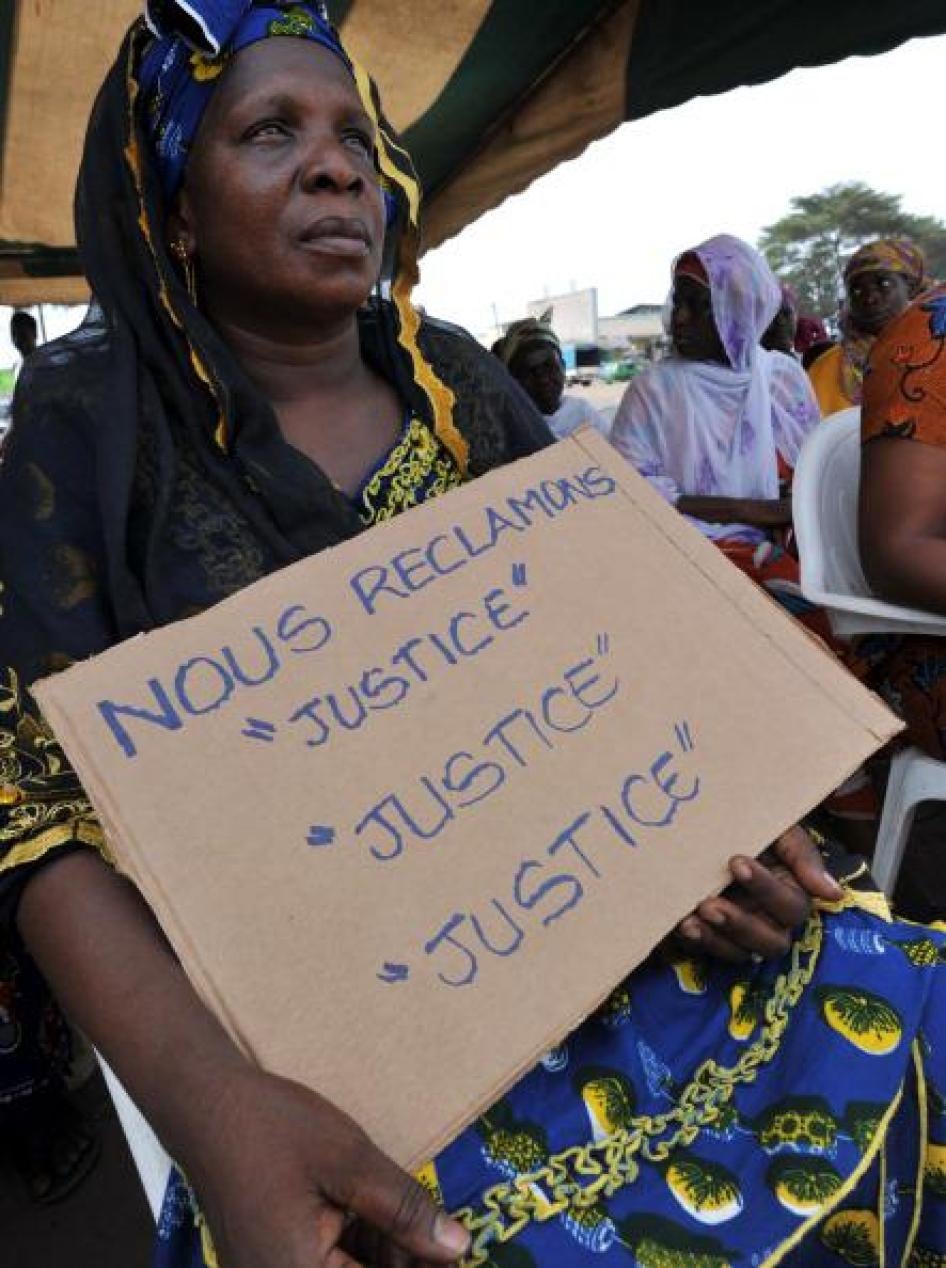

Since the turn of the year, there has been a flurry of activity in Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system. Ivorian courts have convicted more than ten allies of former president Laurent Gbagbo for crimes committed in the aftermath of the 2010-11 post-election crisis, including a June 2012 cross-border attack that killed seven UN peacekeepers. Victims of the rape, torture and extrajudicial killings committed during the post-election crisis itself, however, are still waiting for justice.

The 2010-2011 post-election crisis began when Gbagbo refused to cede power to Alassane Ouattara following the November 2010 presidential elections. In the resulting five months of violence and armed conflict, at least 3,000 people were killed and more than 150 women raped, with armed forces on both sides targeting civilians according to political—and at times, ethnic and religious—affiliation.

In the years since the post-election crisis, dozens of Gbagbo’s supporters have been tried in Ivorian courts, leading to accusations that the justice system is pursuing “one-sided” justice. The shoddy manner in which several of these trials have been conducted, falling far short of international fair trial standards, has fueled these accusations.

The reality, though, is that Ivorian courts have failed to deliver justice to victims from both sides of 2010-11 crisis. Instead of addressing the extrajudicial killings, torture and rape that pro-Gbagbo forces committed, the cases brought against Gbagbo’s allies have focused on their role in threatening state security during the post-election crisis and subsequent attacks in 2012. Although Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé, his former youth minister, are on trial at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, the only trial so far in Ivorian courts for similar crimes was that of Gbagbo’s wife, Simone. She was acquitted in May 2017 after a trial marred by due process concerns and the inadequacy of the prosecution’s investigation.

Ivorian courts have done even less to hold to account President Ouattara’s allies for abuses during the 2010-11 crisis, which included sexual violence and targeted killings of men from ethnic groups perceived as loyal to Laurent Gbagbo. Although several high-ranking pro-Ouattara commanders are among more than 30 military and civilian officials whom Ivorian judges have charged with human rights crimes during the 2010-11 crisis, none have been brought to trial. Indeed, several army commanders implicated in serious human rights abuses during a 2002-03 armed conflict and again during the post-election crisis were promoted in January.

The International Criminal Court is investigating abuses by both sides during the 2010-11 crisis and will certainly seek to try members of pro-Ouattara forces if they are not prosecuted in Côte d’Ivoire. Ouattara, however, who has refused to transfer Simone Gbagbo to The Hague, has said that all future trials related to the post-election violence will be held in Ivorian courts.

If that is to be the case, now is the time for the Ivorian justice system to show that it is committed to fair and impartial justice for all those implicated in past human rights abuses, regardless of political affiliation. Although Ivorian judges have made significant progress in investigating the atrocities of the 2010-11 crisis, their work will only become meaningful to victims when the alleged perpetrators appear in court.

The government should give judges the support and resources they need to expeditiously complete their investigations and to bring to trial human rights violations committed during the 2010-11 crisis, including by pro-Ouattara forces. The government should also keep its repeated promises to eliminate obstacles to closing investigations, such as the need to exhume mass graves that hold clues about how victims died.

Ivorian prosecutors and judges should also ensure that all those accused of crimes related to the post-election crisis and its aftermath receive a fair trial, including Gbagbo’s former allies. Trials that do not meet due process standards undermine the credibility of Côte d’Ivoire’s courts and fail to do justice to victims and defendants alike.

….

Yacouba Doumbia is the president of the Ivorian Movement for Human Rights.

Drissa Traoré is the vice-president of the International Federation for Human Rights.

Jim Wormington is an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch.