pressured to join local gangs, threatened with sexual violence and exploitation, held for ransom, subjected to extortion, or suffered domestic violence. In some instances, children left after their grandparents or other elderly caregivers died, or left because they feared that there would be no one to care for them in their home countries when these relatives passed away.

By law, Mexico offers protection to refugees as well as to others who would face risks to their lives or safety if returned to their countries of origin. Mexican government data suggest, however, that less than 1 percent of children who are apprehended by Mexican immigration authorities are recognized as refugees or receive other formal protection in Mexico.

International standards call for a fair hearing on every claim for refugee recognition. Resolving claims by children requires an appreciation of child-specific bases for international protection—including, in the Central American context, the ways that children are targeted by gangs. Unaccompanied and separated children should receive legal representation and other assistance in making claims for refugee recognition.

Children should never be detained as a means of immigration control; international standards call on states to “expeditiously and completely cease the detention of children on the basis of their immigration status.” Compliance with this standard does not mean that Mexico must allow unaccompanied and separated children to roam freely throughout the country; to the contrary, Mexico has an obligation to provide these children with appropriate care and protection.

On paper, Mexican law and procedures reflect international standards in many respects. When agents of the National Institute of Migration (Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM), Mexico’s immigration agency, encounter children, INM’s child protection officers should screen them for possible protection needs. While Mexico’s Immigration Law requires the holding of adult migrants who are undocumented, it requires children to be transferred to shelters operated by Mexico’s child protection system, the National System for Integral Family Development (Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, DIF).

In addition, under Mexican law, any INM or other government official who receives a verbal or written request for asylum from a migrant of any age must forward the application to the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, COMAR), Mexico’s refugee agency. Children and adults who are not apprehended by INM agents and who instead submit applications for refugee recognition directly to COMAR are not detained while their applications are pending. Unaccompanied children, children and adults who apply for refugee recognition, and migrants of any age who are the victims of serious crime in Mexico can also apply to the INM for a humanitarian visa, a status that allows them to live and work in Mexico for one year, and which may be renewed indefinitely.

Human Rights Watch conducted multiple research missions in 2015 to examine how Mexico is applying its own and international law in its treatment of Central American migrants, particularly children. We spoke with 61 migrant children, more than 100 adults, and representatives of UNHCR and nongovernmental organizations. We were not able to meet with senior officials with INM’s enforcement department despite multiple requests for interviews, but we did meet with government officials with COMAR and DIF, senior INM officials in the agency’s regularization department, as well as the INM official in charge of the agency’s detention center in Acayucan, Veracruz.

Our research found wide discrepancies between Mexico’s law and the way it is enforced. Children who may have claims for refugee recognition confront multiple obstacles in applying for refugee recognition from the moment they are taken into custody by INM. As one UNHCR official told us, “the biggest problem in Mexico is not the [asylum] procedure itself, but access to the procedure.”

The first is the failure of INM agents to inform migrant children of their right to seek refugee recognition. A 2014 UNHCR study found that two-thirds of undocumented Central American children in Mexico are not informed of their rights by INM agents. We heard the same in our own interviews, and research by groups that work with asylum seekers and migrants, including the Fray Matías Human Rights Center, La 72, and Sin Fronteras, made similar findings. INM agents also do not as a rule inform children that they can seek humanitarian visas, as is likewise required by Mexican law.

The second is the failure of government authorities properly to screen child migrants to determine whether they may have viable refugee claims. INM agents, including INM child protection officers, rarely actively question children about their reasons for migrating. Proper screening of migrant children would reveal that many have valid claims for refugee recognition.

Third is the absence of legal or other assistance for most children who do apply for refugee recognition, unless they are fortunate enough to be represented by one of the handful of nongovernmental organizations that provide legal assistance to asylum seekers. The processes for determining applications are not designed with children in mind and are frequently confusing to them.

A fourth obstacle, perhaps the most daunting, is the practice of holding all child migrants in prison-like conditions. Although Mexican law provides that migrant children should be transferred to DIF custody and should be detained only in exceptional circumstances, detention of migrant children is the rule, according to our interviews and the findings of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, UNHCR, and nongovernmental organizations. Over 35,000 children were held in immigration detention centers in 2015; more than half of that total were unaccompanied. Even those children lucky enough to be handed over by INM agents to DIF shelters experienced a form of detention. Children in most DIF shelters do not attend local schools, are not taken on supervised visits to local playgrounds, parks, or churches, and do not have other interactions with the community; unless they need specialized medical care, they remain within the four walls of the shelter 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the duration of their stay.

Detention—never appropriate for children—is particularly problematic for those who want to apply for refugee recognition. Children report being told by INM agents that merely applying for recognition will result in protracted detention, either in INM-run facilities or in the virtual detention of DIF shelters, while their applications are considered. We heard from children and parents who decided not to apply or who withdrew applications because they did not want to remain locked up. Some children remained in immigration detention centers for a month or more, and those who exercise their right to appeal adverse decisions on their applications for refugee recognition might be held in immigration detention centers for six months or more.

These obstacles are serious barriers for children who have claims for refugee recognition. Where the indirect pressure on individuals is so intense that it leads them to believe that they have no access to the asylum process and no practical option but to return to countries where they face serious risk of persecution or threats to their lives and safety, these factors in combination may constitute constructive refoulement, in violation of international law.

Moreover, in cases where children have been targeted by gangs or reasonably fear that they will suffer violence or other human rights abuses in their countries of origin, their return is almost certainly not in their best interests. The same is true where family members in their countries of origin are unable or unwilling to care for the children. The return of children to their home countries under these circumstances breaches Mexico’s obligations to protect children and ensure that its actions are in their best interests.

We saw some good practices by Mexican officials. In northern Mexico, unaccompanied children appeared to be quickly and routinely housed in DIF-run shelters, rather than in INM-run detention centers. DIF officials in every part of Mexico we visited displayed a strong understanding of Mexico’s children’s rights law, and we heard of cases in which they had identified and referred children with possible international protection needs to COMAR. We heard other individual accounts of positive experiences with other Mexican officials—of one police officer who took a family to a migrant shelter, another who helped a 15-year-old boy who had been abandoned by the guide he had paid to take him through Mexico, an INM agent who meticulously advised a 17-year-old boy of his right to apply for refugee recognition.

Although such experiences are unfortunately not the norm for most children who come into contact with INM agents, these exceptions demonstrate that Mexico is capable of complying with its international obligations and the requirements of its own laws in the treatment of Central American children and adults who are fleeing violence in their home countries.

The United States government support for Mexico’s immigration enforcement capacity increased after mid-2014, when record numbers of Central American unaccompanied children and families with children arrived in the United States.

US Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson praised the Mexican government for taking “important steps to interdict the flow of illegal migrants from Central America bound for the United States.” If US policy objectives were to “interdict the flow” by shifting enforcement responsibilities to Mexican immigration authorities, as Secretary Johnson’s and other US officials’ remarks suggest, they were successful through the remainder of 2014 and much of 2015. US apprehensions of unaccompanied children from the Northern Triangle fell during this period while Mexican apprehensions rose, suggesting that the United States had effectively persuaded Mexico to take a greater role in immigration enforcement along its border with Guatemala.

Key Recommendations

To address the serious shortcomings identified in this report, Mexico should ensure that children have effective access to refugee recognition procedures, including by providing them with appropriate legal and other assistance in the preparation and presentation of applications. The government should expand the capacity of COMAR, the Mexican refugee agency, including by establishing a presence across Mexico’s southern border.

Mexico has a right to control its borders and to apprehend people who enter the country irregularly, including children. However, migrant children should in no circumstances be held in detention. Mexico should make greater use of alternatives to detention already available under Mexican law—in particular, by expanding the capacity of DIF shelters and by giving DIF discretion to place unaccompanied children in the most suitable facilities, including open institutions or community-based placements. To be sure, some children will need a greater degree of supervision and may well be need to be housed in closed facilities, but DIF should be empowered to identify, on a case-by-case basis, the housing arrangement that is most consistent with an individual child’s best interest.

Mexico can provide appropriate care and protection to unaccompanied and separated children in a variety of ways, whether by housing children with families or in state or privately run facilities. But locking children up in prison-like settings does not meet international standards.

The US government, which has pressured Mexico to interdict Central Americans and has spent considerable sums to enhance Mexico’s immigration enforcement capacity, should provide additional funding and support to improve and expand Mexico’s capacity to process asylum claims and to provide social support for asylum seekers and refugees. The US government should link funding of Mexican entities engaged in immigration and border control to their demonstrated compliance with national and international human rights standards and anti-corruption measures. And the US government should also expand its Central American Minors Program to allow children to apply from Mexico and other countries where they have sought safety, and to allow applications based on a relationship to extended family members, not only parents, in the United States.

Additional recommendations are set forth at the end of this report.

Glossary

Adolescent: As used in Mexican law, a child between the ages of 12 and 17.

Child: As used in this report and in international law, any person below the age of 18 years. Mexican law frequently uses the term “child” to refer to children under the age of 12.

COMAR: Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados), the government agency that adjudicates applications for refugee recognition and complementary protection.

Coyote: A slang term for a person who engages in the smuggling of migrants; such persons are also called polleros.

DIF: National System for Integral Family Development (Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia), Mexico’s child protection agency.

“Holding”: The official term (in Spanish, alojamiento) for the detention of a migrant.

Immigration station: The official term (in Spanish, estación migratoria) for an immigration detention center.

INM: The National Institute of Migration (Instituto Nacional de Migración), the government agency charged with enforcement of the immigration laws.

Mara: A slang term for gang, often used to refer to a group that controls a large area, undertakes a range of criminal operations, and has transnational links.

Mara 18:The 18th Street Gang (Barrio 18), one of the largest and most well-known of Central America’s gangs, with a presence in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the United States.

Mara Salvatrucha: Another large, well-known Central American gang; like the Mara 18, the Salvatrucha (sometimes referred to as the MS-13 or the 13) has a presence in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the United States.

Marero: A gang member.

MS-13: Another name for the Mara Salvatrucha.

OPI: Child protection officer (oficial de protección a la infancia), officials within the National Institute of Migration.

Pandilla: A gang, usually a loosely organized, local operation.

Pollero: A slang term for a person who engages in the smuggling of migrants.

“Presentation”: The official term (in Spanish, presentación) for the INM’s order for “holding” (alojamiento), or detention, of a migrant until his or her status is regularized or he or she is removed from Mexico.

Refugee: As used in this report, a person who has a well-founded fear of persecution because of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, who is outside of the country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return (the standard in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol) or have fled his or her country because his or her life, safety, or freedom has been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order (the standard in the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, which has been incorporated into Mexican law).

Separated child: A child who has been separated from both parents, or from the previous legal or customary primary caregiver, but not necessarily from other relatives.

Unaccompanied child: A child who has been separated from both parents and other relatives and is not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.

Zetas: A criminal syndicate based in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, said to be Mexico’s largest drug cartel, with operations along Mexico’s northern and southern borders and the states of Guerrero, Michoacán, Oaxaca, and Veracruz, along with Guatemala and parts of the United States.

Methods

This report is based on field research in Mexico and Honduras between April and December 2015. Human Rights Watch undertook field research in Mexico from April 24 to May 8, May 18 to 20, June 16 to July 2, August 25 to 30, October 19 to November 2, and November 29 to December 3, 2015, and field research in Honduras from May 9 to 17 and June 8 to 15, 2015. In the course of this investigation, Human Rights Watch researchers visited the Mexican states of Chiapas, Chihuahua, Oaxaca, Sonora, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz, as well as the Federal District, and, in Honduras, the cities of San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa.

Three Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed a total of 61 children (49 boys and 12 girls) between the ages of 11 and 17 who were refugees, asylum seekers, or migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Forty-six of the 61 were unaccompanied or separated children, meaning that they were not accompanied by parents or legal guardians but may have traveled from their countries of origin with siblings, other relatives, or partners close to their age. Sixteen children were asylum seekers at the time of our interview. Two other children had been denied recognition as refugees and were unsuccessful on administrative review. Two children, one of whom had been denied refugee recognition on administrative review and the other an asylum seeker, had received humanitarian visas. One had become eligible for regularization based on a relationship to a Mexican national, although she had not yet received a residence permit at the time of our interview. None of the children we spoke with had been recognized as refugees at the time we interviewed them.

Our researchers also interviewed over 100 adult refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, including some who were 18 or 19 years old at the time of our interview and recounted experiences they had had while still under the age of 18.

We interviewed most children and adults in shelters run by local entities of Mexico’s child protection system, the National System for Integral Family Development (Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, DIF), or civil society groups and, in Honduras, in the Edén reception center (now known as the Belén Attention Center) for children and families returned from Mexico. For several of our interviews in Honduras, we arranged to interview children in other locations they and their parents chose.

We entered one immigration detention center, in Acayucan, Veracruz, in October 2015, where we viewed the living areas for adolescent boys between the ages of 12 and 17 and for women (which also holds girls and boys who are under the age of 12, including those who are unaccompanied and separated), spoke with an additional 15 boys in the adolescents’ section, met with the National Institute of Migration (Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) commissioner responsible for the detention center and with DIF protection officials who work in the detention center. The 15 boys we spoke to in the Acayucan immigration detention center are not included in the total number of interviews given above because these conversations were not individual, detailed interviews, although they were out of the earshot of guards and provided useful information about conditions of detention, individual children’s reasons for leaving their home countries, and the status of their applications for refugee recognition for those who had made such applications.

Earlier, in February 2015, we had made a written request to the INM for access to Siglo XXI, the immigration detention center in Tapachula.[1] We applied for access under provisions of Mexico’s immigration regulations that allow such access for members of nongovernmental organizations and other individuals.[2] We did not receive a reply in writing. When we called the INM in March 2015, the director of the INM’s Press and Outreach Office told us orally that our request for access had been denied on grounds of national security and privacy and because the INM considered that only consular officials, the National Human Rights Commission (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos, CNDH), and the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had the authority to make such visits.[3] We also spoke in person with the director of Siglo XXI to request permission to visit the detention areas of the facility, but our request was again denied.[4]

Two male researchers conducted interviews in Honduras, southern Mexico, and the Federal District. One conducted interviews in Spanish; the other used male interpreters. Two Spanish-speaking researchers, one male and one female, conducted interviews in northern Mexico. We explained to all interviewees the nature and purpose of our research, that the interviews were voluntary and confidential, and that they would receive no personal service or benefit for speaking to us, and we obtained verbal consent from each interviewee.

All names of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees used in this report are pseudonyms. In some cases we have withheld other details, such as the location of the interview or information that would enable the identification of those who spoke to us. We have also withheld the names and other identifying information of some government officials who spoke to us off the record.

We also interviewed more than 35 Mexican government officials at various levels, including officials with the INM’s General Directorate of Regulation (Dirección General de Regulación y Archivo Migratorio); the Undersecretariat for Population, Migration, and Religious Affairs (Subsecretaría de Población, Migración y Asuntos Religiosos) of the Ministry of the Interior (Secretaría de Gobernación, SEGOB); the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, COMAR); DIF national, state, and local officials; and the National Commission on Human Rights. We also met with officials with the Directorate of Childhood, Adolescence, and Family (Dirección de Niñez, Adolescencia y Family, DINAF) in Honduras; United States embassy officials in Mexico City and Tegucigalpa; Honduran and Salvadoran consular officers in Mexico, and officials with UNHCR’s offices in Mexico and its regional office in Panama.

In addition to meeting with us, COMAR and DIF officials provided detailed responses to our requests for additional information after our face-to-face meetings. We attempted but failed to meet with officials at the INM’s General Directorate for Control and Verification (Dirección General de Control y Verificación), which carries out immigration enforcement activities, including the apprehension and detention of migrants. General Directorate for Control and Verification officials did not reply to requests in writing for meetings made in February and March 2015, and declined email requests in November 2015, citing scheduling conflicts.[5] We made an additional written request for a meeting on January 12, 2016, to which General Directorate for Control and Verification officials replied on February 5 offering us a meeting on February 9.[6] Our researcher was unavailable on that date but offered to meet with the General Directorate for Control and Verification on any date between February 11 and 19, 2016.[7] General Directorate for Control and Verification officials agreed to reschedule the meeting[8] but did not do so during the period we had offered and had not done so at time of writing. At time of writing, General Directorate for Control and Verification officials also had not responded to our written requests for information or comment on summaries of preliminary findings we sent them in August 2015 and January 2016.[9] In total, between February 2015 and January 2016, we made ten attempts in writing and by phone to meet with INM officials, to request access to detention centers, and to seek information and comment on our findings.

In addition, we interviewed over 30 staff members with nongovernmental organizations working with refugees and migrants in Mexico and returnees in Honduras. We also reviewed case files, including administrative decisions taken by COMAR and the review of those decisions by federal courts, as well as data collected by COMAR and the INM and evaluations and reports prepared by nongovernmental organizations.

Mexico adopted its Immigration Law and its refugee law (first called the Law on Refugees and Complementary Protection and, since 2014, the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection, and Political Asylum) in 2011. Amendments to each of these laws took effect on November 1, 2014.[10] These amendments did not materially change the provisions cited in this report, meaning that the provisions of these two laws cited in this report were in force and should have been applied by immigration and other authorities in the case of every migrant child and adult referred to in this report. In addition to these two laws, Mexico’s General Law on the Rights of Girls, Boys, and Adolescents, which took effect on December 3, 2014, and its regulations, adopted in December 2015,[11] include provisions applicable to migrant children. This report cites the General Law on the Rights of Girls, Boys, and Adolescents and its regulations to reflect the legal framework in effect at time of writing this report, but citations to this law and its regulations should be taken to apply only after their effective dates.

In line with international standards, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 18.[12] This use differs from Mexican law, which uses the term “child” to mean a person under the age of 12 and refers to those between the ages of 12 and 17 as “adolescents.”[13] As the Committee on the Rights of the Child and other international authorities do, we use the term “unaccompanied children” in this report to refer to children “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[14] “Separated children” are those who are “separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary care-giver, but not necessarily from other relatives,”[15] meaning that they may be accompanied by other adult family members. This use differs slightly from Mexican law, which uses the term “unaccompanied child” to refer to any child who is not accompanied by a blood relative or a legal representative.[16]

This report uses “refugee” to mean a person who meets either (1) the criteria in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol or (2) the definition set out in the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, a refugee is a person with a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” who is outside of the country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return.[17] The Cartagena Declaration definition, reflected in Mexican refugee law, includes as refugees people who “have fled their country because their lives, safety, or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.”[18]

People are refugees as soon as they fulfill the criteria in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol or meet the definition contained in the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees. UNHCR explains:

A person is a refugee within the meaning of the 1951 Convention as soon as he fulfils the criteria contained in the definition. This would necessarily occur prior to the time at which his refugee status is formally determined. Recognition of his refugee status does not therefore make him a refugee but declares him to be one. He does not become a refugee because of recognition, but is recognized because he is a refugee.[19]

I. Central American Migrant Children in Mexico

On their own and with their families, migrant children travel from Central America to Mexico in large numbers. In October 2015, the Mexican government estimated that at least 27,000 unaccompanied and separated children had entered Mexico in the first 10 months of the year.[20] That number is likely to be a significant underestimate—United States authorities apprehended 28,000 unaccompanied and separated children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras on its border with Mexico in the 12 months from October 2014 to September 2015.[21] Counting those children who come with their families, the total is much higher.

As many as half the total number of migrant children from these three countries are fleeing threats to their lives and safety, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has estimated.[22] They join others who travel for a combination of reasons, including the desire to seek better economic opportunities and to join family members living in Mexico or the United States.

Children who face specific threats to their lives and safety, including those who are threatened by gangs or who face domestic violence, and who cannot rely on protection from their own governments are refugees; under Mexico’s refugee law they should receive international protection.[23] The same is true of those who flee situations of insecurity or generalized violence that puts their lives, security, or freedom in danger.[24] In addition, authoritative guidance on international and regional human rights treaties provides that the return of children to their home countries when return is not in the child’s best interests would breach the principle of nonrefoulement. This may be the case, for instance, when the child lacks a caregiver in the home country and a relative in Mexico is willing and able to care for the child.[25]

Under Mexican law, migrants who are victims of serious crimes in Mexico are eligible for humanitarian visas, a status that allows them to remain in the country for one year,[26] and some of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were victims of such crimes, including extortion, abduction for ransom, sexual and other forms of violence, trafficking, labor exploitation, and other abuses at the hands of criminals, local gangs, and organized criminal operations.

The Number of Migrant Children in Mexico

Accurate estimates of the population of migrant children in Mexico at any given time are difficult to make, but at least 20,000 unaccompanied children have entered the country each year since 2008.[27] Most are boys between the ages of 12 and 17, although a significant number of adolescent girls, perhaps one-quarter of all child migrants, also travel to Mexico.[28] Younger children also make the journey, generally with their families but sometimes on their own.

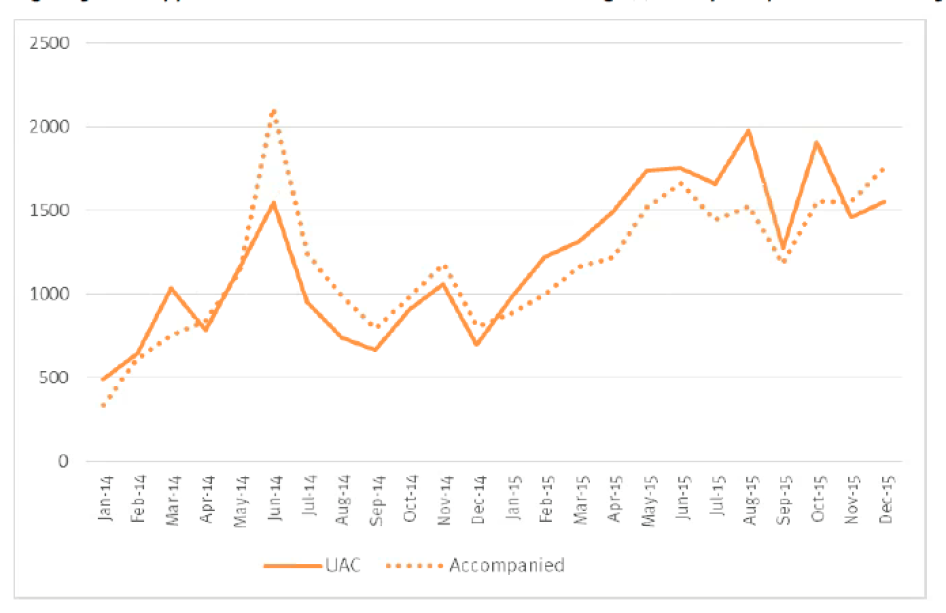

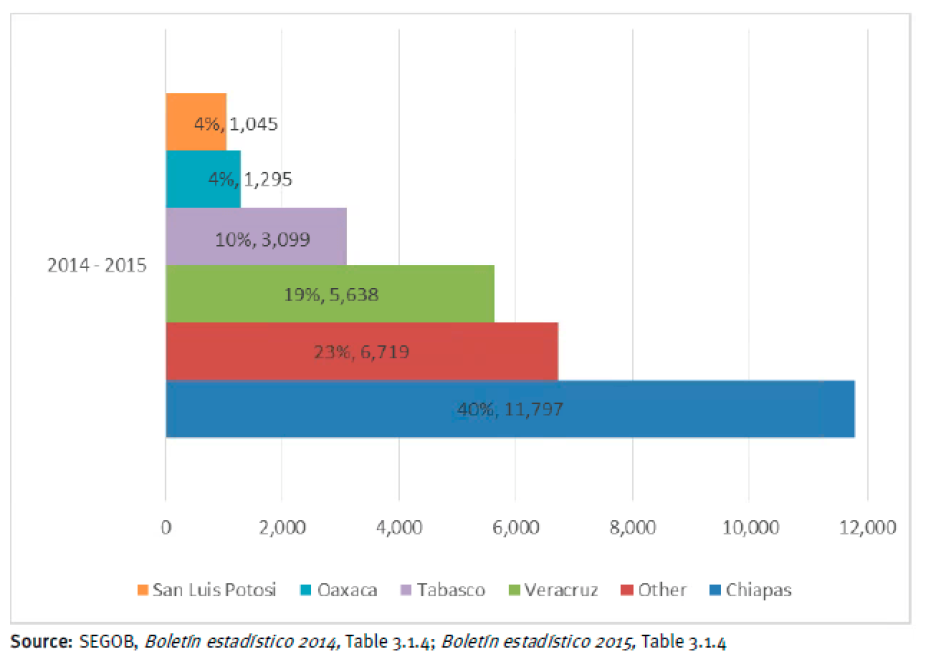

Mexico’s National Institute of Migration (INM), the agency responsible for enforcing the country’s immigration laws, made nearly 36,000 apprehensions of children under the age of 18 between January and the end of December 2015. Of that total, more than 18,000, or just over half, were unaccompanied. Just under two-thirds of the total was between the ages of 12 and 17, and boys outnumbered girls by two to one.[29] The INM made 23,000 apprehensions of children in all of 2014 and 9,600 apprehensions of children in 2013. This means that apprehensions of children in 2015 increased by 52 percent over the whole of 2014 and by nearly 275 percent over the total for 2013.[30]

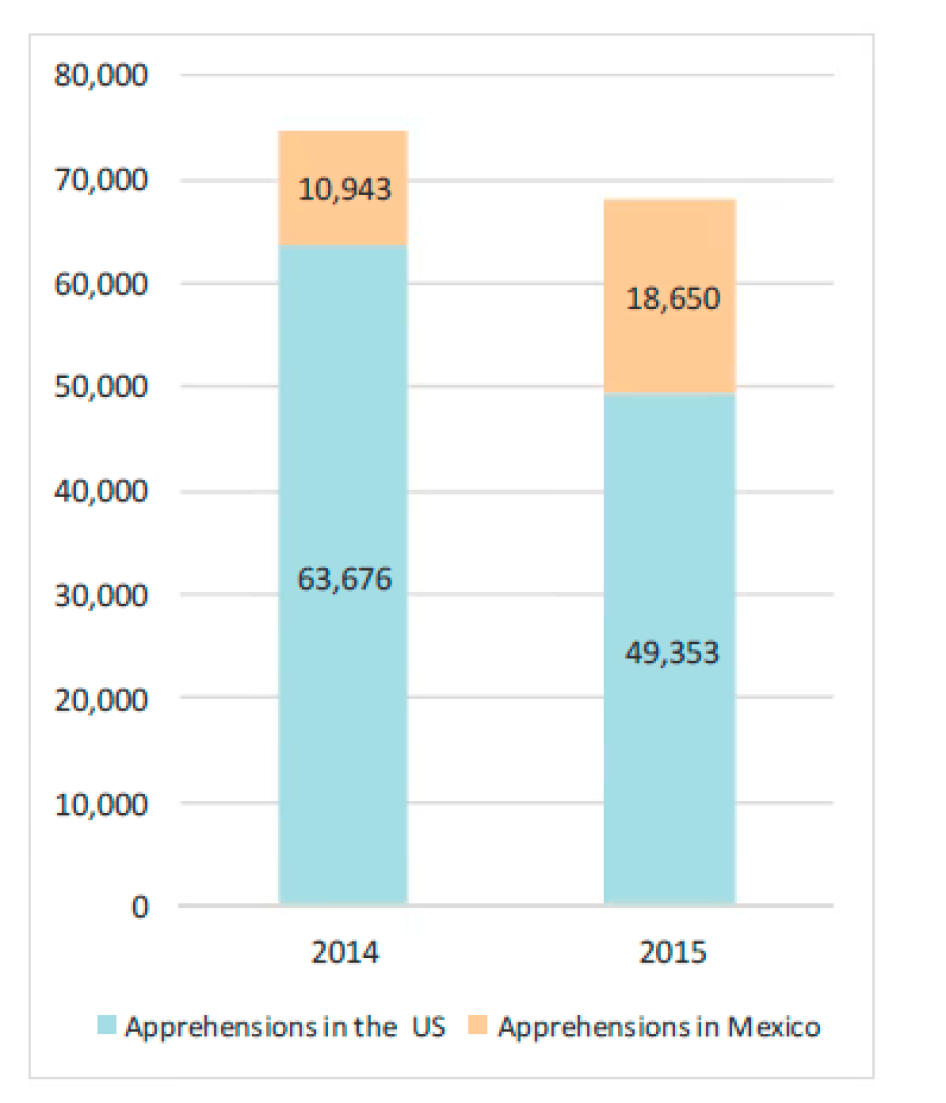

In combination, Mexican and US authorities apprehended almost 75,000 children from Central America’s Northern Triangle in calendar year 2014 and 68,000 in calendar year 2015, figures that include accompanied as well as unaccompanied children.[31]

These numbers do not include children who never came into contact with the INM or with US authorities—those who are living undetected in Mexico or who attempted and possibly succeeded in crossing into the United States. They also do not include children who apply for recognition of refugee status at one of the three offices of the Mexican Commission for Refugees (COMAR) without ever being apprehended by immigration authorities, because children and adults who apply directly with COMAR are not taken into INM custody.

Why They Flee

Gang violence has plagued El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras for more than a decade.[32] The governments of these three countries have proven unable or unwilling to control gangs: as UNHCR observed in an October 2015 report, “[i]n large parts of the territory [of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras], the violence has surpassed governments’ abilities to protect victims and provide redress.”[33]

The murder rates in El Salvador and Guatemala were in the range of 40 per 100,000 in 2012, making them the fourth- and fifth-highest in the world that year. Honduras, with a rate of 90 per 100,000, has had the world’s highest homicide rate for several years running,[34] although recent reports suggest that El Salvador may now hold that dubious distinction.[35]

Children are specifically targeted by gangs in these three countries. In Honduras, for example, over 400 children under age 18 were killed in the first half of 2014, most thought to be the victims of gang violence.[36] It is not uncommon to hear reports of 13-year-olds, or even younger children, being shot in the head, having their throats slit, or being tortured and left to die.[37]

It is unsurprising, then, that children have been leaving El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, on their own and with family members, for years. Nearly half of the children who spoke to Human Rights Watch told us that they chose to leave their homes to escape violence or because they were targeted by local gangs. When children fled together with their families, they or their parents often spoke of specific concerns for the children’s lives or safety—including gang recruitment; sexual violence, particularly against girls; and domestic violence that had an effect on children in the household. Three of the children who traveled to Mexico alone told us that they were hoping to reunite with mothers, fathers, or siblings because their grandparents or other elderly caregivers were no longer able to care for them.

Elizabeth Kennedy, a Fulbright scholar who examined Salvadoran children’s stated reasons for migrating, found that “crime, gang threats, or violence appear to be the strongest determinants for children’s decision to emigrate. When asked why they left their home, 59 percent of Salvadoran boys and 61 percent of Salvadoran girls list one of those factors as a reason for their emigration.”[38]

A 2014 UNHCR study found that some 48 percent of the unaccompanied Central American children interviewed in Mexico in 2013 cited some form of violence (including beatings, threats or other acts of intimidation, and insecurity) as among the reasons they left their countries and concluded that these children were potentially in need of international protection.[39] Of the children interviewed for the UNHCR study, Hondurans were most likely to be fleeing violence and insecurity.[40]

Similarly, a study coordinated by the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies of the University of California Hastings College of the Law and the Migration and Asylum Program of the National University of Lanús, in Argentina, included interviews with 200 children between the ages of 10 and 17 who were deported from Mexico to Honduras. Sixty-five percent of the Honduran children interviewed for the study said that the desire to escape violence was the main reason they decided to migrate. “The most common forms of violence they mentioned included death threats from criminal groups, the continuous fighting between rival gangs, common crime, and domestic violence,” the study found.[41]

These findings match those of another 2014 UNHCR study, which examined the international protection needs of unaccompanied or separated children who had arrived in the United States from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, as well as Mexico, and concluded that 58 percent had “suffered or faced harms that indicated a potential or actual need for protection.”[42] Of the children from Honduras, 57 percent raised potential international protection concerns. Children from El Salvador were even more likely to have international protection needs, with 72 percent of those interviewed raising such concerns.[43]

Gang Recruitment

One of every five children we interviewed told us that pressures to join gangs were the primary motive for them to migrate. For example, Byron O., age 15, said he left his home in the Cortés department of Honduras together with his parents and other family members because the gang in his area was trying to recruit him. After several attempts to persuade him to join, a group of gang members surrounded him while he was walking on the street near his home. “They said they were going to kill me if I didn’t join them,” he said. “The next day, we left.” He and his family spent 10 days in Tecún Umán, in Guatemala just across the border with Mexico, before crossing and traveling to Tapachula. They had applied for asylum but had not yet been interviewed at the time we spoke.[44]

Gabriel R., another 15-year-old from the Honduran department of Cortés, had a similar account. “I was in school, in the ninth grade. One day the gang came up to me near the school where I was studying. They told me that I needed to join the gang. They gave me three days. If I didn’t join them, they’d kill me. . . . It was a group of six or eight guys. Some were 14, 18, 21 years old. The oldest was about 26.” He left Honduras on his own before the three days were up.[45]

Other children, including 17-year-old Lionel Q. and 15-year-old Marco A., from Honduras, and 16-year-old Hugo R., 16-year-old Rudy B., 17-year-old Joseph H., and 17-year-old Charly T., from El Salvador, gave accounts that were substantially similar,[46] and which correspond with the findings of other researchers.[47] “They wanted me to join the gang,” said Lionel, who left San Pedro Sula in September 2014. “When I told them no, they started to threaten me. They said they would kill me and my family. I was living in a lot of fear. To the gangs, a life isn’t worth a sandal. I mean, it isn’t worth anything.”[48] Rudy and Charly each showed us scars on their abdomens from operations that saved their lives after they were shot by gang members after they refused to join.[49]

We heard accounts that suggested that pressure to join gangs was the norm in many communities in Honduras and El Salvador. “All of the young people are approached to join the gangs,” said Enrique J., a 17-year-old from La Ceiba, Honduras.[50]

Parents also mentioned fears that gangs would try to recruit their children as among the reasons they fled. Esther A., age 39, fled El Salvador in December 2014 after her children were targeted in a variety of ways, including efforts by the Mara 18, a regional gang, to recruit her 11-year-old son to deliver and sell drugs in his school.[51] Karla V., whose primary motivation for leaving Honduras was to escape domestic violence at the hands of her husband, told us that she was also afraid of what would become of her children if they grew up in Honduras. “There, nine-year-old children are obligated to join the gangs,” she said. “I realized that if I stayed, my son would become a gang member.”[52]

Rape and Sexual Harassment, Abuse, and Exploitation

A related motivation for some is the desire to escape ongoing or threatened sexual harassment, rape, and other sexual abuse by gangs.

Esther A., the 39-year-old woman from El Salvador, told us that a group of gang members tried to rape her 15-year-old daughter. Her 11-year-old son drove off his sister’s attackers, but police were indifferent to the family’s attempt to report the attempted rape and the beating her son suffered. She told Human Rights Watch:

He saw her purse lying near the cemetery and then he saw five guys trying to rape her. He got a stick and started swinging it at the rapists. The rapists, the five, they grabbed my son. When he came back, I said, “What happened to you?” I saw he was all beaten up. His right leg was punctured. I took him to the police. The police just told him to keep out of trouble. They told him, “You should have let them rape your sister.”[53]

Heidy D. told us that she left Honduras with her family after gang members started expressing interest in her older daughter. “My daughter—at 13 years old, she’ll be considered a woman. The gangs are recruiting girls of that age to be their women. I said, ‘Please, she’s 12 years old,’” she recounted. “The gang comes to the house. If they see something they like, you have to give it to them.” She had told her daughters to stay inside the house as much as possible to avoid drawing the attention of gang members, but her 12-year-old daughter had grown unwilling to stay indoors for most of the day. “When my daughter left the house, I thought they would take her too. I said, ‘Don’t play like that.’ . . . Things are really hot in the neighborhood where we live.”[54]

Alejandra M., a 39-year-old Salvadoran woman, told us that she stopped sending her 17-year-old daughter to school because she feared that her daughter would be sexually assaulted. “Five guys wanted to abuse her. They were from the gang. . . . They were going to rape her,” she reported. As discussed below, she left El Salvador with her family when gang members threatened her family after she fell behind on extortion payments.[55]

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Hondurans deported from the United States in late 2014, we heard similar fears. Cecilia N., a 14-year-old who had left Honduras with her mother, said of the gangs in her neighborhood, “I’m terrified because they have taken girls from my school and raped them.”[56]

Crimes of violence against women and girls are high in all three countries of Central America’s Northern Triangle. In Honduras, for example, violent deaths of women in Honduras increased by 263 percent between 2005 and 2013. Impunity is the rule for femicide and crimes of sexual violence, the United Nations special rapporteur on violence against women found during a visit to the country in July 2014.[57] Similarly, the special rapporteur found during her 2011 visit to El Salvador that murders of women had nearly doubled between 2004 and 2009.[58] El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala have the first-, second-, and fourth-highest female homicide rates in the world, respectively, according to the 2015 Global Burden of Armed Violence report.[59]

Abduction for Ransom

Several of the children Human Rights Watch spoke with said that they fled, alone or with their families, after they or their family members were held for ransom or threatened with kidnapping.

Karina J., 17, was one of two children, among the 61 we interviewed, who was kidnapped. She was abducted in San Salvador by a local gang in 2013 and held for ransom. “They beat me all over and punched me in the face. The guy who hit me said, ‘This is so your family knows I’m not kidding,’” she reported. She was held for three weeks while the gang demanded $10,000 for her return. After she was rescued by the police, her family fled to Guatemala, but they had to return to El Salvador six months later when their money ran out. “We spent another year in San Salvador,” Karina said. “We didn’t leave the house unless we had to. We were so afraid. I was terrified.”[60]

Johanna H., 17, had a similar account. She left Guatemala in April 2014 with her extended family after she was kidnapped by a local gang and released only after her family paid ransom for her safe return. In addition, one of her brothers had been kidnapped five years before, when he was 16, and another had been killed. After her kidnapping, “we couldn’t go to school,” she said, referring to herself and her two sisters. “There were too many risks. We couldn’t stay in Guatemala anymore.”[61]

In other cases, the children of abducted parents were threatened if the families did not pay the ransom. Elena L. was one of five people interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had an immediate family member abducted. Her 33-year-old daughter was held for two weeks and repeatedly raped by members of the Mara 18 in June 2014. “They told me I would have to pay 50,000 lempiras [$2,235] or they would kill the children too,” Elena L. reported, referring to her grandchildren, ages 15, 13, and 11. The family, six in all, left Honduras after her daughter was rescued by police.[62]

Two parents told us that they relocated their families in response to direct threats that their children would be abducted. For instance, Patricia A. told us that and her family left Honduras after a local gang threatened to kidnap her nine-year-old son.[63] In addition, when Human Rights Watch interviewed children who had been deported from the United States to Honduras for a 2014 report, one parent told us:

[T]hey [the local gang] tried to kidnap my son in June 2014. I usually come early to school to pick up my son at lunchtime. They got there maybe 10 or 20 minutes before the kids come out. I recognized them. They had already told me that something was going to happen to my son and to my wife. I didn’t hesitate. I jumped the school fence with my son. I pushed him over and then I jumped. Later in the day, the teachers told me that [the gang members] were looking for a kid of my son’s age. I didn’t send him back to school. . . . We had some savings from three or four years so I sent my son and my wife to the United States. Once I knew they were safe, I fled too.[64]

Extortion

Almost ten percent of the children with whom we spoke with fled their homes, with their families or sometimes on their own, after extortion payments became too high or their families fell behind on payments, prompting threats or reprisals from gangs.

Carlos G.’s situation is an example. He told Human Rights Watch that he left San Salvador alone in 2011, when he was 17. “There were many problems there—crime, gang violence,” he said. His father, who owned a small store, paid local gang members a “rent” of $100 per week. “He did this so that the gang wouldn’t do anything to my two brothers and me,” Carlos G. said. “He had to pay or they would take us from our school.” His father was able to keep up these payments until April 2009, when he could no longer afford it. As soon as his father missed a payment, the family started finding letters on their doorstep demanding payment in full. “This happened three times—we didn’t pay them three weeks in a row, so we owed $300,” he told Human Rights Watch.

Early one morning, Carlos’s father was shot and killed on the street as he left the house. “I saw it happen,” he said. “Some men came up to him and shot him eight times. Then they ran away.” After his father was killed, he started to receive threats. “Two notices came for me. They were going to kill me. My family had to hand me over to the gang or I would be killed. I had to get out of there and find a place where I could stay. I was very scared. I left the house and went to stay with my grandmother, but the same gang was there too. They’re everywhere in El Salvador,” he said. He was able to stay with his grandmother until September 2011, when he started to get threats again. He left El Salvador shortly after the threats resumed.[65]

We heard other accounts that were similar to Carlos’s. “Every week we had to pay 100 or 200 lempiras [between $4.50 and $9] to the gang,” 17-year-old Samy O. from Honduras told us. “They walk around with guns, so we had to pay them. This was going on since January. Every week in January, February, March, April, May, up until when we left.”[66] Samy O.’s family decided to leave Honduras in mid-May 2015 because they did not think they could continue to make the payments.

In other cases, children told us that gangs targeted them after they or their employers refused to make work-related extortion payments. Joel E., a 16-year-old from La Ceiba, Honduras, collected bus fares from passengers. “The gang wanted a war tax [impuesto de guerra] from the driver and each of the assistants. The war tax was for the bus route. To cross the gang’s territory, you have to pay the war tax. They said we had to give them money or they would kill us. They gave us three days to pay.” Realizing that he could not afford the amount they demanded, he fled La Ceiba before the three days were up.[67]

Some families in this situation told us that they took the decision to relocate as a group to Mexico when their children were threatened.

For instance, Alejandra M., age 39, fled El Salvador in December 2014 after members of the Mara 18 threatened to harm her children if she did not pay them. “They showed up with revolvers and AKs. ‘Where is the rent?’ they demanded. ‘I don’t have any money,’ I told them. ‘Go find the money.’ They gave me 72 hours to pay them $7,500. If I didn’t, they would kill two of my children.” She also feared that her daughter would be raped.

Alejandra put her house up for sale and accepted the first offer she received. “At 8 a.m. the next day I sold my house for $6,000. At 4 p.m. I handed $5,500 to the gang members. I couldn’t give them the full $7,500.”

When she realized that the gang expected the full amount, she traveled with her 17-year-old daughter and 11-year-old son to Mexico, where she was apprehended and placed in detention. She said she had little hope for her pending asylum application, because other migrants have told her that approvals are rare. “I told the people here that I had been threatened, but they didn’t take me seriously. I’ve been here for three months,” she said. “I still owe $1,500 to the gang. I don’t have a house anymore. I don’t have anywhere to live. The Mara 18 show no mercy.”[68]

Gang Violence and Barriers to Education

Several children and parents told us that children were at risk of recruitment and other abuses by gangs as they walked to and from school. “To get to school, we had to pass by the place where the gang members were,” said Carlos G., who left San Salvador in 2011, when he was 17.[69]

As a result, some children stopped attending classes in order to avoid the gangs as they went to and from school. “The kids couldn’t go to school because there’s a lot of crime,” said Bianca H.[70] “The gangs are waiting on the corner outside the school,” Patricia A., the mother of a nine-year-old boy, told us.[71] Maikel O., 19, said that he left Honduras in May 2015 because he hoped to finish his education in Mexico. “I didn’t go to school because there are many problems . . . many gangs” around his school, he said.[72] Esther A., the woman whose 11-year-old son was beaten by gang members when he prevented them from raping his sister, withdrew her daughter from school after the attack.[73] And as noted above, Alejandra M. kept her 17-year-old daughter out of school after she began to fear that her daughter would be sexually assaulted by gang members.[74]

Generalized Violence

Nearly half of the children and adults we interviewed told us that the general insecurity in their home countries was a major factor in their decision to depart. “Life is ugly where I live,” said 11-year-old Omar C., from Ocotepeque, Honduras, near the border with El Salvador and Guatemala; he told us that his grandparents decided that he would be safer if they sent him to join his mother in the United States.[75] “The boys in the gangs are walking around in the colonias [neighborhoods] as if they were the police, walking around armed,” 34-year-old Heidy D. said of the community where she lived with her children in La Ceiba, Honduras.[76] Marjorie B., 21, told us that she, her 17-year-old brother, and their 15-year-old sister left their home in El Paraíso, Honduras, because of the high level of crime where they lived. “It’s not safe there,” she told Human Rights Watch.[77] Similarly, Bianca H., age 38, explained why she left Honduras with her three teenage children: “We couldn’t live here. The violence, the crime, it’s constant.”[78]

Such fears are reasonable. Four children we interviewed had been victims of violent crime at the hands of gang members, and many others personally knew victims of violence. “There’s a lot of crime in my neighborhood, a lot of gang activity. They robbed my mother’s house and raped one of my sisters” in 2007, reported Enrique J., 17. His sister left Honduras shortly afterward and joined their father in the United States, where she received asylum; other relatives have settled in Mexico. Even then, he stayed in Honduras until he was beaten and robbed by gang members while working as a mechanic. “They assaulted me and robbed me,” he said. And when he spoke to his mother the day after immigration authorities apprehended him in northern Mexico, “she gave me the bad news that one of my cousins was just killed by the same gang,” he told Human Rights Watch.[79]

Enrique J. and his girlfriend have a son together. “Originally I didn’t want to leave Honduras, because I didn’t want my child to give up his dad the way I had to. I didn’t want him to grow up not knowing his father. But the way things are now, the situation is really ugly,” he said.[80]

After its December 2014 country visit to Honduras, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Inter-American Commission, IACHR) observed: “The widespread context of violence and citizen insecurity makes Honduran children and adolescents especially vulnerable. The IACHR received information from civil society indicating that 454 children and adolescents had died between January and June of this year [2014] because of the violence in the country.”[81]

In all, 1,031 children and youth up to the age of 23 were killed in Honduras in 2014, the Observatorio de Derechos de los Niños, Niñas y Jóvenes en Honduras and Casa Alianza found, approximately the same as the previous year. Five departments—Cortés, Francisco Morazán, Atlántida, Yoro, and Santa Bárbara—accounted for 90 percent of these violent deaths in 2014, with Cortés alone accounting for nearly half the total.[82] (That is not to say that children (or adults) can seek safety elsewhere in the country—in fact, as discussed in subsequent sections of this report, those who relocate within the country are frequently thought to belong to rival gangs, meaning that they face no less serious risks.[83]) Most of these deaths were caused by firearms, knives and other bladed weapons, or blunt instruments. Asphyxiation was the cause of death in 8 percent of these cases, with many bodies showing signs of torture before death. The two groups observed that many of the asphyxiated victims were “inside sacks, plastic bags, tied up with rope, or wrapped up in sheets; the victims were strangled to death.”[84]

Domestic Violence

We heard several accounts from children who fled abusive situations at home and could not find protection within their own country, meaning that they had potential grounds for recognition as refugees in Mexico. For instance, Wendy V., a 16-year-old girl from Copán, Honduras, told us that she left an abusive relationship with the father of her child. She had reported the abuse to the police, who sent the man a notice to appear in court but did nothing when he failed to appear, and she did not pursue the case because the man threatened to harm their child if she continued to report the abuse against her.[85] When UNHCR interviewed Central American children in the United States, 21 percent of Salvadorans, 23 percent of Guatemalans, and 24 percent of Hondurans reported that domestic abuse was a reason for fleeing.[86]

We also heard from one teenager who left his home after experiencing violence at the hands of relatives because of his sexual orientation. “I’m gay,” 17-year-old Arturo O., from Guatemala, told Human Rights Watch. “My father couldn’t accept me. He couldn’t accept that I’m attracted to people of the same sex. I said, ‘I am who I am. I can’t change.’ Things with my father were very difficult. My brothers also harassed me. After a while, I couldn’t continue to live at home. I needed to get out, to get away from the problems I was having with my father.”[87]

An official of a local government agency dedicated to family development told us of similar cases. “I’ve seen young people who leave when they suffer abuses at home. A 12- or 13-year-old says, ‘I’m gay,’ comes out to the family. They can suffer abuses at any moment. An uncle shows up and says, ‘Come with me, you’re confused,’ and the situation becomes violent. I’ve seen boys of ages 12, 13, 14 in this situation,” an official with a local entity of Mexico’s child protection system, the National System for Integral Family Development (DIF) told Human Rights Watch, speaking of Central American children with whom she had come into contact.[88]

A couple of the women who said that they left to escape domestic violence told us that they took the decision to leave when they realized that their children were affected, either because the children had started to become aware of the abuse or because they were subjected to physical violence themselves.

For example, Karla V., a 29-year-old Honduran woman, told us that after she had been beaten several times by her husband, “I made a complaint to the police. They detained him for 24 hours and then let him go. They told me that the next time they would lock him up for 48 hours. What does that do for me? He always hit me. If I made another complaint, he would go back to beating me. He used cables, rocks, whatever. He hit me whenever he was angry about something. If I responded, he would hit me again.” She left for Mexico in March 2015 with her children, hoping to live with her aunt and her cousin in Mexico City. “The father of my child threatened to kill me if I return to Honduras. That’s why I’m afraid to return. There, the death of a human being is like the death of a dog: it’s never punished. I knew when I left that I ran a big risk. I knew I risked danger. If I go back, my children will be left orphans.”[89]

Women and girls are often unable to secure effective state protection against domestic violence in the three countries of Central America’s Northern Triangle. In Honduras, for example, the country’s special prosecutor for women described the police as “ineffective” in a 2012 interview with Proceso, a national newspaper, noting that of “the 66,000 complaints [of violence against women] filed every year with the National Directorate of Criminal Investigations [Dirección Nacional de Investigación Criminal, DNIC], only a few are investigated by the police.”[90] At the conclusion of a July 2014 country visit to Honduras, the UN special rapporteur on violence against women noted:

[A] lack of effective implementation of legislation, obstacles such as gender discrimination in the justice system, inconsistencies in the interpretation and implementation of legislation, and the lack of access to services that promote safety and also address prevention of future acts of violence. Moreover, corruption, the lack of political will, and the failure of authorities to exercise due diligence in investigating, prosecuting and punishing perpetrators of violence against women contributes to an environment of impunity, resulting in little or no confidence in the justice system.[91]

Women and girls in El Salvador and Guatemala confront similar obstacles. A 2011 investigation by the Inter-American Commission on states’ responses to sexual violence found that in all three countries, as well as in Nicaragua:

a woman victim of violence who, after wrestling with her own circumstances, decides to report the violence she has experienced, then has to contend with a justice system in which stereotypes and prejudices are pervasive; a justice system that blames her, discriminates against her, and ends up rendering a judgment slanted against her. She also has to deal with an understaffed and underfunded system for the administration of justice, tied up in procedural formalities; a system that forces her into mediation to settle her dispute, is incapable of securing the necessary medical evidence, requires witnesses, and fails to coordinate with the other institutions involved in the investigation, among other problems.[92]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons, particularly children, often face similar obstacles in reporting and securing effective state protection against acts of violence, including domestic violence.[93]

Elderly Caregivers

In many cases, children are cared for by grandparents or other relatives after their parents leave the country. Three children in this situation told us that their elderly caregivers had died or had become increasingly concerned about their ability to look after the children as they aged. Particularly given the general context of insecurity, elderly caregivers and children themselves may decide that the children will be better off if they can join one or both parents or other relatives in Mexico or the United States.

“I lived with my grandmother, but then my grandmother died,” Daniel L., a 15-year-old boy from El Salvador, told Human Rights Watch. “My grandmother never wanted me to have any vices. She always made sure I never smoked. She told me, ‘If I die, you go to Mexico, where you can have a better life.’ I have my father, but he is an alcoholic.”

His grandmother died in October 2014. The next day, Daniel learned that she had arranged for him to be taken to Mexico as soon as she passed away. “My grandmother had paid for everything. I didn’t know this, but well beforehand she had paid all the expenses for my travel.”

The man with whom his grandmother had made the arrangements told him that he would be going to work in Cancún. “I don’t know what kind of work it was,” Daniel told us. When they reached Comitán, he recounted, “The man went to go eat something in a restaurant. He drove off, and he never returned for me. . . . I felt very anxious because I didn’t know anybody there. I didn’t know what to do. Somebody helped me find the municipal police. They treated me well. They took me to Immigration, and I told my story to somebody from the Salvadoran consulate. He told me to seek help from COMAR.”

Daniel applied for asylum and was awaiting a decision when we interviewed him in May 2015. “I don’t want to return to El Salvador,” he said. “I would have to stay in a shelter, and there are all the gangs.”[94]

Similarly, Omar C., age 11, had been living with his grandparents in Ocotepeque, Honduras, before he left at the end of May 2015, accompanied only by a smuggler, intending to go to the United States. “Life is bad where I lived,” he said, explaining that his grandparents feared they could not protect him from gang violence. His mother has been living in Virginia since he was three years old, and he hoped to join her there.[95]

Catarina H., a 13-year-old girl from Olancho, Honduras, gave a similar account. “I was living with my grandmother in Honduras, but she is sick,” she said. “If my grandmother dies, what am I going to do?” She decided to make her way to the United States, where her mother and father both live; her father, whom she has not seen since she was a baby, is a US citizen.[96]

Caseworkers in Mexico described similar situations they had seen with Central American children. “In September 2014, I saw two brothers who had been living with their great-grandmother until she died. The grandmother is in the United States. They don’t have anybody else to care for them,” one local DIF official told us.[97]

Abuses During the Journey

Central Americans’ journey to and through Mexico is arduous and risky. In every country they pass through, migrants are vulnerable to being preyed on by gangs, criminals, and the people they have paid to guide them to their destination. “It’s dangerous because you can be assaulted. The gangs kidnap people. We spent days walking, hiding, going around the immigration checkpoints,” said Kevin B., a 15-year-old from El Salvador, of the journey he and his 14-year-old brother made through Mexico with the aid of a coyote, or smuggler, before they were apprehended near Tijuana.[98]

When migrants are the victims of serious crime in Mexico, they are eligible for “humanitarian visas,” which allow them to remain in Mexico for one year at a time, with the possibility of renewal for further one-year intervals.[99] Human Rights Watch spoke to 15 children and adults who were victims of crimes such as extortion and armed robbery, sexual violence, abductions for ransom, and other violent crime in Mexico.

Edwin L., a 16-year-old from Honduras, told Human Rights Watch that he and the group he traveled with were held for ransom near Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, in May 2015. He spent eight days captive and was released only after his family wired $2,000 to his captors. “If I didn’t pay them, they were going to kill me,” he said. He described the experience:

We arrived in Coatzacoalcos with our guide. The same guide turned us over to the [armed gang known as the] Zeta. There were 15 of us in the group. All 15 were kidnapped. . . . It was the morning after we arrived. Some men came to the place we were staying. Some had guns; others had machetes. They started threatening us. ‘If we don’t get the money, we’ll kill you.’ . . . We had to pay the money. There wasn’t any other way. They burned me with an electric cord to get me to call my family. I called, and my family arranged to send 43,000 lempiras [approximately $1,950]. They gave us a name to send the money to.[100]

After his family paid the ransom, he continued his journey north. “We didn’t report the kidnapping,” he said, explaining that he thought he would be deported if he did so. “If you report a crime to the police, they would only turn you over to Immigration. They’re not going to help you.” He was apprehended by INM agents as he tried to cross the Rio Bravo del Norte, the river known as the Rio Grande north of the border, to enter the United States. He was awaiting deportation to Honduras when we interviewed him in June 2015.[101]

Edwin’s account is by no means unusual: the Mexican National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) has found that migrants are subject to abduction for ransom in large numbers.[102]

Others described being the victims of armed robbery or extortion. For instance, armed men robbed Rodrigo L., a 30-year-old Salvadoran man, taking nearly $2,000, shortly after he crossed into Mexico at El Ceibo, near Tenosique, together with his wife, 12-year-old son, and eight-year-old daughter.[103] Seventeen-year-old Arturo O., from Guatemala, had a similar account. “I was assaulted at the border,” he said. “They took my money and my phone.”[104]

A 2013 analysis by the Jesuit Refugee Service/USA (JRS) of data collected by the Mexican Migration Southern Border Survey (Encuesta sobre Migración en la Frontera Sur de México, EMIF Sur) found that over a four-year period, almost 15 percent of migrants interviewed by EMIF Sur reported extortion in Mexico. Nearly 12 percent of migrants reported attacks or robbery in 2012, the first year that EMIF Sur included these categories on its survey.[105]

Sexual violence is another risk, for boys as well as girls. UNHCR observed in its report on children who had traveled through Mexico to reach the United States: “A troubling note is that staff members at two different ORR [the US government’s Office of Refugee Resettlement] facilities stated they are seeing an increase in male residents reporting incidents of sexual abuse, occurring particularly during their journey to the US.”[106]

Other groups, including Amnesty International, Centro Prodh, i(dh)eas, and Sin Fronteras, have also documented abuses against migrants during their journey in Mexico, including kidnappings, sexual violence, other forms of violence, and extortion.[107] In addition, the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has observed that migrants are at risk of enforced disappearance—abduction by a state agent or with the state’s acquiescence, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the abduction or the whereabouts of the abductee[108]—as they travel through Mexico.[109]

Mexico as a Country of Destination

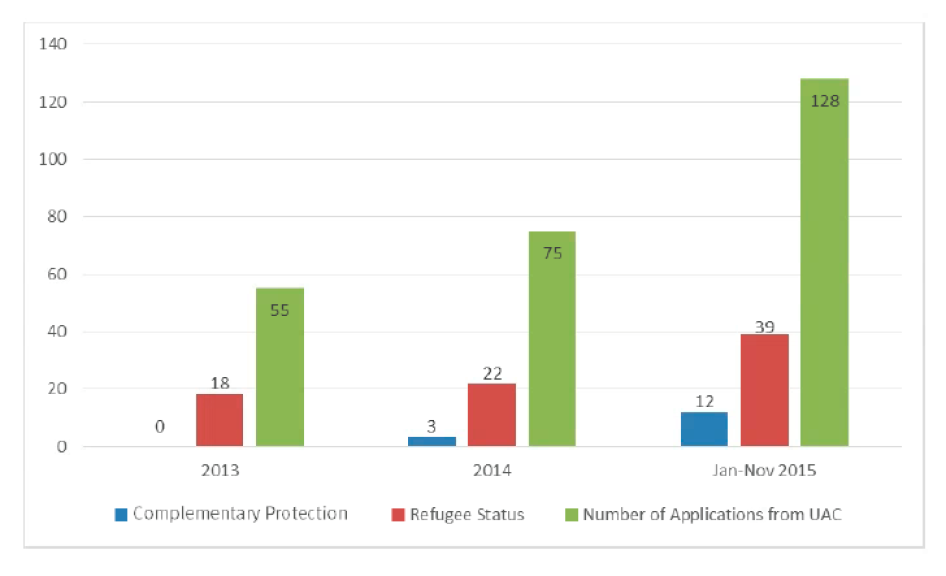

Mexico is often thought of as a transit country for migrants seeking to reach the United States. But it received Central American refugees in large numbers in the 1980s—some 150,000 from Guatemala alone between 1980 and 1984 and 120,000 or more from El Salvador during this period.[110] In recent years, nationals of these three countries of Central America’s Northern Triangle have again arrived in Mexico in substantial numbers, as measured by apprehensions, which have increased from 80,000 in 2013 to 118,000 in 2014 and 170,000 in 2015.[111] The number that submits claims for international protection is much lower but is also increasing: COMAR received just under 1,300 applications for refugee recognition in 2013, some 2,100 in 2014, and 3,044 in the first 11 months of 2015.[112]

The United States continues to be the destination of choice for many Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans, a consequence not only of its strong economy and relative proximity but also of their sense that they will receive a fair hearing and the strong family ties that many Central Americans have in the country.[113] Nevertheless, Mexico and other countries in the region—Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panamá—have seen significant increases in asylum applications. Taken as a whole, these countries report a 432 percent increase in asylum applications since 2008.[114]

An asylum seeker’s choice of destination is influenced in part by the presence of family members in that country. Six children fleeing violence in their home countries told Human Rights Watch that they hoped to live with family members already in Mexico. An additional 12 children who fled violence had relatives in the United States whom they hoped to join.

The Role of the United States

Record numbers of unaccompanied children and families from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras arrived in the United States in the first half of 2014, in what was widely referred to as a “surge.”

The US policy response to this sharp spike in Central American arrivals included a redoubling of efforts to promote immigration enforcement and deterrence measures in Mexico and the countries of the Northern Triangle. US policymakers often referred to the Central Americans who transit Mexico as “illegal migrants,” but, as earlier sections of this chapter illustrate, there is considerably more to the story than this pejorative term suggests.

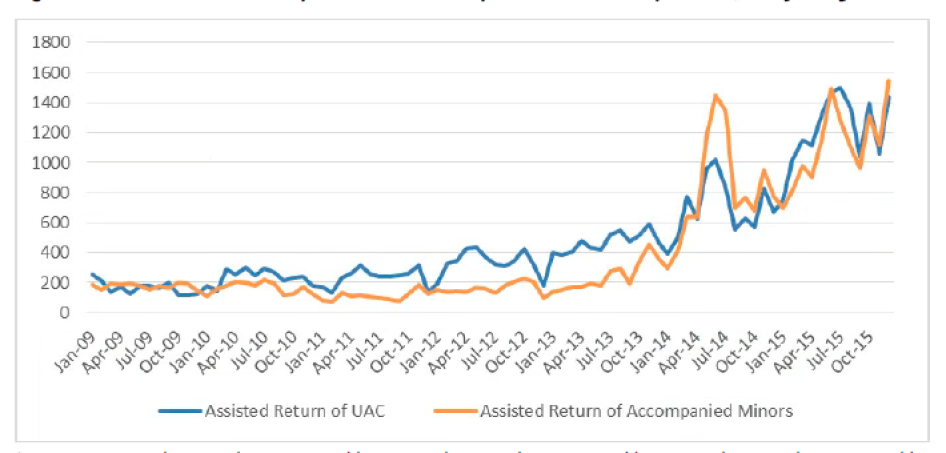

These efforts appear to have had their intended effect, at least through much of 2015. As detailed below, US apprehensions of unaccompanied children from the Northern Triangle fell by 22 percent in 2015 compared to 2014, while Mexican apprehensions increased by 70 percent during the same period. Although the US aid to Mexico included some funds for measures intended to combat the victimization of migrant children, the increased US funding was primarily to support immigration enforcement and did little, if anything, to help strengthen Mexico’s system for ensuring that children in need of refugee protection are able to access it.

Despite increased US support for immigration enforcement in Central America and Mexico, arrivals in the United States of Central American unaccompanied children began rising again at the end of 2015.

The Increase in Arrivals

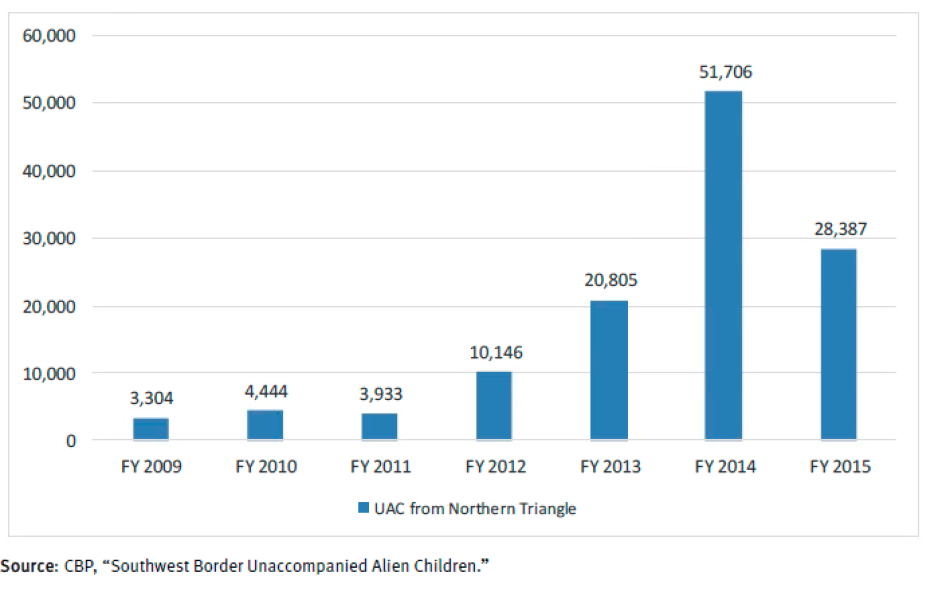

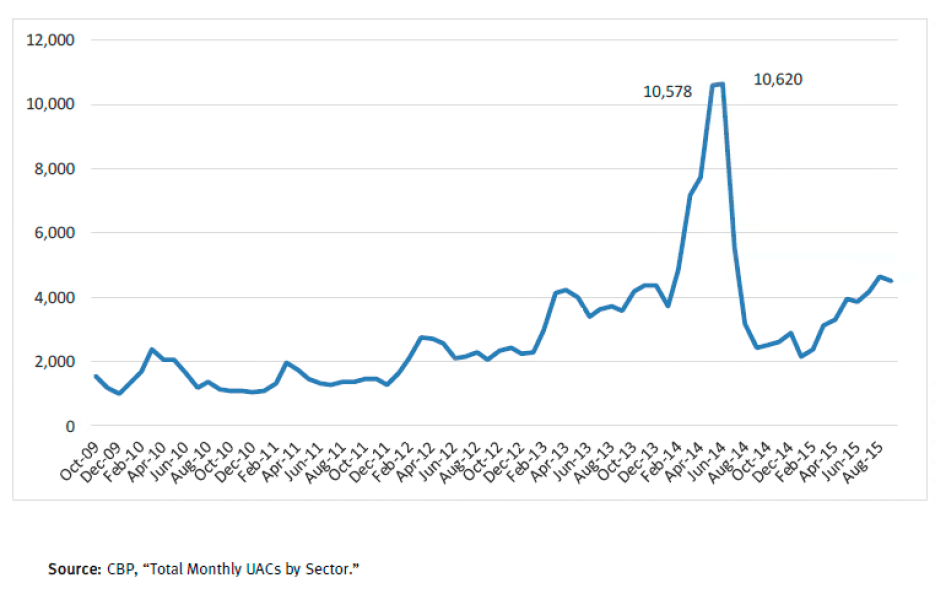

An increasing number of unaccompanied children started arriving at the southern border of the United States in 2012, with the number up sharply in 2014. US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) apprehended nearly 52,000 unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras during FY 2014, the 12-month period beginning October 1, 2013, nearly three times as many as in FY 2013. Most of these apprehensions took place from February to June 2014, peaking in the last two months of this period.[115]

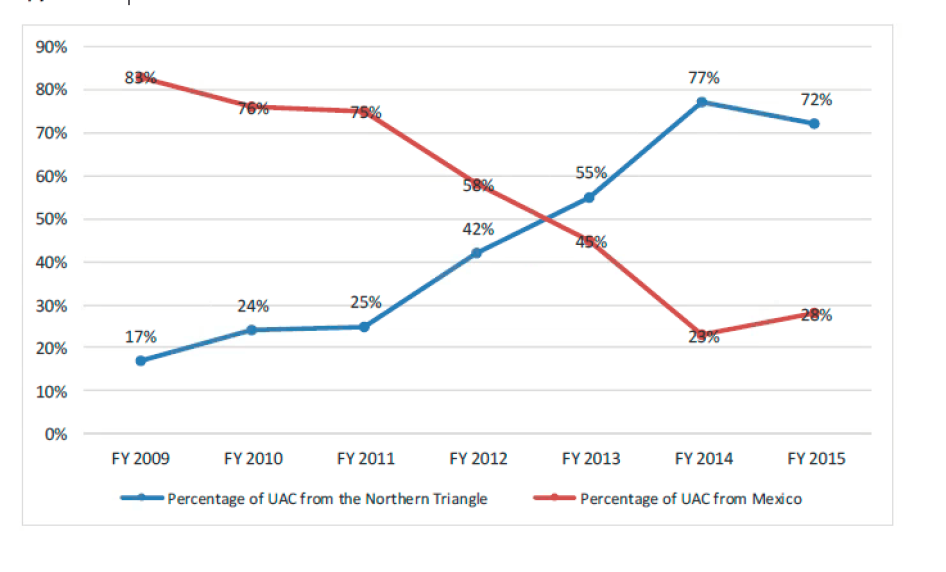

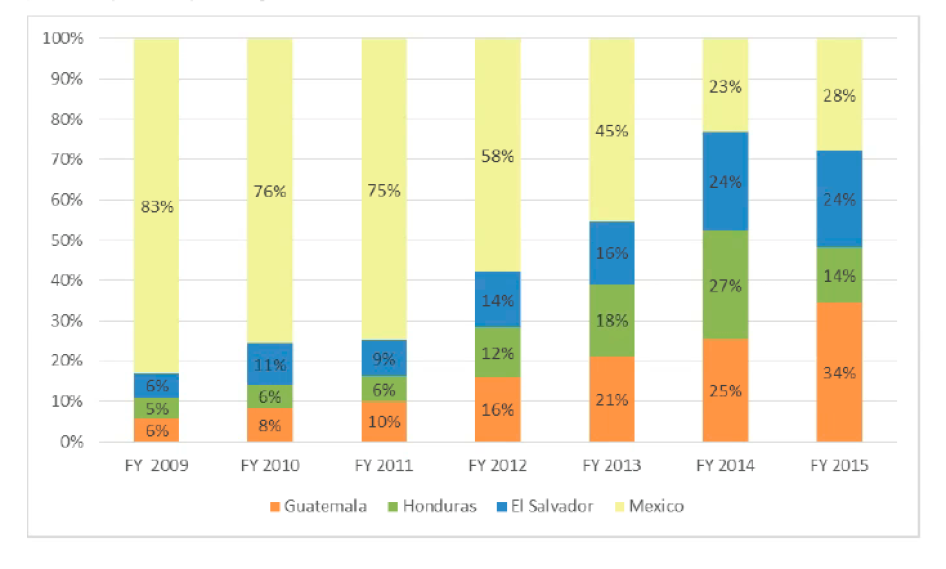

In addition, the profile of unaccompanied children apprehended along the US-Mexico border began to change after 2011. In each of FY 2009, 2010, and 2011, Mexican children made up three-quarters or more of all unaccompanied children apprehended at the US-Mexico border. Starting with FY 2012, unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras represented an increasing proportion of the total, and in FY 2014 and 2015 three out of four unaccompanied children apprehended along the US-Mexico border were from these three countries.[116]

Families from the three countries were also apprehended in significantly larger numbers during FY 2014.

CBP apprehended some 28,000 unaccompanied children from Central America’s Northern Triangle in FY 2015, a significant decrease from the 52,000 reported for the previous fiscal year but still more than the 21,000 apprehensions of unaccompanied children from these countries in FY 2013.

As measured by apprehensions, arrivals of Central American unaccompanied children again rose at the end of 2015. In October and November 2015, CBP apprehended 10,500 unaccompanied children along the US-Mexico border, more than double the number of such apprehensions during the same two months in 2014.[117]

US Promotion of Enforcement and Deterrence Measures

To address the increase in Central American arrivals, which he described as “an urgent humanitarian situation on both sides of the Southwest border,” US President Barack Obama requested Congressional authorization for $3.7 billion in emergency supplemental appropriations in July 2014, most of which would fund increased immigration enforcement, adjudication, detention, and other activities in the United States. A portion of these requested appropriations were for activities to be taken in Mexico and Central America, including “funding to address the root causes of migration” and “public diplomacy and international information programs.”[118]