Ntsikelelo is small for his age, and quite a handful. One moment, the 8-year old rolls around on the floor, the next instant he paces the room, impatiently and with big strides. The colorful picture books his mother has spread out on a low table hardly capture his attention. With a shrug he turns his back on them and walks off, shaking his head and waving his hand irritably -- a gesture that seems more befitting of a cantankerous old man than a wiry child.

His mother, a young woman with dreadlocks and a somewhat melancholic smile, watches attentively but lets him be. When offered a white sheet of paper, Ntsikelelo finally settles down, pen in hand and a sparkle in his big brown eyes. “I like writing my name,” he says and draws a row of uneven circles that float across the page like soap bubbles. “I like books,” he adds and points at the notebook in my hands. Under her dreadlock fringe Sisandua Hani’s face lights up with joy and pride.

She hasn’t always been proud of the boy, nor loved him. For years, the 29-year-old, who grew up in Orange Farm, an informal settlement just outside South Africa’s economic hub, Johannesburg, where unemployment and poverty are notoriously high, rejected her son. She berated herself for giving birth to a child who “was different from other children.” “He acted strangely,” she recalls, “tearing clothes, breaking things, threatening to burn the house down. ‘What is he doing?’ I asked myself time and again. ‘Why did God give me such a child?’”

Sisandua had fainted while giving birth and the newborn spent his first three months in an incubator, hooked up to a steady oxygen supply. When the baby boy finally came home, he started having fits. “His whole body would shake,” Sisandua remembers. “But he would not cry.”

Ntsikelelo was diagnosed with epilepsy – a neurological condition characterized by seizures - and with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder Syndrome (ADHD), which means that he is only able to concentrate for short periods of time. Both conditions are treatable. But instead of receiving extra attention to overcome his learning problems, he has – like hundreds of thousands of South African children with disabilities – been sidelined for being different and excluded from any kind of formal education for most of his young life. Today, he has no concept of shapes or colors, letters or numbers.

South Africa was one of the first countries to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and made a commitment to prioritize access to inclusive education for children with disabilities in its “Education White Paper 6.” However, 14 years later, this progressive policy that would guarantee children with disabilities the right to learn alongside their peers, has still not translated into equal opportunities or protection from discrimination for affected children, Human Rights Watch found in a new report, “South Africa: ‘Complicit in Exclusion’. Failures to Guarantee an Equal Right to Education for Children with Disabilities in South Africa.” This is especially true for children like Ntsikelelo, who come from a poor background and have a high need of support.

The government claims to have achieved the United Nations Millennium Goal of universal enrollment in primary education. But over half a million South African children with disabilities remain out of school because, Human Rights Watch research shows, schools often make arbitrary and unchecked decisions as to who can enroll, reliable data on how many children with disabilities remain out of school is lacking, and waiting lists are long.

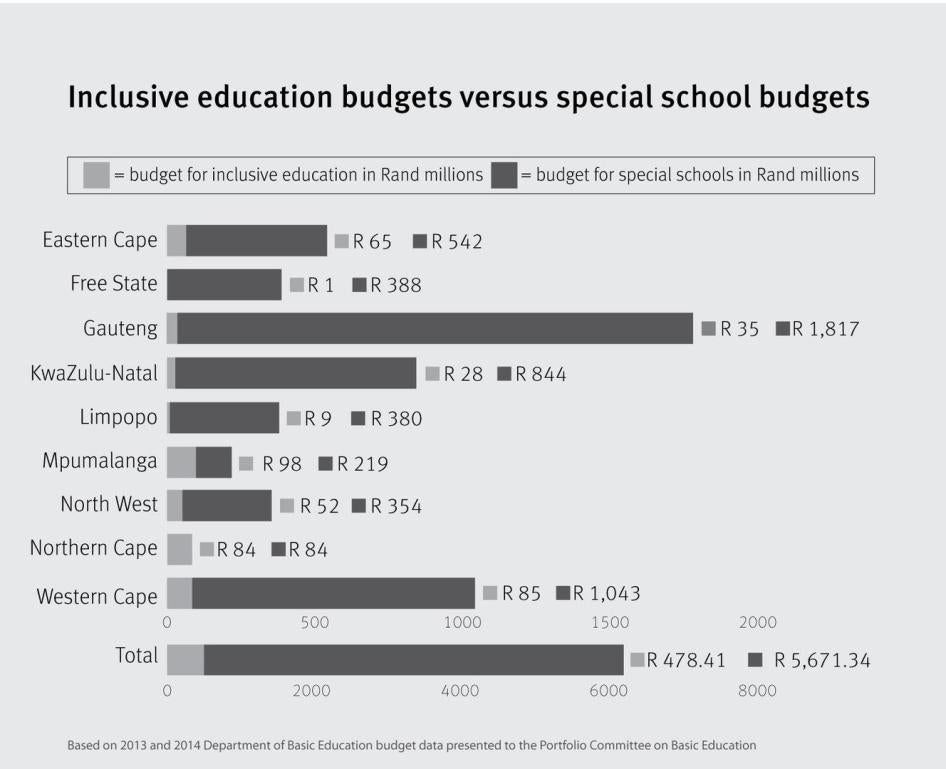

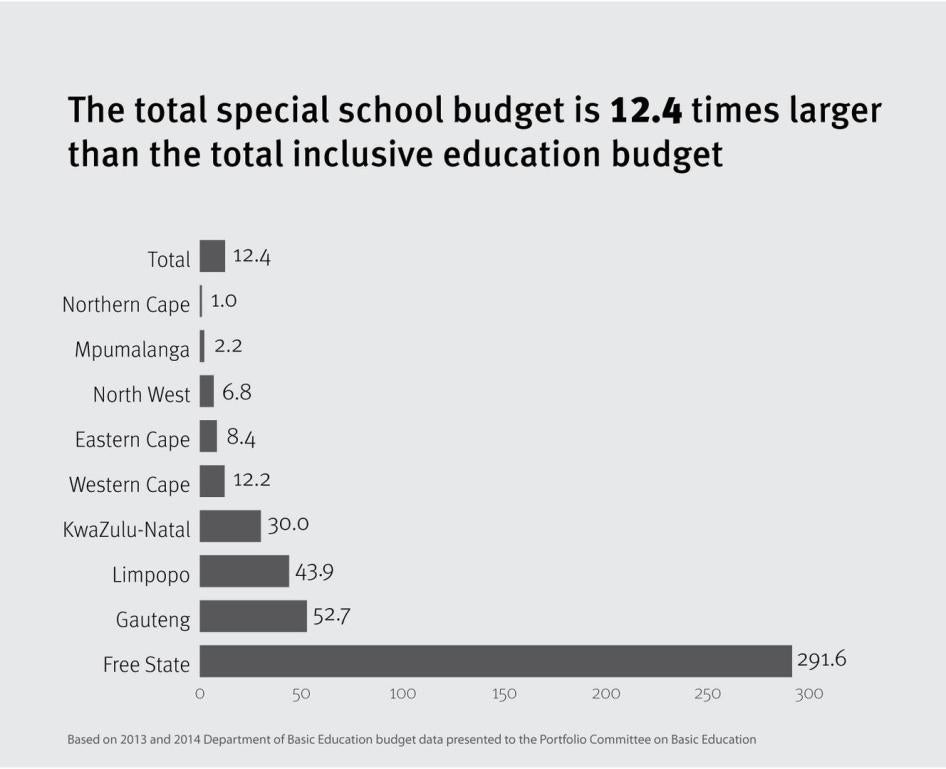

Many parents do not know their own rights, or are too afraid of stigmatization or further rejection to even try to insist on their children’s rights. To make matters worse, funding for inclusive education is inadequate. Human Rights Watch analysis found that over 12 times as much money is spent on expanding special schools: the government is in fact implementing a different policy than the one it set out in 2001.

Sisandua almost ended up destroyed by the lack of support and the widespread stigma attached to having a child with a disability. When other children started to call her son “egg-head” and mothers warned their toddlers not to play with Ntsikelelo because he could “infect” them, Sisandua responded with rage. She raged against his father: “You gave me this child.” She raged against her son: “I wanted to kill him.” And ultimately she raged against herself, drowning her despair in alcohol, partying to forget and loathing her body for having produced a child she could not love.

For a year and a half, Sisandua crashed on other people’s floors, abdicated all responsibility for her child and left her mother to cope with his temper, his fits, and his sleepless nights. When she finally came to terms with her fate and returned home, she found a happy 4-year-old boy who greeted her with a shy smile and the one word that melted her heart -- “Mama.” “I was the one who was useless,” she says. “He actually was a blessing to me.”

Ever since then, Sisandua has been fighting an often seemingly hopeless fight for a fundamental right: the right to education for her child. The day care Ntsikelelo attended at age 4 claimed not to have the necessary personnel to deal with his seizures. They advised Sisandua to keep him at home. The school she tried to enroll him in when he turned 6 gave him a number of tests, declared him unfit for mainstream schooling, and referred him to a training center for kids with special needs. The center put her name on a waiting list. And there it stayed.

It was only when Sisandua discovered Afrika Tikkun, a non-governmental organization that provides assistance and empowerment programs for parents of children with disabilities, that her confidence grew and with it her determination to find her son a school. Two years after her first attempt and after numerous visits to ensure her application had not been forgotten or lost, she finally succeeded. In January, Ntiskelelo had his first day at an ordinary public school. “This,” Sisandua says, “is the most amazing thing I did as a mother.”

Her success comes at a price, though. The costs of school fees and transport exceed what she earns cleaning houses or washing other people’s dirty laundry. If it weren’t for her mother, who rents out part of their whitewashed tin-roofed house to help pay the bills, she would not be able to keep her son at school. “Education should be free for all, but the government is not supporting us at all,” she says, and for a moment her usually composed expression shows a hint of irritation.

The self-help group Afrika Tikkun hosts in Orange Farm has not only restored Sisandua’s self-esteem. The group has also helped her understand her child better. “I now know how to handle him without losing my cool. And I can talk about him openly,” she says. “I could not do that at first.” Having once turned her back on her son, Sisandua is now at the forefront of those who encourage other women in a similar situation not to do the same. “They are surprised that I am not ashamed to talk about my child,” she reports. At least four mothers in her neighborhood hide their children indoors for fear of “what people might say” if they saw their disability. Sisandua knows them and talks to them regularly. After much prodding, one has joined Sidinga Uthando, the self-help group, and is finally able to share her experiences and learn about her and her child’s rights.

One day, Sisandua hopes, her son will be able to write his name and express himself about his condition, so that he does not get beaten up by big neighborhood boys for being different. Ntsikeleo, for his part, dreams of becoming a policeman, so that he can “lock up” those who harass him and his friends.

Tired of pen and paper, he jumps up and starts to re-enact a soccer match his mom once took him to, kicking and passing an imaginary ball while commenting on each player’s move as if he was reporting live from Orlando Stadium. Momentarily, the quiet room resonates with the roar and excitement of a Premier League’s match. “I love him more than anything,” says Sisandua, beaming. “I am a matured mother now, and a proud mother of a child with disabilities.”