(Berlin) – Recent amendments to Azerbaijani legislation violate the government’s international commitments and limit free expression. President Ilham Aliyev should veto the amendments and ensure that no one is punished for exercising fundamental rights.

One set of legislative amendments, adopted on May 14, 2013, by the Milli Majlis, Azerbaijan’s parliament, expand criminal libel laws explicitly to include statements made online. The amendments contradict Azerbaijan’s commitments to decriminalize libel, Human Rights Watch said. Another set of amendments significantly increase jail terms for minor public order offenses, such as failing to comply with rules on holding demonstrations.

“The new amendments impose wholly disproportionate and unjustified punishment on people who want to express themselves, whether online or on the streets,” said Giorgi Gogia, senior Europe and Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Unless they are vetoed, the amendments will have a chilling effect on the rights to freedom of expression and assembly, violate Azerbaijan’s international obligations, and shut down opportunities for legitimate dissent.”

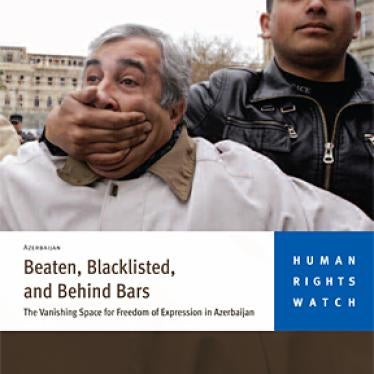

The amendments come amid a crackdown on freedom of expression, assembly, and association in the lead up to the October 2013 presidential elections. They follow months of police suppression of peaceful protests and arrests of political opposition activists, social media activists, and human rights defenders, and other government critics.

The first set of amendments expand the definition of slander and insult, set out in articles 147 and 148 of the Criminal Code, specifically to include content “publicly expressed in internet resources.”The sanction for slander and insult can be up to 480 hours of public service, after amendments in April doubled the maximum number of hours. The maximum prison sentence for slander, the more serious offense, is three years.

Azerbaijan’s human rights National Action Plan, approved by Aliyev in 2011, envisaged the decriminalization of libel, and in 2012 the presidential administration wrote to the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission requesting assistance in drafting relevant new defamation provisions. A January 2013 resolution adopted by the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly urged the Azerbaijani government to “elaborate a new law on defamation in co-operation with the Venice Commission,” the Council of Europe’s advisory panel on constitutional matters.

“After 18 months of government rhetoric on decriminalization, the amendments are a shocking setback and a betrayal of its international commitments,” Gogia said. “Azerbaijan should move forward, not backward, on decriminalizing libel.”

The amendments’ specific reference to insult and slander in online materials is unnecessary and alarming, Human Rights Watch said.

The existing provision made no reference to the types of media for which insult and slander may be penalized, and the 2001 Law on Mass Media defined mass media as including the Internet. At least one journalist in the past six years was convicted of criminal slander under the previous definition for an online statement attributed to him.

“It’s difficult to avoid concluding that the Azerbaijani authorities proposed these amendments to intimidate Azerbaijan’s online activists and stifle critical expression,” Gogia said.

A 2010 Human Rights Watch report on Azerbaijan found that most television stations have close ties to the government. It found that criminal libel charges, overwhelmingly pursued by the public officials, as well as prohibitive civil defamation suits and other repressive government actions, are crippling key independent and pro-opposition print media. This left the Internet as the last remaining haven for independent free expression, Human Rights Watch said.

The other set of amendments, to the Code of Administrative Offenses, sharply increase prison terms for administrative, or misdemeanor, offenses. That includes charges the government frequently uses to punish people for involvement in peaceful, albeit unsanctioned, public protests. The maximum jail sentence for violating rules for organizing, holding, and attending unauthorized assemblies increased from 15 days to two months.

Earlier amendments, adopted in November 2012, dramatically increased monetary sanctions for participating in and organizing unauthorized protests, establishing fines of up to 1,000 AZN (US$1,274) for participation and 3,000 AZN (US$ 3,822) for organizing.

The May 14 amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses also increased the maximum sanction for disobeying a police order, an infraction often leveled against protesters, from 15 days to one month. Failure to carry out court-ordered public service, a sanction often imposed on protesters, carries a maximum jail term of three months.

The amendments also increase jail terms for certain administrative offenses relating to traffic rules, hooliganism, and other infractions, but they are clearly aimed at tightening the government’s effective ban on all forms of peaceful protest from the center of Baku, Human Rights Watch said. Since early 2006, authorities have not authorized a single opposition protest in the center of Baku, and instead sought to force all demonstrations into designated zones on the outskirts of the city.

Such a blanket ban against freedom of assembly in the central areas of Baku goes against Azerbaijan’s international commitments to freedom of assembly and expression, Human Rights Watch said. As the European Court of Human Rights has warned, “Sweeping measures of preventive nature to suppress freedom of assembly and expression … do a disservice to democracy and often endanger it.”

The amendments also undermine the fair trial rights of detainees, Human Rights Watch said.

Hundreds of peaceful protesters have been sentenced to jail time under the Code of Administrative Offenses in recent years. In cases Human Rights Watch documented in 2011 and 2012, trials were perfunctory, some lasting barely more than 10 minutes; detainees were not allowed to retain a lawyer of their own choosing; and in some cases hearings were effectively closed to the public.

Because the potential punishment for administrative offenses amounts to a criminal penalty, anyone facing administrative charges should have the same rights to due process, fair trial norms, and protections against arbitrary detention that people do when they are charged under the criminal code, Human Rights Watch said.

The European Court of Human Rights has ruled that countries with a system of administrative detention have an obligation to provide adequate due process and fair trial protections to meet the standards required by the European Convention of Human Rights.

“The new jail terms amount to a criminal penalty, but by no stretch of the imagination do administrative detainees get full due process rights,” Gogia said.