(Dakar) - Tens of thousands of children at residential Quranic schools in Senegal are subjected to slavery-like conditions and severely abused, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Human Rights Watch urged the Senegalese authorities to regulate all Quranic schools and take immediate and concerted action to hold accountable teachers who violate Senegalese laws against forced begging and child abuse.

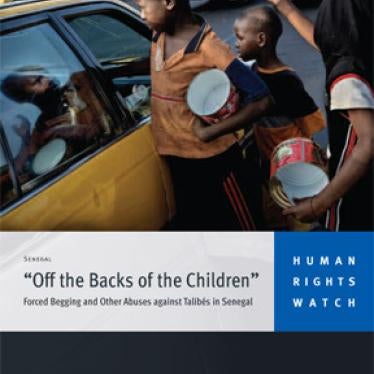

The 114-page report, "‘Off the Backs of the Children': Forced Begging and Other Abuses against Talibés in Senegal," documents the system of exploitation and abuse in which at least 50,000 boys known as talibés - the vast majority under age 12 and many as young as four - are forced to beg on Senegal's streets for long hours, seven days a week, by often brutally abusive teachers, known as marabouts. The report says that the boys often suffer extreme abuse, neglect, and exploitation by the teachers. It is based on interviews with 175 current and former talibés, as well as some 120 other people, including marabouts, families who sent their children to these schools, Islamic scholars, government officials, and humanitarian officials.

"Senegal should not stand by while tens of thousands of talibé children are subjected every day to beatings, gross neglect, and, in fact, conditions akin to slavery," said Georgette Gagnon, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. "The government should take the occasion of National Talibé Day, April 20, to commit to regulate all Quranic schools and hold abusive marabouts accountable."

In Senegal's predominantly Muslim society, where religious leaders wield immense social and political power, children have long been entrusted to marabouts who educate them in these residential Quranic schools, called daaras. Many marabouts, who serve as de facto guardians, conscientiously carry out the important tradition of providing young boys with a religious and moral education.

But research by Human Rights Watch shows that in many urban residential daaras today, other marabouts are using education as a cover for economic exploitation of the children in their charge. Many marabouts in urban daaras demand a daily quota from the children's begging and inflict severe physical and psychological abuse on those who fail to meet it. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases of beatings, and several cases in which children had been chained, bound, and forced into stress positions as they were beaten.

In the more than 100 daaras from which Human Rights Watch interviewed current or former talibés, the marabout typically collects between US$20,000 and $60,000 a year from the boys' begging - a substantial sum in a country where most people live on less than $2 a day. Interviews suggest that some marabouts amass upward of $100,000 a year through exploiting children in their care.

A Widespread Pattern of Abuse

An 11-year-old boy sent by his parents to a marabout in Dakar, Senegal's capital, at age seven told Human Rights Watch:

Every day I had to bring the marabout 600 CFA ($1.30), rice, and sugar. Every time I couldn't, the marabout would beat me with an electric cord. He would strike me so many times on the back and the neck; too many to count.... Each time I was beaten, I would think of my family, who never laid a hand on me. I would remember being at home. Eventually I ran away, I couldn't handle it anymore.

Human Rights Watch further documented the extremely precarious condition in which these boys live. The substantial sums of money, rice, and sugar collectively brought in by begging talibés are not used to feed, clothe, shelter, or otherwise provide for the children. Many of the children suffer severe malnutrition, while the long hours on the street put them at risk of harm from car accidents, physical and sexual abuse, and diseases.

A typical daara is an abandoned or partially constructed building that offers little protection from rain, heat, or cold. The children sleep as many as 30 to a small room. Disease spreads quickly and the children often fall ill - from skin diseases, malaria, and stomach parasites - but are rarely cared for by the marabouts. Instead, many children are forced to beg overtime to pay for their own medicines.

Most talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had only one change of clothes, and over 40 percent did not have a single pair of shoes, leaving them to beg barefoot. Some talibés said that when they saved up money from extra hours of begging and bought a new shirt or pair of pants, their marabout took the clothing and gave it to his own children.

"Instead of marabouts ensuring that the boys in their care have food, education, and proper shelter, all too often the young boys become the means to provide for the marabout and his family," Gagnon said. "This is unconscionable."

Exhausted by continuous abuse and near-total deprivation, more than 1,000 boys run away from daaras each year. Hundreds of children living on the streets in Senegal's major cities represent one of the defining legacies of the most exploitative residential Quranic schools.

A Catalog of Inaction

The Senegalese government enacted legislation in 2005 that criminalized forcing others into begging for personal financial gain. But the authorities have failed to take concrete steps to implement the law and end the exploitation and abuse of the talibés. Not one marabout has been charged or tried solely for the crime of forced begging, although large numbers of these children can be seen on the streets on any given day. In all but a few cases, severe physical abuse of the talibés has gone similarly unpunished.

With the exception of a few state-sponsored "modern" daaras - which combine Quranic and state school curricula - none of the Quranic schools in Senegal are subject to government regulation. This has in part led to the proliferation of unscrupulous marabouts who have little interest in educating or providing for children in their care.

Although many of the children in Senegal's daaras come from neighboring Guinea-Bissau, its government has failed to hold marabouts accountable even in clear cases of child trafficking. Guinea-Bissau also risks the practice of forced begging taking root domestically should it fail to learn the lessons of Senegal's decades of inaction.

Parents send their children to residential daaras largely out of a desire that they receive a religious education; many are also influenced by lack of financial means to support them at home. Most parents fail to provide any financial or emotional support when sending the child to a marabout. While some lack knowledge about the abuse - in part due to deliberate obfuscation by the marabout - others willingly send or return their children to a situation they know to be abusive.

Humanitarian aid agencies, trying nobly to fill the protection gap left by the government, sometimes find themselves caught up in the abuses. By focusing assistance on urban daaras and neglecting rural schools, many national and international humanitarian organizations provide the incentive to daaras to move from rural to urban areas, where forced begging is rampant. In some cases, the efforts of these organizations increase the profit margins of unscrupulous marabouts by giving aid directly to them and failing to monitor how the money is used. Such agencies often fail to report abuse or challenge state inaction, in part to maintain good relations with the marabout and the authorities.

"Millions of dollars are pouring in to humanitarian and government programs to help the talibés and prevent abuse, yet the prevalence of forced child begging in daaras continues to rise," Gagnon said. "The rampant abuse of these children will only be eradicated when the government brings offending marabouts to book."

The government's failure is a breach of its responsibilities under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, in addition to under conventions on trafficking, slavery-like conditions, and the worst forms of child labor.

Human Rights Watch also called on the Organisation of the Islamic Conference to denounce the practice of forced begging as contrary to human rights obligations under the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, and asked the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery to undertake an investigation into the situation of the talibés.