House Majority Leader Barbara Smith

Warner

900 Court St. NE, Room H-295,

Salem, Oregon 97301

Senate President Peter Courtney

900 Court St. NE, Room S-201,

Salem, Oregon 97301

Dear Rep. Smith Warner and Sen. Courtney:

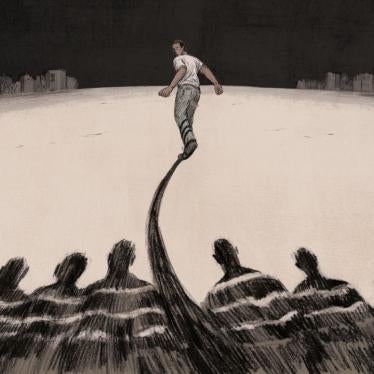

The undersigned national criminal justice reform and civil rights organizations are committed to expanding voting rights to all citizens including persons in prison. We write to applaud the introduction of HB 2366/SB 571, which would end felony disenfranchisement and facilitate full political and civic participation for thousands of Oregonians. We urge the Oregon Legislature to pass HB 2366/SB 571. Oregon currently disenfranchises individuals serving a felony sentence of incarceration. As of March 2021, as many as 12,548 —are disenfranchised.[1]

Oregonians want the state’s suppressive felony disenfranchisement practice to end. If HB 2366/SB 571 is adopted, Oregon will join the ranks of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia as jurisdictions that proudly impose no voting restrictions on individuals with felony convictions, thereby permitting citizens to assume civic responsibilities during their incarceration. As Anthony Richardson, an Oregonian imprisoned on a life sentence says, “Oregon can lead the way. By restoring voting rights, we strengthen our democracy and create a more equitable, inclusive and fair Oregon.”[2]

The passage of HB 2366/SB 571 would serve as a model for the remaining 47 states. The time is right for the state to advance this reform—to expand the electorate and strengthen democracy in order to represent all individuals and all communities in Oregon.

Ending Felony Disenfranchisement Would Serve Reentry and Public Safety

While there is no legitimate justification for felony disenfranchisement, there is ample reason to believe that providing the right to vote would benefit Oregon. Enfranchising people convicted of crimes is also a vital step toward ensuring the safety of Oregon’s communities. Research shows that “[formerly incarcerated persons] who enter stable work and family relationships are most likely to desist from crime.”[3] This is because once an individual with a criminal record rejoins the community—through gainful employment, payment of taxes, and resumption of family duties—he or she becomes accountable to the other members of that community. Any and all duties that help him or her fully reintegrate will motivate that individual to further engage in community-based activity and away from criminality. Assuming responsibilities of a “voting member of one’s community would appear to be a logical analog to work and family reintegration.”[4]

Felony Disenfranchisement Perpetuates A Legacy of Racism

Felony disenfranchisement laws in the United States have troubling race and class dimensions that cannot be reconciled with our shared present-day values of equal citizenship and equal dignity.

Scholar Ward Elliott has observed that the spread of disenfranchisement laws may have been a response to the abolition of property-holding requirements. After Reconstruction, states in the South began to tailor their disenfranchisement laws to cover crimes for which Black citizens were most frequently prosecuted, “as part of a larger effort to disenfranchise African American voters and to restore the Democratic Party to political dominance.”[5] Over time, states stopped distinguishing between kinds of crimes, instead imposing blanket disenfranchisement for all felony convictions.

Although the country has changed and states have repudiated discriminatory barriers to voting such as poll taxes and literacy tests, felony disenfranchisement laws have persisted. And they continue to have a disproportionate racial impact due to the pervasive racial bias in the criminal justice system.

Black and Latinx residents make up 32% of the U.S. population, but in 2015 they comprised 56% of all incarcerated persons in the country.[6] This is because individuals of color are prosecuted and sentenced at much higher rates than whites for comparable behavior. For example, in a national survey on drug use, it was reported that “African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost 6 times that of whites.”[7] African Americans “represent 12.5% of illicit drug users, but 29% of those arrested for drug offenses and 33% of those incarcerated in state facilities for drug offenses.”[8]

Troublingly, the prison population has been rising in Oregon far faster than population growth. In 1980, the prison population was 3,125.[9] Today, the state imprisons 12,548 people, a growth of nearly 378%. While nationally the prison population dropped 9% from 2009 to 2018, it rose 1% in Oregon over that same period[10] although the state has experienced declines since 2020.

Oregon Can Lead the Way

Two states in America—Maine and Vermont— as well as Puerto Rico and Washington DC do not disenfranchise their citizens for felonies. Maine and Vermont typically boast voter turnout higher than the national average, with Maine often taking the top spot nationally. Now other states are beginning to recognize the importance of restoring the right to vote. Since 1997, 25 states have expanded voting rights to citizens with felony convictions.

Oregon can build off that momentum and take it one step further by restoring the right to vote for those still serving prison sentences. Four other states have introduced legislation to end felony disenfranchisement this year: Maryland (HB 53) Massachusetts (SD 2049, HD 3701), New Mexico (HB 74) and Virginia (HJ 555, SJ 272). In this democratizing moment, the state that acts first will instantly become a leader on democracy and set an example of inclusion for the rest of the country. We urge Oregon to seize its moment of opportunity with HB 2366/ SB 571.

If you have any questions or would like to discuss this further, please contact Nicole D. Porter, Director of Advocacy at The Sentencing Project, at 202-628-0871 or nporter@sentencingproject.org.

Sincerely,

Advancement Project

A Little Piece Of Light

Chicago Votes Action Fund

Civil Survival Project

Coalition of Effective Public Safety

Common Cause and Common Cause Oregon

CURE (Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants) and Oregon CURE Gamiel Network

Health in Justice Action Lab

Higher Dimensions Inc.

Human Rights Watch

Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy

Interfaith Action for Human Rights

Just Futures Law

Legal Action Center/National H.I.R.E. Network

National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

National Association of Social Workers

Nebraskans for Prison Reform

Mommieactivist and Sons

Quaker Voice on Washington Public Policy

Project on Addressing Prison Rape

Release Aging People in Prison

StoptheDrugWar.org

The Center for Community Transitions

The Daniel Initiative

The Sentencing Project

Students for Sensible Drug Policy

Washington Statewide Reentry Council

[1] Oregon is among 19 states that deny voting rights to all persons convicted of a felony who are in prison. Twenty-nine states deny voting rights to people with varying types of convictions both in prisons and in the community. See Felony Disenfranchisement: A Primer (The Sentencing Project, Washington DC). This total is calculated from the current number imprisoned in DOC is 12,404 (Oregon Dept of Corrections: Inmate Population Profile for 03/01/2021). While youth in custody can generally vote, those convicted as adults are disenfranchised, even if they are in Oregon Youth Authority (OYA) custody; that overall number is 151 with 144 of those youths being over 18 (QuickFacts.pdf (oregon.gov)).

[2] Oregon Justice Resource Center “Video: Voting is a Civil Right” (2020). Available at: https://twitter.com/OJRCenter/status/1364243627678064641?s=20

[3] Cristopher Uggen & Jeff Manza, Voting and Subsequent Crime and Arrest: Evidence from a Community Sample, 36 COLUM. HUM. RTS. L. REV. 193, 197 (2004-2005) (citing Robert Sampson & John Laub, Crime and Deviance over the Life Course: The Salience of Adult Social Bonds, 55 AM. SOC. REV. 609, 617-618 (1990); Cristopher Uggen, Work as a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment, and Recidivism, 65 AM. SOC. REV. 529, 542 (2000)); John Laub et al., Trajectories of Change in Criminal Offending: Good Marriages and the Desistance Process, 63 AM. SOC. REV. 225, 237 (1998).

[4] Uggen & Manza, supra note 15, at 197.

[5] Pippa Holloway, “A Chicken-Stealer Shall Lose His Vote”: Disenfranchisement for Larceny in the South, 1874-1890, 75 J. S. HIST. 931, 931 (2009); see also Hamilton-Smith & Vogel, supra note 19, at 409 (“Disenfranchisement became an important aspect of the Jim Crow laws used in reconstruction-era America to continue to subjugate the newly-freed slaves.”).

[6] NAACP, Criminal Justice Fact Sheet, available at https://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/ (emphasis added).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.