(Moscow) – A well-known Tajik athlete faces possible torture or ill-treatment if he is forcibly returned from Belarus to Tajikistan, the Association for Central Asian Migrants, Human Rights Watch, and Norwegian Helsinki Committee said today. Belarus should not extradite or deport the athlete, Parviz Tursunov, or otherwise facilitate his forced return.

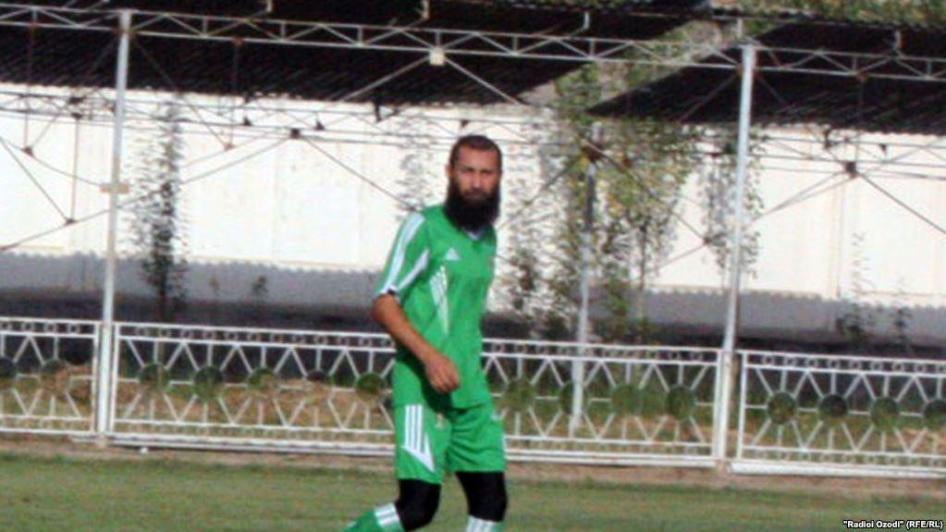

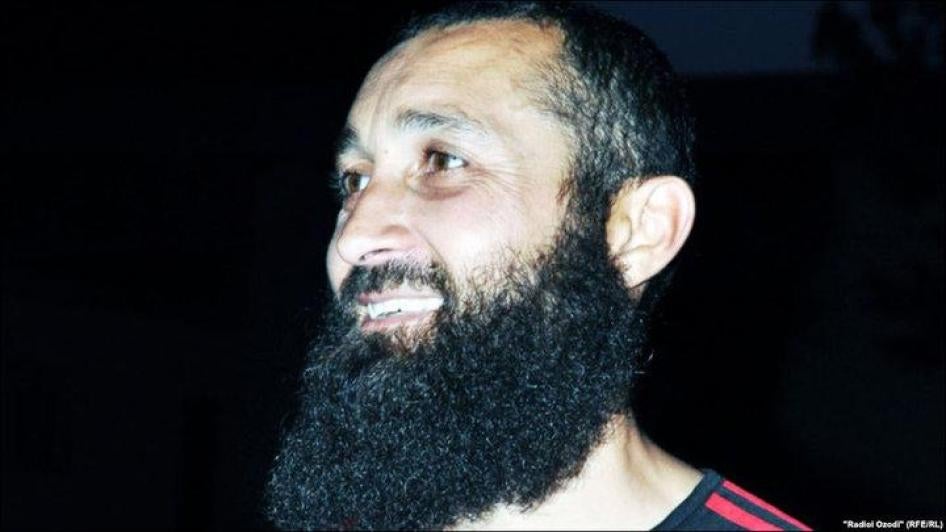

Belarusian migration police at Minsk International Airport detained Tursunov, a former professional soccer player in his country’s premier soccer league, under a Tajik extradition request on September 18, 2018, after he landed in Minsk. Tajik authorities had demanded that Tursunov shave his beard, which he wears as a manifestation of his religious belief. When he refused, in 2011, the Khayr team dismissed him.

“Tajikistan’s long-running and severe crackdown on religious believers is taking increasingly absurd forms, such as labeling a person an extremist simply for wearing a beard,” said Steve Swerdlow, Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Belarus has a legal obligation not to send Tursunov to anywhere he could face torture or ill-treatment, such as Tajikistan, and it should abide by those international commitments.”

Over the past decade, Tajikistan has imposed a de facto ban on men wearing beards and women wearing the hijab as part of a wide-ranging crackdown on independent Muslims, who practice Islam outside strict state controls. By labeling Tursunov an adherent of “extremist” Salafi Islam for wearing a beard, authorities have brought politically motivated charges of “mass calls to extremist activity” against him for the peaceful exercise of his religion.

Tajikistan intensified its severe, widespread crackdown on free expression and association, peaceful political opposition activity, the independent legal profession, and the independent exercise of religious faith in 2018. Well over 150 political activists, including a number of lawyers, remain unjustly jailed. Relatives of dissidents who peacefully criticize the government from outside the country have been subjected to retaliation, such as arbitrary detention, threats of rape, confiscation of passports and property, and vigilante justice at the hands of sometimes violent mobs.

Tajikistan severely restricts religious freedom, regulating religious worship, dress, and education, and imprisons numerous people on vague charges of religious extremism. Authorities also suppress unregistered Muslim education throughout the country, control the content of sermons, and have closed many unregistered mosques. Under the pretext of combating extremist threats, Tajikistan bans several peaceful minority Muslim groups.

Tursunov, 43, was a defender for the Khayr soccer team and popular in the team’s native city of Vahdat. The Tajik media outlet “Asia-Plus” reported in April 2011 that Khayr’s head coach, Tohir Muminov, had stated that Tursunov would be excluded from playing in games because “law enforcement bodies do not wish to see a soccer player on the field wearing a long beard, like a mullah.” Tursunov responded by saying that were he to be forced to choose between his beard and the sport, he would choose the former, citing the importance of his religious faith. The team ousted him the next day.

Tursunov and his family later left for the United Arab Emirates, and then Turkey, where they worked as migrant workers, cooking and selling Tajik traditional cuisine. In September 2018, the family decided to travel to Europe via Belarus.

Tursunov’s relatives told the rights groups that since his detention on September 18, Tursunov has been held in Minsk’s pre-trial detention center no. 1 pending possible extradition to Tajikistan. The Belarus Prosecutor-General confirmed that it is awaiting documentation on the extradition request and that Tajik authorities have charged Tursunov with “public calls for carrying out extremist activity” (art. 307(1)(2)) and “organizing an extremist community” (art. 307(2)(1)) of Tajikistan’s criminal code. Authorities routinely invoke article 307 charges in politically motivated cases.

Despite reforms to Tajikistan’s criminal code that outlaw torture, as defined under international standards, torture is an enduring problem in Tajikistan. Police and investigators often use it to coerce confessions, and human rights groups have received many credible reports of torture of people associated with political opposition groups. The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly held that there is a serious risk that a person forcibly returned to face charges in Tajikistan would be tortured or subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment. The court also rejected as unreliable assurances from the Tajik government that it would not subject anyone sent back to prohibited treatment.

As a matter of international law, and specifically as a party to the Convention against Torture, Belarus is obliged to ensure that it does not forcibly send anyone to a place where they face a real risk of torture, or other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Although Belarus is not a member of the Council of Europe, a decision to flout the prohibition on return to torture or inhuman treatment would damage its relationship with the council and future membership plans.

“Opposition members, lawyers, journalists, and human right activists have long been in the crosshairs of the Tajik government,” said Marius Fossum, regional representative of the Norwegian Helsinki Committee in Central Asia. “That authorities are also targeting athletes for wearing beards shows even more clearly how cruel and absurd the crackdown has become.”