Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 2018

Remarks of Sarah Leah Whitson, Executive Director, Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa Division

Ethnic, religious, sectarian, tribal, and gender-based discrimination and hatred are nothing new in the Middle East, but sadly we’ve seen what appears to be a violent and destructive escalation of these trends throughout the region, which have ripped apart entire countries, such as Iraq and Syria. We now see national political strategies – which in reality are about competition among rival states for power and control over the region – sold to citizenry based on sectarian hatred, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. We also know that the control for politics and power can take on intra-sectarian divisions, such as political, democratic Islamists vs monarchical, unelected Islamists; or nominally secular states against Islamists, etc.

We’ve seen a great deal of coverage of religious discrimination within countries against particular religious minorities, such as Christians in Egypt or Iraq, or even the Sunni minority in Iraq. There is a tragic trend towards de-diversification throughout the region.

But perhaps the least attention has been paid to the fate of Shia minorities in Sunni dominant countries. We have, over the years, documented instances of hate speech in Egypt against the very small Shia population in the country, as well as deliberate attacks on Shia shrines by armed groups in Syria, where the conflict has entirely become characterized as a Shia/Sunni split instead of a non-sectarian struggle against an authoritarian government. We’ve also documented the targeting and persecution of the Shia majority population – ruled by a Sunni minority royal family – in Bahrain, represented by the harassment and jailing of Shia clerics who have voiced opposition to the government.

Today I’ve been asked to comment on an issue we have investigated more thoroughly, and that is Saudi Arabia’s discrimination against its Shia minority population, who are about 10-15% of the total, predominantly based in the country’s Eastern Province. For decades, Shia grievances have erupted into demonstrations and protests, and almost always have been met with violence from the state, and arrests – and execution of –Shia clerics. In 2016, Saudi Arabia executed the most prominent Shia cleric and leader, Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, after a Saudi court convicted him on a host of vague charges apparently based largely on his peaceful criticism of Saudi officials.

We first documented the institutional discrimination against the country’s Shia population in 2009, and there is no evidence to suggest that the situation has improved. Saudi Arabia systemically discriminates against its Shia community in public education, the justice system, religious freedom, and employment.

The government does not allow any public places of worship for non-Sunni communities, most significantly Shia mosques; authorities regularly shut down even private Shia halls for communal prayer.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia has historically excluded Saudi Shia from serving in certain public-sector jobs and high political office. There are currently no senior Shia diplomats or high-ranking military officers. Shia students generally cannot gain admission to military or security academies or find jobs within the security forces. In 2014, then-king Abdullah appointed the first-ever Shia cabinet member, an Ismaili named Mohammed Abu Saq, who serves as minister of Shura Council affairs. Saudi Arabia has only ever appointed one Shia ambassador, Jamil al-Jishi, who served as Saudi ambassador to Iran between 1999-2003. No Shia woman has ever held a high-level political position.

Anti-Shia bias has also presented itself within the criminal justice system, which is entirely staffed by Sunni religious scholars. As of April 2017, Human Rights Watch does not know of any Shia citizens who have served as prosecutors or judges in criminal courts. Shia to whom Human Rights Watch spoke almost universally alleged that false claims against Shia based on religiously motivated charges, such as cursing God, the Prophet, or his companions, are a staple of discriminatory acts against Shia. In 2014, one Saudi Shia man claimed that the personal status court in Dammam had refused to hear his testimony because he was Shia. In 2015, a Saudi court sentenced a Shia citizen to two months in jail and 60 lashes for hosting private Shia group prayers in his father’s home. In 2014, a Saudi Arabia court convicted a leading Saudi Sunni activist for religious tolerance, Mikhlif al-Shammari, of the supposed crime of “sitting with Shia.” Sunni judges sometimes disqualify Shia witnesses based on their religion. Since 1980, Saudi Arabia has officially permitted two courts in the Eastern Province to settle personal status, endowments, and inheritance issues for Saudi Shia according to the Shia Jaafari school of jurisprudence.

Yet the most troubling aspect of discrimination against Shia, because of the extent to which it also propagates hatred and discrimination against Shia among the Sunni population at large, is the government’s official hate speech.

Despite its official narrative of reform and inter-faith harmony (outside the country), our most recent research found that Saudi Arabia permits various Saudi state clerics and institutions to incite hatred and discrimination against religious minorities. The government has allowed government-appointed religious scholars and clerics to refer to religious minorities, such as Jews, Christians and Sufi Muslims, in derogatory terms or demonize them in official documents and religious rulings that influence government decision-making.

Government clerics, all of whom are Sunni, often refer to Shia as rafidha or rawafidh (rejectionists) and stigmatize their beliefs and practices. They have also condemned mixing and intermarriage. One member of Saudi Arabia’s Council of Senior Religious Scholars, the country’s highest religious body, responded in a public meeting to a question about Shia Muslims by stating that “they are not our brothers ... rather they are the brothers of Satan…”.

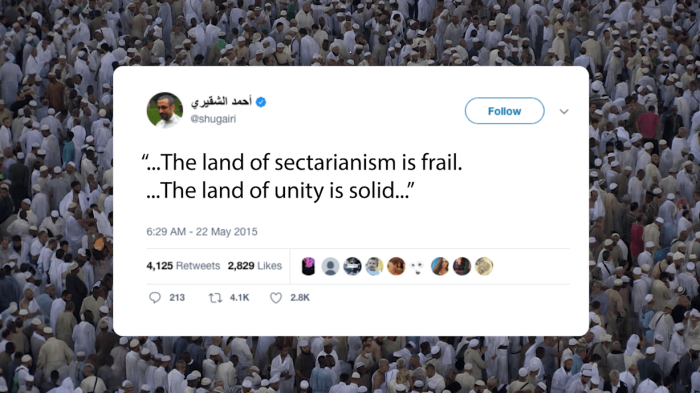

The hateful language is very much part of the government’s official statements. Saudi Arabia’s former grand mufti, Abdulaziz Bin Baz, who died in 1999, condemned Shia in numerous religious rulings. Bin Baz’s body of fatwas and writings remain publicly available on the website of Saudi Arabia’s Permanent Committee for Islamic Research and Issuing Fatwas. Some clerics use language that suggests Shia are part of a conspiracy against the state, a domestic fifth column for Iran, and disloyal by nature. The government also allows other clerics with enormous social media followings – some in the millions – and media outlets to stigmatize Shia with impunity.

The discrimination is most evident in the Saudi educational system’s religious curriculum, which contains hateful and incendiary language toward religions and Islamic traditions that do not adhere to its interpretation of Sunni Islam. Our comprehensive review of the Education Ministry-produced school religion books for the 2016-17 school year found that some of the content that first provoked widespread controversy for violent and intolerant teachings in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks remains in the texts today, despite Saudi officials’ repeated promises to eliminate the intolerant language. The texts disparage Sufi religious practices and label Jews and Christians “unbelievers” with whom Muslims should not associate. But we found this hateful language used most dramatically against the country’s Shia Muslim minority, using veiled language to stigmatize Shia religious practices. Saudi religious education textbooks denigrate the Shia practice of visiting graves and religious shrines and deem them as grounds for removal from Islam, punishable by being sent to hell for eternity.

Here’s a short video to give you some examples of what this looks like:

The government-sanctioned hate speech prolongs the systematic discrimination against the Shia minority and – at its worst – is employed by violent groups who attack them. Armed groups such as the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, or Al-Qaeda have used it to justify targeting Shia civilians. Since mid-2015, ISIS has attacked six Shia mosques and religious buildings in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province and Najran, killing more than 40 people. ISIS news releases claiming these attacks stated that the attackers were targeting “edifices of shirk,” (polytheism), and rafidha, (rejectionist), terms used in Saudi religious education textbooks to target Shia.

Saudi Arabia has faced pressure to reform its school religion curriculum since the September 11 attacks, particularly from the United States, after it was revealed that 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi citizens. The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has since 2004 classified Saudi Arabia as a “country of particular concern” under the International Religious Freedom Act – its harshest designation for countries that violate religious freedom. The designation should trigger penalties, including economic sanctions, arms embargoes, and travel and visa restrictions. But, while intolerant language remains in the school textbooks today, the US government has issued waivers on penalties since 2006.

In February 2017, Saudi’s education minister admitted that a “broader curriculum overhaul” was still necessary, but did not offer a target date for when this overhaul should be completed. Instead, in an interview during his recent U.S. tour, Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman feigned ignorance of anti-Shia discrimination, instead describing Saudi Arabia as a country of Sunnis and Shias. “As I told you, the Shiites are living normally in Saudi Arabia. We have no problem with the Shiites.”

In light of these repeated broken promises for reform, the US government should rescind the waiver and work with Saudi authorities to end incitement to hatred and discrimination against Shia and Sufi citizens, as well as adherents of other religions. The US should also press for removal of all criticism and stigmatization of Shia and Sufi religious practices, as well as practices of other religions, from the Saudi religion education curriculum. Members of Congress also should support the Saudi Educational Transparency and Reform Act because it will show Saudi authorities that the United States will not settle for half-measures on textbook reforms. The bill provides a unique opportunity to demonstrate whether Bin Salman’s policy changes will benefit all of Saudi Arabia’s citizens, including religious minorities, through removing hate speech once and for all from the country’s religion curriculum.