(New York) – Yemeni security forces have arbitrarily detained dozens of demonstrators and other perceived opponents of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh since anti-government protests began in February 2011, Human Rights Watch said today. Human Rights Watch documented 37 cases in which security forces have held people for days, weeks, or months without charge, including 20 who were picked up or remained behind bars after the November 2011 power transfer.

Twenty-two former detainees told Human Rights Watch they were subjected to torture and other ill-treatment, including beatings, electric shock, threats of death or rape, and weeks or months in solitary confinement. Human Rights Watch also interviewed relatives of five protesters, opposition fighters, and others who remained forcibly disappeared or held without charge, as well as two people being held in an unregistered jail by the First Armored Division, which defected to the opposition in March 2011. Human Rights Watch called on both government and opposition forces to immediately release everyone they are still arbitrarily detaining.

“There’s no serious prospect for a new era of respect for human rights in Yemen as long as security forces can detain anyone they want, outside any semblance of a legal process,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “The transition government should ensure that all security forces immediately get out of the illegal detention business.”

During a Human Rights Watch visit to the capital, Sanaa, in March and early April, local human rights groups and officials from both Saleh’s party and the opposition alleged that many protesters, fighters from both sides, and others apprehended during the uprising were still being held incommunicado. Government and opposition security forces denied to Human Rights Watch that they were unlawfully detaining anyone but each accused the other side of doing so.

Saddam Ayedh al-Shayef, 21, one of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch, said men he believes were from the government’s National Security Bureau grabbed him from a street in Sanaa on March 4, 2012, and drove him blindfolded to prisons in Sanaa and Aden, where they repeatedly tortured him during a week of incommunicado detention.

“They made me drink my own urine,” he said. “When I refused to drink it, they electrocuted me. After I came home, I would dream I was still being tortured and I’d wake up screaming.”

Because of limited public information and lack of access to detention facilities, Human Rights Watch has been unable to determine how many people have been or remain detained without charge. Prime Minister Muhamed Salim Basindwa reportedly could not provide a number to youth protesters who met with him on April 12, 2012 to discuss the issue. One prominent official close to former president Saleh told Human Rights Watch that authorities were still holding at least 100 people.

Human Rights Watch called on the new government of President Abdu Rabo Mansour Hadi to immediately make public a list of all detainees in the country.

Saleh began transferring power to a transition government on November 23, and Hadi became president following an uncontested vote on February 21. In January, Yemen’s caretaker cabinet and a military restructuring committee, headed by Hadi who was then the acting president, ordered the release of all arbitrarily detained prisoners. Both government and opposition security forces freed scores of detainees.

Between February and April, Human Rights Watch interviewed 23 former detainees in Sanaa who were arbitrarily detained in 2011 and early 2012, as well as the relatives of five current detainees and one former detainee. Those detained included anti-government demonstrators, fighters from opposition forces, a human rights defender, and residents of Taizz, Nehm and Arhab, where government forces have clashed with tribal fighters. In February 2011, Human Rights Watch also documented eight cases of enforced disappearance of activists with the Southern Movement, a coalition seeking greater autonomy for southern Yemen.

The former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were held from a few days to 10 months by security and intelligence units including the Republican Guard, the Political Security Organization (PSO), the National Security Bureau (NSB), and the Central Security Organization (CSO). All of these units are run by Saleh relatives and loyalists and, despite Saleh’s departure, are still operating largely outside of central government control.

One Presidential Guard officer who defected to the protest movement was taken by fellow Presidential Guards and held for three weeks in February and March 2012 in a cell inside the presidential palace, a relative said.

The two men detained by the First Armored Division were being held in March, when the division was continuing to guard areas around Change Square, a sprawling protest camp in Sanaa, while also guarding President Hadi’s house. Government officials and some human rights defenders accused the First Armored Division of unlawfully holding hundreds of perceived government loyalists during the uprising. Human Rights Watch also found that members of the opposition Islah Party were operating an unauthorized jail inside Change Square.

Most former detainees were denied access to lawyers and relatives for most or all of the time they were detained. Several former detainees said they were blindfolded when they were brought to detention centers so they would not know their whereabouts.

An immunity law that Yemen’s parliament enacted on January 21 grants blanket amnesty to former president Saleh and immunity for “political” crimes to all those who served with him during his 33-year rule. However, the law does not preclude prosecutions of those responsible for arbitrary detentions, Human Rights Watch said. The law violates Yemen’s international legal obligations to prosecute serious violations of human rights and does not shield officials from prosecution for offenses committed since its enactment, Human Rights Watch said. Human Rights Watch documented 14 cases of arbitrary arrests and continued detentions without charge after the law was passed.

The United States, European Union, and Gulf states should call for the transfer of all detainees to judicial authorities so they can be freed or charged and prosecuted in impartial and fair proceedings, Human Rights Watch said.

“Reining in Yemen’s security forces won’t be easy but it’s key to instilling rule of law in the country,” Whitson said. “Concerned governments should press all sides to free wrongfully held detainees, and ensure those responsible are held accountable.”

Abuses by Yemen’s Security Forces

Torture and Ill-Treatment

Most of the 23 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Yemen described being subjected to torture and other ill-treatment while in custody. Sixteen said they were subjected to electric shocks, whippings, beatings, or being hung from ceilings. Six others described threats of death, rape, or harm to their relatives. One man said Republican Guards strapped him to what he thought was a cannon while it was being fired. Several said they were held for weeks or months in solitary confinement.

Muhammad Abd al-Karim al-Godyili, 29, of Arhab, an area 35 kilometers north of Sanaa where Republican Guards and tribal opposition fighters battled in 2011 and where sporadic clashes continue this year, alleged he was tortured and threatened with death during his detention at two Republican Guard posts from July 25 to January 13. He said the worst treatment was during his first month at the 62nd Brigade post in Arhab:

They would take me and the other prisoners out and tie us to a light pole and fire bullets past us, saying it was target practice. Every night they would tell us that the next day we would be killed.

Many former detainees said they were imprisoned in filthy, insect-infested cells that in some cases were so small that they could not sleep fully extended. Several said they were held in isolation and denied access to light, fresh air, or sufficient water and food. Nearly all said they were denied communication with relatives or lawyers for all or most of their detention. Some said they were denied medical care or that they had lasting injuries from torture.

A member of the elite Presidential Guard who had joined the protest movement was held incommunicado in the presidential palace for nearly three weeks during a period that included the February 21 balloting to elect Hadi and the February 25 presidential inauguration, a relative told Human Rights Watch. Images of Yahya Ali Yahya al-Dheeb riding on the shoulders of protesters in his red beret and Presidential Guard uniform had appeared in Arabic and English-language media after his defection in early 2011, making him a symbol of the anti-Saleh movement.

Soon after joining the protests, al-Dheeb, 28, began receiving threatening phone calls, said the relative, so he remained at Change Square until Saleh signed the November agreement to cede power. Al-Dheeb then returned to his family and began work as a taxi driver, assuming he was no longer in danger. On February 11 he did not return home. A witness later told al-Dheeb’s family that on February 11 Presidential Guards greeted al-Dheeb by name when he approached a checkpoint at al-Musbahi Square in his taxi and then detained him.

“We contacted his colleagues,” the relative said. “They said, ‘His car is inside the presidential palace but we don’t know where he is.’”

The family tried unsuccessfully to secure al-Dheeb’s release through cabinet ministers and members of parliament. Al-Dheeb was finally released on March 6 through the efforts of a sheikh with close ties to Saleh, the relative said.

Emad Ahmad al-Shulaif, 25,a First Armored Division soldier, was held by the Republican Guard from November 7 for 16 days at the Beit Dahra barracks of the 63rd Brigade near Arhab. He told Human Rights Watch that his captors applied electric shocks to his genitals with such force that doctors told him he has little chance of fathering children.

“I thought I was going to die,” al-Shulaif said. “But worse than the pain is knowing I may never have a family.”

Some former detainees said their captors stole their money and possessions, or that they were released only through the intervention of influential friends or relatives. Munir Naji Abaad, 18, a resident of Nehm who was detained from July 24 to August 1 at the 63rd Brigade barracks, said he bought his freedom by “giving” his motorcycle to his captives. He said the soldiers also took his jambiya, the traditional Yemeni dagger, and all his cash.

Many detainees said they were taken at Republican Guard or Central Security checkpoints because they lived in opposition strongholds such as Arhab, Nehm, or Taizz, a former Yemeni capital, or because they carried cards identifying them as members of protest groups. Arhab and nearby Nehm are only 35 kilometers from Sanaa, but residents were so fearful of being detained again that they traveled a circuitous route of more than 250 kilometers, dodging numerous checkpoints, to meet with Human Rights Watch.

Samid Abd al-Jalil al-Qadasi,24, an unemployed chemistry graduate from Taizz, said he was detained for five weeks after Central Security forces discovered from his identity card that he had been a paramedic at the field hospital in Sanaa’s Change Square, treating people wounded during attacks by government forces and pro-government gangs. Central Security is headed by Yahya Saleh, the former president’s nephew.

Al-Qadasi said a small group of Central Security forces stopped him and other passengers the night of September 24 in the Asser district of Sanaa as they disembarked from a bus from Taizz. He said he hid his identity card in his sock. The officers searched him once they learned that he was from an opposition neighborhood in Taizz and that his cellphone service was with Sabafon, a company owned by Hamid al-Ahmar, an influential Yemeni whose family played a key role in the uprising.

“As soon as they found the identity card in my sock, they beat my head with the butt of a gun and kicked me with their boots,” al-Qadasi said. He showed Human Rights Watch a scar on his temple that he said was from the beating.

Al-Qadasi said the Central Security forces took him to their headquarters on 70 Meter Street, blindfolded him, held a gun to his neck and threatened to kill him. Then they began beating him with a cable while interrogating him until dawn about the Change Square hospital in Sanaa:

They were asking, “What do you do at the hospital?” “Who funds the hospital?” “Are those martyrs shown on [opposition-run] Suhail TV real or fake?” All this time my head was bleeding from when they hit me with the gun. Finally around 5 a.m. a doctor gave me stitches.

Al-Qadasi said that after they questioned him, his captors took him to a cell that contained more than 30 other detainees. Most, he said, told him they had been detained because they had protester identification cards. One man said Central Security grabbed him after noticing that his key chain was decorated with the image of Tawakkol Karman, a Change Square protest leader and 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner. Al-Qadasi spent the rest of his detention in the General Security police station in the Habra district of Sanaa. He was able to inform his family of his whereabouts only by bribing a guard to use his cellphone.

Saddam Ayedh al-Shayef, 21, a student protester and the son of a sheikh allied with a commander of the renegade First Armored Division, said he believes the National Security Bureau was responsible for his forced disappearance and torture. He said his captivity began on March 4, 2012, as he left a mosque in Sanaa. Three or four men in civilian clothes asked him to help them push their car, then forced him into the vehicle, blindfolded him, and drove him for several minutes to his first place of detention.

A day-and-a-half into al-Shayef’s captivity, his father, Ayedh Muhammad al-Shayef, received a tip from an intelligence official that his son was being held by the NSB. The father told Human Rights Watch that he contacted NSB officials and demanded they release his son. Saddam al-Shayef said that on the same afternoon, his captors blindfolded him again, placed him in a vehicle, and drove him several hours to another detention center. The father and son learned the sequence of events only after they compared notes following the son’s release.

The son said the worst torture took place in the basement of the second detention center. There, he said, two men in civilian clothes applied electric shocks to his arms and back and burned his arms with cigarettes as they interrogated him about his father’s relationship to General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, the First Armored Division Commander. He showed Human Rights Watch more than 20 fresh scars on his arms that appeared to be cigarette burns. The guards would arrive at seemingly random hours, he said:

They would come in, apply electric shocks, burn me with cigarettes, and beat me. They spit their qat [a plant that many Yemenis chew as a stimulant] into my food. They made me drink my own urine. When I refused to drink it, they electrocuted me. … I lost track of time. I was praying to God and thinking of my dad and my mom.

On March 10, he said, his captors again blindfolded and handcuffed him, and placed him on the back of a motorcycle. He was driven for 15 minutes and dumped on the side of an isolated road. After managing to remove his blindfold, he walked for an hour until he met two passersby, who told him he was on the outskirts of the city of Aden, 300 kilometers south of Sanaa, and helped him call his family.

Hemyar Derhem al-Moqbeli, 26,an unemployed accountant who was active in the anti-Saleh protests in Sanaa, said he was detained inside NSB headquarters in the capital from October 24 to December 12. He was again detained at a secret location from January 12 to 25. He said the questions of his interrogators led him to believe that it was also the NSB that held him the second time. During both detentions his questioners accused him of working as financial coordinator for the protest movement and demanded details on who was funding the demonstrators. He said they also told him during the January detention: “This is the second time we are interrogating you. The third time you will never see daylight again.”

Both times, al-Moqbeli said, he was tortured. In the NSB headquarters, he was blindfolded and beaten with some kind of stick until it broke with a bang:

They would say, “Do you know what this is?” I would say no. They would say, “You’ll find out what it is if you don’t talk.” The first night was the most terrifying. I had never before been detained for anything, and all of a sudden I am blindfolded and being asked, “Why did you go against Ali Abdullah Saleh?” I felt like it was the end of the world.

Al-Moqbeli said he was picked up again on January 12 as he went to a foreign currency dealer near Change Square. Apparently suspecting he had received funds for the protest movement, men in civilian clothes forced him into a car, blindfolded him, and drove for about 30 minutes to a building where he was held for 13 days. He told Human Rights Watch:

They put me in a cell without blankets. It was very cold. I asked for a blanket. The guard said, “You want a blanket?” He blindfolded me again, poured cold water all over me and locked me in a bathroom overnight. I had to remove my clothes because they were wet. The next day he took me back to my cell and brought me a thin mattress but no blanket. I got so sick I was fainting. But I didn’t dare ask for a blanket again.

After one interrogation session, al-Moqbeli said, his captors hung him from the ceiling for several hours with the tips of his toes barely touching the floor.

One former detainee, who asked that Human Rights Watch withhold his name and the unit that held him for fear of retaliation,described himself as “lucky” not to have been tortured, but said the psychological pressure during his detention from July to March was “unbearable.” He said:

I could hear people being beaten. Then I would hear their moaning and vomiting. For months, I was not able to see the sun. When I was sick I was not provided medicine. I could not call my family. I was not even allowed to read. My weight dropped from 89 kilos to 50 kilos.

Enforced Disappearances

Human Rights Watch interviewed relatives of five people still being detained without charge who are or were being held incommunicado or are feared to have been forcibly disappeared. They include First Armored Division soldiers, suspected fighters from opposition areas, and anti-government protesters. In four of these cases, relatives or other witnesses saw the person being abducted or learned of their whereabouts through influential contacts or former detainees who had seen them in captivity. In January, the authorities confirmed that they are holding two of the five, but have not publicly acknowledged whether they are holding the other four.

Under international law, a government’s refusal to acknowledge that a person has been detained or to reveal the person’s whereabouts following detention or arrest by state forces is an enforced disappearance. Enforced disappearances often facilitate torture or custodial killings, and the lack of knowledge of an individual’s fate is especially damaging to the victim’s family.

During the meetings with Human Rights Watch in March, security and intelligence forces insisted they were not unlawfully holding anyone and each accused rival forces of doing so. Gen. Ahmed Ali Saleh, the former president’s son and commander of the Republican Guard, gave Human Rights Watch a list of 80 soldiers he said had been captured by the renegade First Armored Division. Gen. al-Ahmar, the First Armored Division commander and a longtime rival of General Saleh, accused the Republican Guard of holding dozens of his men.

Family members of two other Change Square protesters said they or other witnesses saw armed men in civilian clothes grab the men and drive them into the Political Security Organization headquarters in Sanaa in two separate incidents on December 5. Pro-Saleh media announced the men’s arrest days later, calling them terrorists. But they have not been charged, and PSO officials have alternately confirmed and denied to relatives that they are holding the men, although they told Human Rights Minister Mashhour in January that they were in their custody.

Around midday on December 5 about 15 armed men surrounded Muhammad Mothana al-Ammari, 32, as he left his father-in-law’s house with his wife and young son, forced him into a silver sport utility vehicle, and drove him into the PSO parking lot, which was near al-Ammari’s house, according to family members, who said they saw the entire incident.

Al-Ammari, who taught the Qur’an to foreigners, had been active in Change Square during the early days of the protests, relatives said. He began receiving threats from PSO officers, who held him for a half-day in March and warned him to stay away from the protests or risk harm to himself and his family.

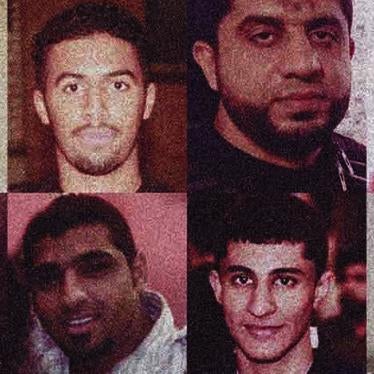

On December 15 the pro-government newspaper Al-Thawra ran a front-page article with the headline, “Six Terrorists from al-Qaeda” that featured photos of six men, including al-Ammari, and quoted a government source who described them as dangerous armed militants seized by the authorities. But al-Ammari’s wife, Ahlan al-Ariqi, told Human Rights Watch that when she went the next morning to PSO headquarters, officials there denied they had the men:

For weeks they denied they had him. They would call us and harass us and say they had news for us. Then when we would show up to find out the news they would again tell us nothing. Finally on February 11 an official at Political Security told us, “He is here but you cannot see him yet. We will call you when you can see him.” I waited for days but they never called. I went back on February 23 [two days after President Hadi’s election], and they again denied they had him.

All the family wants is for al-Ammari to be judged according to the law, Abd al-Halim al-Ariqi, al-Ammari’s father-in-law, told Human Rights Watch.

“If my son-in-law is a criminal, prosecute him, but if he is innocent, set him free,” al-Ariqi said. “I voted for President Hadi because I want him to bring justice to Yemen, not to continue the old system.”

Nadir Ahmad Muhammad al-Qubbati, 30, a computer programmer for the government’s taxation office who had joined the protests, was also named in the Al-Thawra article as a terrorist. Armed men seized him on December 5, said his wife, Maha Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Duba’i. She said a witness told her that her husband was riding a minibus with a colleague around 11 a.m. when two men who had been trailing them in a silver sport utility vehicle boarded the mini-van and forced them out at gunpoint.

The gunmen drove the two men to Political Security headquarters in Sanaa and kept al-Qubbati but released his companion, the witness told al-Qubbati’s relatives. When al-Qubbati’s relatives inquired at Political Security, the officials kept changing their story about whether they were holding him. Maha al-Duba’i, his wife, told Human Rights Watch:

They would play with our nerves. They would tell us, “Come back in a few days,” and then when we did, they would tell us, “We don’t have him.” When other prisoners were released earlier this year, we thought he would be one of them. We were counting the hours. But he didn’t come.

Maha al-Duba’i said that on September 20, months before her husband was abducted, a sniper shot dead her brother, Hamza Muhammad ‘Abd al-Rahman Al-Duba’i, during an attack on protesters at Kentucky Roundabout in Sanaa. “To this new government I say, I have lost my brother, please give me back my husband,” she said to Human Rights Watch.

One family told Human Rights Watch of searching for one missing relative while mourning another killed in anti-government protests. On June 28, Majid Mansour ‘Abdu Hamoud Ghar-Allah, 23, dropped from sight in what his family believes was an abduction by pro-Saleh security forces. A driver with a government employees’ union, Ghar-Allah had increased his participation in protests after his brother was killed in an attack on a demonstration in Sanaa in March 2011.

Relatives said a union supervisor had fired Ghar-Allah without pay on June 27 after another union member reported seeing him heading to Change Square. The following day, Ghar-Allah vanished after saying he was returning to the union to demand his wages. About nine weeks later, Ghar-Allah phoned his sister from a land line and said, “Please tell my father I am okay,” and hung up, his father, Mansour ‘Abdu Hamoud Ghar-Allah, told Human Rights Watch. The family has heard nothing more.

The father looked for his son everywhere: “I searched for him at hospitals, police stations, Political Security. I printed more than 5,000 posters of him and sent them to the media. I appealed for his release on television. Nobody responded.”

Ghar-Allah’s brother Mu’ath Ghar-Allah, 24, was among 45 protesters shot dead by pro-government snipers in Sanaa on March 18, 2011.

“I want the government to give me back my son if he is still alive or give me back his body if he is dead,” Ghar-Allah’s father said. “If they give me all of Sanaa, it is not enough to make up for his loss. But if he came back, it would remove part of the pain over the death of my other son.”

Access to Detainees and Unregistered Detention Centers

Some security forces and intelligence agencies have denied government officials and lawyers access to their detention centers, further hindering efforts to account for people held arbitrarily. For example, Human Rights Minister Hooria Mashhour told Human Rights Watch that agencies including PSO and NSB will not let her visit their prisons. Based on meetings with relatives of forcibly disappeared people and human rights activists, Mashhour said, she believes dozens of detainees are still being held arbitrarily, including by sheikhs and opposition forces.

Prosecutor General Ali Ahmad Nasser al-Awash, a holdover from the Saleh administration, told Human Rights Watch that registered jails unlawfully held large numbers of protesters and other detainees during the 2011 uprising. Jail authorities would release the detainees on his orders but “within a month the jails would be full again,” he said.

The PSO and NSB jails are not registered detention centers as required by article 48(b) of the Yemeni constitution. The NSB and PSO reported to Saleh and their loyalties remain unclear.

The PSO is detaining 28 people in Sanaa in connection with a deadly attack on the presidential palace in June that seriously wounded Saleh, according to lawyers with the Yemeni Organization for Defending Rights and Freedoms (HOOD), which represents the suspects. Most of the suspects were held in secret detention for seven months before their captors moved them to Political Security and formally charged them in February, the lawyers said. Four detainees released in January and March were not suspects but were being unlawfully held as hostages by authorities seeking their fugitive relatives in connection with the bombing.

Prosecutor-General al-Awash told Human Rights Watch that he “believed” that the PSO and NSB continued to hold without charge persons whom authorities suspected of “terrorism.” When Human Rights Watch asked him to elaborate, he replied: “You are asking too many questions.” Ali Mohamed al-Anisi, the director of National Security and a longtime Saleh ally, denied the NSB was holding prisoners or operated any prisons. The PSO did not grant Human Rights Watch’s request for a meeting.

Unlawful Detentions by the Opposition at Change Square

Since at least December, a security committee formed by members of the Yemeni Congregation for Reform (Islah), Yemen’s most powerful opposition party, has unlawfully detained people in a jail in Change Square. Human Rights Watch saw two prisoners inside the cell during a visit on February 28. Islah members initially formed the committee to help protect protesters from government attacks and to provide security within Change Square.

On December 4 guards appointed by the security committee beganberating and hittingthree Yemeni human rights defenders who were videotaping statements from detainees in the jail. The human rights defenders posted a videotape of the attack on YouTube. One videotaped detainee, who claimed to be a renegade Republican Guard, said that his Change Square captors had jailed him for 10 days, forced him to clean the streets of the square in the middle of the night, and doused him with cold water.

Mua’adh al-Shami, a security committee member who was guarding the jail the day Human Rights Watch visited, acknowledged the jail regularly held detainees but denied abuse. “This is not a jail but a place to solve problems,” al-Shami said.

Al-Shami said the committee used the jail to detain thieves, brawling protesters, people unlawfully carrying weapons, and government infiltrators. He said the committee turned over the detainees implicated in crimes to the local police, but that the police promptly released them, allowing them to return immediately to Change Square. In the past, he said, the committee transferred some people taken into custody to the First Armored Division.

Yemeni human rights defenders told Human Rights Watch that the security committee has detained protesters critical of Islah – an allegation al-Shami denied.

Human Rights Watch also heard complaints that the First Armored Division appears to have been holding criminal suspects, although General al-Ahmar denied this allegation. On March 21 Human Rights Watch saw two men locked inside a building in a neighborhood of Sanaa controlled by the First Armored Division. The men, speaking through a grate above a barred door, said that the First Armored Division had detained them at the site for three days for consuming alcohol, which is against the law in Yemen. A witness said that the First Armored Division on several occasions had used a classroom in the 26 September School in Sanaa, which its troops occupied as recently as March, as a detention center.