On 7 March, after vociferous domestic opposition and the intervention of European Union institutions, the Hungarian parliament amended a controversial and restrictive media law that would have severely curtailed free speech.

For some observers, these amendments closed a contentious chapter that had tainted Hungary's presidency of the EU. For others, they represented a successful example of EU intervention with a member state to enforce common standards.

The reality is more complex. On 15 March more than 10,000 protesters took to the streets of Budapest to demand greater reforms to the media law. The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe's media freedom representative, as well as numerous non-governmental organisations in and outside Hungary, have pointed out that the amendments did not go far enough to ensure that Hungary's media may operate freely.

The amended law still subjects media outlets based in Hungary to regulation by politically homogeneous government-appointed media bodies. The amendments still allow broad and vague restrictions on how and what the media may say, including a prohibition on publications that may incite hatred or social exclusion directed against the majority.

The amendments still allow large fines for violating these vague restrictions. The assurance from the president of the new Media Authority that the purpose of the legislation is "prevention rather than punishment" does little to allay concerns that the restrictions will chill critical reporting.

The media legislation is part of a troubling trend in human rights in Hungary.

Violence against Roma by individuals and vigilante groups is increasing, without adequate government response.

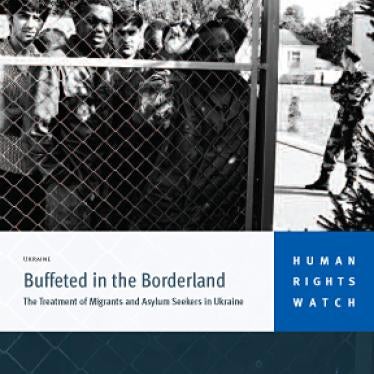

As Human Rights Watch has reported, migrants from third countries entering through Ukraine have been quickly returned there, despite evidence of ill-treatment in detention in Ukraine, in some cases after their pleas to seek asylum in Hungary were ignored.

A new asylum law allows for the extended detention of asylum seekers and other migrants. And domestic human rights organizations report that, since the ruling Fidesz party won a two-thirds majority in parliament in April 2010, the rights groups' efforts to engage in dialogue with the government have been largely ignored.

Until it amended the media law, the government had resisted internal and external pressure for reform. Indeed, Prime Minister Viktor Orban insisted that Hungary would not be dictated to by the EU or anyone else. But in the end, Hungary did respond to international pressure, particularly from Brussels, to amend the media law.

Resolutions by the European Parliament and an ultimatum from the European Commission to address its concerns with the law or face possible infringement proceedings made the cost of not amending the media law higher than the benefits of standing behind it.

The European Commission deserves credit for acting swiftly to press Hungary to abide by EU standards, including the rights to free expression and media freedom contained in the Charter of Fundamental Rights. But the EU also bears some responsibility for the incomplete nature of the reforms.

The strong letter sent by the media commissioner, Neelie Kroes, in January outlined the commission's concerns, including those related to breaches of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and threatened to send a letter of formal notice (the first step in infringement proceedings) if they were not met. But the amendments proposed by Hungary, and accepted by the commission, did not fully address its concerns.

As an apparent substitute for demanding full reform, the commission has said it will monitor the media law to ensure that Hungary does not run afoul of European legislation.

By contrast, the European Parliament has continued to press for complete reform of the law itself, passing a new resolution on 10 March stating that Hungary had not gone far enough.

Much of the noise about the media law arose because it came into force at the moment that Hungary assumed the EU presidency. When Poland assumes the presidency in July, there is a risk that interest from Brussels in monitoring Hungary's actions toward the media could wane, even if problems with the legislation and its implementation persist.

As the commission's response to France's expulsions of Roma EU citizens last summer illustrates, it can shy away from protracted disputes with member states over human rights.

To avoid that outcome, the European Commission should use the second half of Hungary's EU presidency to ensure that the media law and its implementation comply with the principles enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and media directives. And together with the European Parliament, it should keep a sharp eye on Hungary's general record on rights, even beyond the current EU presidency.

Amanda McRae is the western Balkans researcher at Human Rights Watch.