In his speech to parliament on the eve of the Iraq war, Tony Blair referred to "the brutality of the repression" of Saddam Hussein, "the death and torture camps, the barbaric prisons for political opponents, the routine beatings for anyone or their families suspected of disloyalty."

British forces did of course invade, occupy and govern part of Iraq and Saddam's torture chambers were shut down. But the evidence has grown that they were replaced with new forms of abuse of detainees, not only by the US but also by the British. With the UK forces now withdrawn, it is time to find out how this happened. The Chilcot inquiry is the place to do this.

The inquiry, with its wide remit, has made it clear that it will need to focus only on the key issues. As Human Rights Watch has underlined in a letter to the Chilcot inquiry this month, one of these issues must be British involvement in human rights abuses: not only because ending human rights violations in Iraq was used to justify the war, but because evidence has emerged that British abuses were systematic, not remedied and therefore could easily be repeated elsewhere.

The evidence that has emerged, gradually, over the years now indicates a record of widespread and serious abuses of Iraqis in British detention, including assaults, torture and several deaths. Some of these abuses have received considerable media attention and it is to be welcomed that one particularly notorious case, the beating to death of hotel receptionist Baha Mousa in September 2003, is now the subject of a belated public inquiry. But an inquiry into an individual case cannot get to the bottom of the apparently systematic nature of the abuse.

The recent publication by Public Interest Lawyers, the law firm involved in a number of individual cases, of the evidence that has been released to date, is a clear indication that abuse was not a matter of a few "bad apples" but appears to have been a common method of dealing with detainees.

Abuse in different forms continued up to the British departure. At the end of 2008, Britain handed over to the Iraqi authorities its final two detainees whom it had kept locked up for five years, claiming they were criminal suspects but without taking any steps to put them on trial. This handover occurred despite the serious risk to the men of their suffering an unfair trial and the death penalty in the Iraqi justice system, and despite a ruling from the European court of human rights that they should not be handed over.

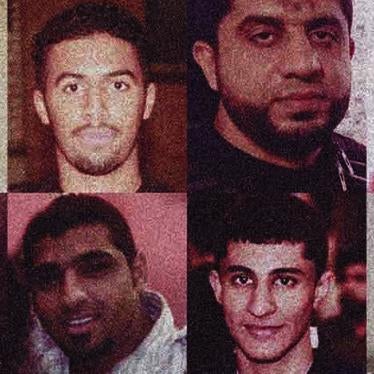

But is not only the abuse itself that needs to be addressed. What is equally striking is the lack of prosecutions once crimes were revealed. The response of the British authorities has been denial, excuse and cover-up. Even the broadcasting of a video in 2006, that appeared to show physical abuse of four detained children in a British camp two years earlier, led only to a statement by the army prosecutors that there was "insufficient" evidence for any prosecution.

The British government has taken one of the most extreme positions of any country in denying that any form of human rights law applies to its forces and officials outside Britain. It even denies that the international treaty against torture applies to its forces in Iraq, a more hardline position than the US. The result has been a high degree of lawlessness where British forces detained people for years on end.

There are four key areas in which an inquiry on the scale of Sir John Chilcot's is required to uncover what happened. First, how widespread were the abuses in detention? Only an inquiry that can question ministers and senior officers can find out at what level such abusive behaviour was authorised, including the apparent use of sensory deprivation that British governments made firm commitments to abandon 30 years ago, and what, if any, action was taken at the highest level to end such abuses when they came to light.

Second, the inquiry should investigate the failure to prosecute, despite the many cases of clear evidence of crimes, including the failure to trace responsibility up to those in authority. In fact, under international law, those in positions of authority should be held liable for the most serious crimes, such as torture, that they should have known about but failed to prevent or prosecute.

Third, the government should produce the basic rules it used to govern the use of detention by British forces in Iraq. Particularly important are the legal basis for detention, and ensuring independent review of all detention. After investigating the abuses in British detention the Chilcot inquiry would be able to recommend measures to ensure that these rules are improved so that risk of future abuse is minimised, abuses that are discovered are fully and publicly investigated and any crimes are prosecuted. There also need to be clear rules preventing the handing over of people to other governments where there is a risk of serious human rights abuses.

Fourth, the government's understanding of the applicable law needs to be investigated and challenged. It should be made clear that the international law the UK promotes so strongly, including human rights law, applies to British forces and officials, at the very least whenever and wherever they are in a position of authority.

By examining the serious abuses that took place in Britain's name after a war supposedly to bring basic human rights to the Iraqis, the Chilcot inquiry will be in a position to help ensure such abuses do not happen again.