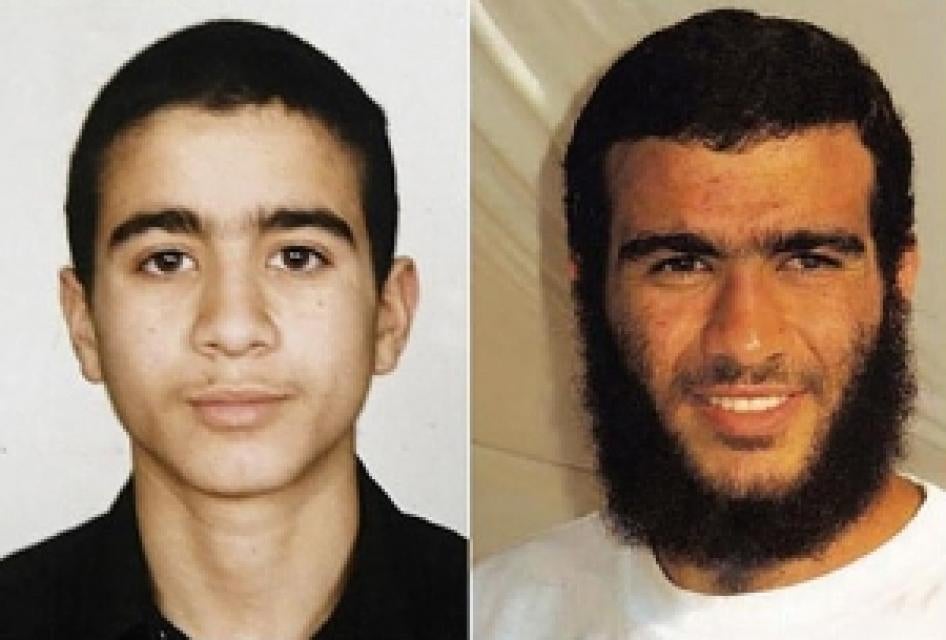

As I sat watching the sentencing hearing at Guantanamo Bay of Omar Khadr, a former child soldier, I wondered how his being detained here for eight years without trial could actually be used against him. But that was the thrust of the testimony on Tuesday before the military commission of the prosecution's expert witness on Khadr's future dangerousness. There Khadr sat, silently, hair and beard trimmed, in a dark suit, while over and over again, Dr. Michael Welner, a board certified forensic psychiatrist and creator of the "depravity scale," talked about how Khadr had been "marinating" in the radical jihadi views of elder statesmen of terrorist groups while at Guantanamo.

Khadr, only 15 at the time of his apprehension but 24 now, has pleaded guilty in a military commission to five charges, including murder in violation of the laws of war for the killing of US Army Sgt. First Class Christopher Speer. Speer was fatally wounded on July 27, 2002, after U.S. forces entered a compound in Afghanistan where Khadr and others were located. After a firefight ensued, prosecutors alleged Khadr threw a grenade that killed Speer and wounded others.

Khadr was also seriously wounded in the firefight, half-blinded in one eye and with two bullet wounds to his chest. In bringing the murder in violation of the laws of war charge before a military commission, the U.S. government is saying that the killing of a combatant openly on the battlefield is a war crime when committed by an irregular combatant. It's a novel legal argument: Merely engaging in battle as an insurgent rather than as a member of a regular army has never made such battlefield conduct a war crime. And Khadr's plea deal makes the U.S. the first Western nation since World War II to convict someone for acts committed as a child in a war crimes tribunal.

But none of this was heard by the military jury on Tuesday. Nor is there reason to believe it will be taken into account when the jury decides sentencing. While the public knows that Khadr, a Canadian national, has entered into a plea agreement, the military jury charged with sentencing has not been informed of the deal-eight years, one in Guantanamo followed by another seven in Canada. Instead, following courts-martial practice, they only know that Khadr has pleaded guilty and will issue a sentence after hearing testimony from both prosecution and defense witnesses. If by chance they issue a shorter sentence, Khadr gets the benefit. But if they issue a longer one, the terms of the plea agreement will govern.

It is hard to imagine the jury will issue a shorter sentence after seeing the direction the prosecution's case is taking. Dr. Welner appears to be their star witness, although he might be eclipsed by the widow of Sgt. Speer. Ms. Speer wept openly in court while the prosecution read a statement about how the grenade thrown during the firefight caused Speer mortal brain damage. She will testify later this week, as will former Army Special Forces Sgt. Layne Morris, who was blinded in one eye during the same firefight.

But on Tuesday, the focus of the testimony was on Khadr's remorse, or lack thereof. Two former interrogators testified that Khadr had bragged about killing a U.S. soldier and that he claimed the day he planted land mines to kill U.S. and coalition forces was the happiest day of his life. But neither had seen him since they last interrogated him in 2002, when he was 16 years old and still medicated from surgery for his near fatal injuries.

Former interrogators and Dr. Welner testified that when Khadr was angry at his guards, he would recall how he had killed a U.S. soldier and that would make him happy. The implication, of course, was that Khadr was, in the words of one interrogator, "cold and callous."

Unstated was why Khadr might be so angry at US soldiers as to relish in the death of one of them. The jury will never hear testimony about how Khadr was strung up like a big over the air vent to his cell in Bagram, or that interrogators told him a fictional story of a young man sent to an American prison who was gang-raped and died of related injuries-implying that Khadr might face a similar fate if he failed to cooperate.

They will never see the video of his interrogation by Canadian intelligence agents where he is lying on the floor crying for his mother. Nor will the prosecution present evidence of international law that required Khadr to be treated differently upon capture from other detainees because of his age.

Dr. Welner stated his conclusion at the outset: Omar Khadr is "highly dangerous." But the basis for his conclusion was far scarier than any threat of recidivism. He relied on Khadr's devoutness, the fact that while in Guantanamo he memorized the Koran (a respected feat in Islam) and has led prayer in his cell block. These factors apparently suggest that Khadr is a radical jihadi.

He acknowledged that Khadr has never been violent at Guantanamo and that the camp where he is housed is reserved for the most "compliant" detainees. But at the same time he insinuated that Khadr's fluency in several languages and ability to communicate with many different people was somehow negative. He seemed dismayed Khadr had not become more "Westernized" and fraternized more with his guards.

Further supposedly damning evidence was Khadr's charm. This, Dr. Welner suggested, would surely make Khadr an influential al Qaeda leader. The No. 1 reason that Khadr was dangerous: his father. A senior ranking al Qaeda leader now dead, Khadr's father took him to visit al Qaeda leaders when he was 10 and to a military training camp when he was 15. The fact that this constituted use and abuse by Khadr's father did not seem to be important. Dr. Welner apparently spent 500 to 600 hours working on Khadr's case for that conclusion, at a cost of several hundred thousand dollars to U.S. taxpayers.

The plea bargain indeed is a hand well played by the prosecution. It has cleansed this case of all its untidy aspects: the abuse allegations, the flouting of international law with respect to the treatment of juveniles, the invention of new war crimes and of an entirely new, untested, and deeply flawed legal process. None will be mentioned in the courtroom. Nor will the pathetic record of Guantanamo in general. Khadr's case is only the fifth to be prosecuted since Guantanamo opened its doors over eight years ago. This, despite the fact that more than 800 prisoners have passed through Guantanamo's gates, the vast majority of them entirely innocent. Of the 174 who remain, roughly half are due to be released. These statistics stand in sharp contrast to that of the tried, true, and more efficient U.S. federal courts, where more than 400 terrorism cases have been prosecuted since 9/11.

Instead, the prosecution parades a theory of dangerousness that has pervaded U.S. detention policy for years: The men in Guantanamo are dangerous, and they are dangerous because they are in Guantanamo.