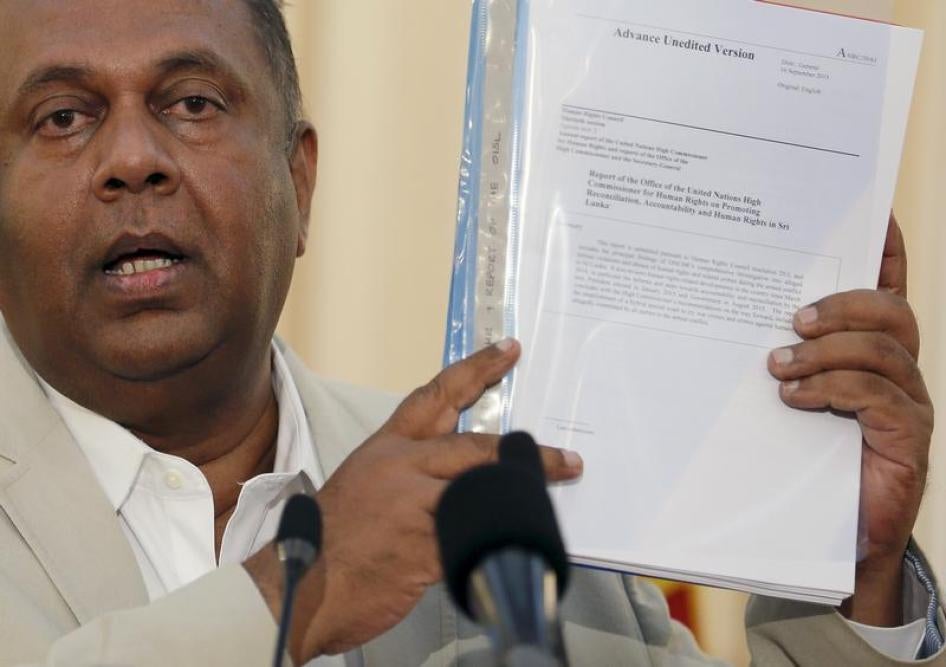

“Trust us,” Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, Mangala Samaraweera, told the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva just before the release of a landmark report into atrocities committed during the country’s long civil war, which ended in 2009.

The greatly anticipated report, by the UN high commissioner for human rights, details alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity implicating both government forces and Tamil Tiger rebels. The abuses include unlawful attacks on civilians, killings, enforced disappearances, torture, sexual violence, and recruitment of child soldiers.

The UN human rights chief flagged the need for “political courage and leadership” to tackle “deep-seated and institutionalized impunity,” which risks future violations. “Institutionalized impunity” has been allowed to fester for decades, he said, and the only way to effectively try past abuses in a highly politicized environment like Sri Lanka is to integrate international judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and investigators into a hybrid court – merging domestic and overseas expertise.

The victims of the conflict have waited years and even decades for justice. The report provides some hope that the Human Rights Council might finally make that possible.

Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena’s initial reaction to the report and its several dozen recommendations was cautiously receptive, a welcome change from his predecessor’s combative and dismissive approach. And hopes were raised when Samaraweera said, “Don’t judge us by the broken promises, experiences and U-turns of the past.”

But when the diplomats in Geneva met to negotiate a draft resolution on the report, Sri Lanka’s envoys returned to their old tricks.

The Sri Lankan delegation proposed amendment after amendment to the draft text, seeking to strip away all references to implement the report’s recommendations, including international participation in a justice mechanism and ending impunity. Virtually no paragraph was left unscathed. The delegation even suggested deleting proposals to ensure victim and witness protection, to investigate attacks on human rights defenders and journalists, and to address sexual violence and torture.

And the usual suspects, China, Russia, and Cuba – under the guise of “constructive engagement” – have endorsed Sri Lanka’s ignoble efforts.

Sri Lanka is asking the world to accept its promise to bring accountability as it sees fit. But trust must be earned. Against a decades-long backdrop of politically motivated interference and inaction on justice issues, there is simply no basis – whatever the sincerity of top officials – to be confident of Sri Lanka’s ability to deliver justice without a significant international role.

The main sponsors of this resolution, led by the United States, owe it to Sri Lankan victims – and to their own credibility – to properly deliver justice for these terrible crimes. To do otherwise risks leaving victims vulnerable to further violence and suffering. And they surely have already suffered enough.