‘This is a historic day.’

The words sent a shiver down my spine, as applause erupted at the United Nations in Geneva on June 21st. The governments, worker representatives and employer organisations which make up the International Labour Organization (ILO) had just voted for a new treaty tackling the scourge of violence and harassment at work.

For over 10 years, I have interviewed hundreds of domestic workers—in the Middle East, Asia and east Africa—who told me about physical, psychological and sexual abuse at the hands of their employers. These are women such as Jamila A (the name changed for her security), a Tanzanian domestic worker previously employed in Oman, who told me that the men in the household would hide her bedroom key so she was forced to sleep with the door unlocked. ‘All of the men, even the old man, harassed me,’ she said.

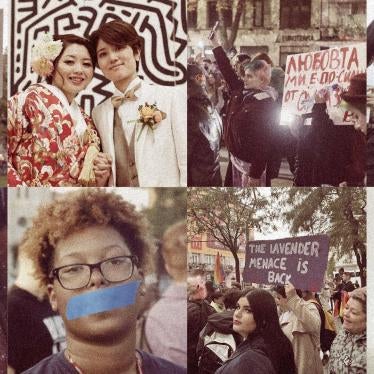

In 2017, the #MeToo movement erupted and spread around the world with women, and some men, breaking the silence to speak out about the abuse they faced at work or from people who had huge sway over their careers. This movement built on decades of awareness-raising by women’s and workers’ organisations and coincided with the discussions already under way at the ILO.

The ugly reality is that abuse is endemic in many workplaces—with victims in sectors ranging from the most powerful to the most marginalised. But harassment and violence at work are often shrugged off in public discourse, as an inevitable ‘fact of life’ that has existed for generations.

Clearly Defined Steps

The new ILO Convention on Violence and Harassment refutes that notion by reinforcing and elaborating the right to freedom from violence and harassment in the world of work. It provides governments and employers with clearly defined steps to protect this right and to ensure that we can all work in safety and dignity.

Governments which become party to the treaty will agree to meet legally binding standards. The experience of past ILO treaties, and other human rights instruments, shows that those standards over time tend to become the international norm. So even governments which do not join the treaty will move closer to those standards to stay in step with their neighbours.

What does the treaty do?

First, it requires countries to prohibit violence and harassment at work in their laws and policies. They have to work to prevent it, to investigate violence that does occur and to provide remedies and protection from retaliation for victims. Officials should take an integrated and gender-responsive approach, through provisions in labour law, occupational-safety and health law, anti-discrimination or equality laws and criminal law, where appropriate. They should also require employers to have workplace policies addressing violence and harassment, with risk assessments, prevention measures and training.

Secondly, the treaty is progressive in that it covers not only current employees but also applicants, job-seekers, trainees, interns and volunteers. These are often some of the most vulnerable groups, due to their lack of power or their position on the weaker side of a clear power imbalance.

Take Harvey Weinstein, for example. Several women who had not even applied for specific jobs described numerous occasions when they said he insisted on sexual favours or acts in return for opportunities in the film industry or even threatened them with denial of such opportunities if they didn’t comply.

Governments should also address third parties who harass or are harassed. For instance, in 2017 Chicago City Council passed an ordinance requiring hotel employers to provide a panic button or notification device to workers assigned to clean or restock guest rooms or restrooms alone. This allows them to call for help if the employee ‘reasonably believes that an ongoing crime, sexual harassment, sexual assault or other emergency is occurring in the employee’s presence’.

Beyond the Four Walls

Thirdly, in another groundbreaking aspect, the treaty recognises that the world of work extends far beyond the four walls of an office or factory and includes work-related travel, daily commutes and work-related social events. For example, employers can work with unions and workers to help prevent harassment, such as by providing street lighting near the workplace or transport home late at night.

The client dinner is another classic example. The employer can argue they have no control of a social event outside the office or of a client who is not their employee. But employers do have some options. If the employer presses the worker to maintain the relationship, despite harassment, they are putting her at risk of further harm. A workplace policy can create channels for workers to report harassment, and to outline how employers should respond.

Fourthly, the treaty requires governments to adopt legal protections on equality and non-discrimination at work. Women, migrants, LGBTI people, and members of ethnic minorities are among those who face a greater risk of violence and harassment at work, due to perceived differences and power inequalities. Discrimination is at the root of such violence.

Fifthly, domestic violence follows its victims to their workplaces and governments should take measures to mitigate the impact. An increasing number of governments have adopted laws to prohibit employers from dismissing victims of domestic violence, for simply being victims, or have introduced specific leave provisions.

In 2018, New Zealand became the most recent country to pass such legislation–granting victims of domestic violence 10 days of paid leave to leave their partners, find new homes and protect themselves and their children. These measures can save lives.

Overwhelming Majority

The ILO convention was adopted by an overwhelming majority: not a single government voted against it and only a handful abstained. It is accompanied by a recommendation which provides further guidance on the obligations it sets out.

Jamila A and many of the other women I spoke to over the years shared their stories with the hope that no other woman would suffer what they endured.

Countries should start to take steps to ratify the convention, develop action plans and begin to make those hopes a reality.