5 March 2021

Igor Viktorovich Krasnov

Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation

Prosecutor General’s Office

ul. B.Dmitrovka, d.15a 125993

Moscow GSP- 3 Russian Federation

Dear Prosecutor General,

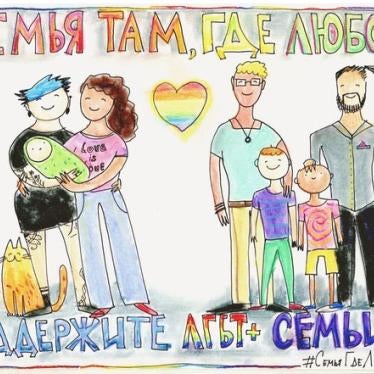

We are writing to express our concern and request your action regarding the unfounded criminal prosecution of Yulia Tsvetkova, women’s and LGBT rights activist, theater worker and artist from Komsomolsk-on-Amur. She is facing from two to six years in prison on “pornography” charges for sharing body-positive artwork about female anatomy on social media.

On February 8, 2021, the deputy prosecutor of Khabarovsk region, M. Sobchuck approved the indictment against Yulia Tsvetkova on charges of “illegal production and distribution of pornographic materials” (Article 242 (3) (b) of the Criminal Code). To prevent a miscarriage of justice, we request that you look into the case with a view to using your mandate to withdraw the indictment and drop all charges against Ms. Tsvetkova.

The charges sprang from Ms. Tsvetkova’s activities as the administrator for Vagina Monologues, a public group on vk.com. According to the group’s self-description on its VKontakte page, it is intended for women, dedicated to combating stigmatization of female physiology and includes artwork and articles about “the beauty, power and uniqueness of female anatomy.” [1] The group’s vk.com page provides a disclaimer that it might contain images not intended for persons younger than 18.

We believe that it is self-evident that Ms. Tsvetkova’s activities that underlie the charges do not meet the definition of the offence set out in Russian law, and as such the charges lack a proper legal basis. According to the Constitutional Court ruling from January 29, 2009, article 242 of the Criminal Code requires direct intention as the mens rea for criminal liability in cases relating to pornography production and distribution.[2] Article 242 does not include a legal definition of what constitutes “pornographic materials.”

While article 2(8) of the Law on Protection of Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development does provide a definition of “information of pornographic character”,[3] this definition is relevant only in the context of that law. The Constitutional Court has explicitly stipulated that that law does not contain the same definition as the “pornographic materials” term in the Criminal Code.[4]

Russian courts, in the context of the dissemination of “pornographic materials”, have already distinguished materials which have the primary intent of stimulation of sexual arousal, from those whose purpose is “drawing attention to natural physical beauty.”[5]

Indeed, the Criminal Code itself distinguishes between pornographic images and artistic images of reproductive organs. This can be seen in article 242.1 which prohibits “producing and distributing pornographic materials with children’s images,” and provides that images of reproductive organs do not constitute pornographic materials if they have an artistic value. We raise this to illustrate the distinction recognized in law between different materials, as Ms. Tsvetkova is not charged under Article 242.1, and her public page on vk.com does not contain any images of children.

It should therefore be self-evident that artwork depicting female anatomy with a clearly outlined goal of celebrating the beauty of female anatomy, is not and should not be considered pornographic under Russian law. To treat such material as pornographic would, at the very least, be an unforeseeable application of the law, and therefore violate a fundamental requirement that laws, in particular criminal laws, are foreseeable and accessible. This principle of legality means that provisions in criminal law must be clear enough so that “an individual can know from the wording of the relevant provision and, if need be, with the assistance of the courts' interpretation of it, what acts and omissions will make him criminally liable”.[6]

The prosecution is also a violation of the right to freedom of expression, which includes artistic expression, as protected under international law and explicitly under treaties to which Russia is a party. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (article 19) provides that everyone has the right to freedom of expression and freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds in the form of art, and similar protections are provided under the European Convention on Human Rights (article 10) as articulated in multiple judgments of the European Court of Human Rights.[7] The Court is clear that artistic expression is protected, even if it offends, shocks or disturbs, some people.

The prosecution also unjustifiably interferes with the right to take part in cultural life protected by article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which Russia has also ratified. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has emphasized that this right is intrinsically linked to rights “such as the rights to privacy, to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, to freedom of opinion and expression, to peaceful assembly and to freedom of association”. In all cases limitations of these rights must be necessary and proportionate, and established by legal rules that are transparent and consistently applied in a non-discriminatory way. [8]

Tsvetkova’s prosecution is not necessary let along proportionate (the penalty is a minimum of two years deprivation of liberty) and is not based on a clear and foreseeable application of the law. Indeed, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that charges have been brought against her in retaliation for her peaceful and legitimate activism.

Whether or not this unfounded prosecution continues it should be noted that the prolonged investigation has in and of itself already caused serious harm to Ms. Tsvetkova’s enjoyment of her fundamental rights. The investigation has lasted 15 months, during which time her movements were restricted, and her work affected. On November 20, 2019, police required her to sign an undertaking not to leave her home city. Three days later, Central District Court placed her under house arrest, which was lifted only on March 16, 2020. Since October 2019 the investigative committee has attempted to indict Tsvetkova four times. The prosecution returned three of these indictments for further investigation. Meanwhile, the investigation on “pornography” charges prevented Tsvetkova from continuing her legitimate work as a women’s and LGBT rights activist.

We call on you to take all necessary steps to address the unfounded investigation against Yulia Tsvetkova and to drop the charges and halt this unfounded prosecution.

Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia Director, Human Rights Watch

Svetlana Zakharova, Director, Charitable Foundation “Sphere”

Geir Hønneland, Secretary General, Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Aleksandr Cherkasov, Board Chair, Human Rights Center Memorial

Denis Krivosheev, Deputy Director for Research, Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regional Office, Amnesty International

Ana Furtuna, Director of Eurasia Department, Civil Rights Defenders

Dr Srirak Plipat, Executive Director, Freemuse

[1] Монологи Вагины. Может содержать материалы 18+. [Vagina’s Monologues. Might contain images not intended for children younger than 18 y/o.], accessed March 1, 2021, https://vk.com/vagina_monologues

[2] On refusal to accept for consideration the complaint of a citizen Kaptsugovich Sevastian Igorevich on violation of his constitutional rights under Article 242 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, Constitutional Court of Russia, Case No. 41-О-О, Ruling, January 29, 2009, para. 2.

[3] Federal Law on Protection of Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development, Russian newspaper, No. 436-FZ, December 29, 2010, art. 2.

[4] On refusal to accept for consideration the complaint of a citizen Korolyov Dmitry Ivanovich on violation of his constitutional rights under Article 242 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, Constitutional Court of Russia, Case No. 1746-О, Ruling, July 19, 2016, para. 2.

[5] Shestalo S., “Вопрос: Что понимается под порнографическими материалами и какая ответственность предусмотрена за изготовление и распространение порнографических материалов или предметов?” [“Question: What is understood under pornographic materials and what are the sanctions for producing and disseminating pornographic materials or objects?”], SPS KonsultantPlius, February 10, 2021.

[6] Cantoni v. Switzerland, application no. 17862/9, Grand Chamber of ECtHR judgement November 15 of 1996, §29; Huhtamaki v. Finland, application no. 54468/09,ECtHR judgement of March 6 of 2012, paragraph 44.

[7] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 993 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force January 3, 1976 and European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 213 U.N.T.S. 222, entered into force September 3, 1953, as amended by Protocols Nos 3, 5, 8, and 11 which entered into force on September 21, 1970, December 20, 1971, January 1, 1990, and November 1, 1998, respectively.

[8] UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 21, Right of everyone to take part in cultural life, U.N. Doc. E/C.12/GC/21 (2009), para. 19.