(Berlin) – Russian police have systematically interfered with the presidential campaign of Russia’s leading political opposition figure Alexei Navalny, Human Rights Watch said today. Police across Russia have raided Navalny’s campaign offices, arbitrarily detained campaign volunteers, and carried out other actions that unjustifiably interfere with campaigning. In addition, radical nationalists and pro-Putin groups have physically attacked and threatened campaigners, and official investigations into these incidents have not been effective.

“The pattern of harassment and intimidation against Navalny’s campaign is undeniable,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Russian authorities should let Navalny’s campaigners work without undue interference and properly investigate attacks against them by ultra-nationalists and pro-government groups.”

In December 2016, Navalny announced he would run in Russia’s March 2018 presidential election. To date, he has opened more than 60 campaign offices in different regions of Russia. The extensive police harassment, and attacks on the local offices and campaigners by radical nationalist and pro-Putin groups in spring and summer this year clearly aim to intimidate campaigners and stifle the campaign, Human Rights Watch said.

Navalny, an anti-corruption activist, is formally disqualified from the presidential race due to an outstanding criminal conviction, the result of a politicized, unfair trial.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Navalny campaigners in Kazan, Krasnodar, Rostov-on-Don, Kaliningrad, Irkutsk, Khabarovsk, St. Petersburg and Moscow and reviewed official documents related to the authorities’ actions and complaints to the police, as well as relevant public information including social media postings and videos.

The campaigners described a wide range of methods used to interfere with the campaign. Police have searched campaign offices, seized campaign materials or equipment, and intercepted and confiscated shipments of campaign materials under vague pretexts of “extremism” allegations. Authorities have refused to authorize Navalny’s campaign sidewalk displays, and have detained campaigners on groundless charges of holding unauthorized public gatherings, and for alleged unlawful campaigning activity.

Authorities have also launched criminal inquiries into campaigners’ activities, including for arbitrary violation of lease agreements and other contracts, and distribution of extremist materials. They have also raided the homes of local campaigners and their relatives, seizing equipment, campaigning materials, and other documents. Russia’s specialized anti-extremism police units appear to play an important role in the crackdown.

“The use of specialist police and the label of ‘extremism’ as a pretext for raids, confiscations, and detentions suggests that authorities think it’s ‘extremist’ just to challenge President Vladimir Putin,” Williamson said.

Navalny campaigners and offices across Russia have also faced an increasing number of attacks by ultra-nationalist groups and activists. The attacks range from vandalizing campaign offices or campaigners’ homes, storming into meetings, destroying equipment, blocking the entrance to campaign events, and severely damaging or even burning campaigners’ cars. Attackers have also physically assaulted campaigners, pushing them, beating them, and throwing eggs and other objects at them. They have also carried out bomb scares and thrown a Molotov cocktail at the campaign office in the Stavropol. In some cases the attackers seek to hide their identities, while in other cases the assailants do not hide their identity but rather boast about their actions on social media.

In some of the mob attacks, police merely stood by and did nothing or arrived too late to catch the attackers. When campaigners filed complaints, authorities dutifully registered them, but typically failed to carry out an effective investigation, and in at least one case accused the campaigners of staging the attack for self-promotion.

“Navalny’s campaigners are getting hit from two sides – the ultra-nationalist and pro-government thugs who openly attack them with impunity, and officials, who use lame pretexts to detain and harass them,” Williamson said. “The message is not subtle and the result is the further elimination of any real alternatives in Russia’s political system.”

Navalny’s Campaign

Alexei Navalny’s platform focuses on such issues as ending corruption and inequality, accountability for law enforcement and security agencies, and reversing Russia’s alleged growing isolation. In February 2017, Navalny opened his first campaign office in St. Petersburg. By August, 62 campaign offices were operating in different regions of Russia, with another 15 expected to open later in 2017. On March 20, when Navalny attended the opening of his office in Barnaul, the capital of Russia’s Altai region, unidentified men pelted him with capsules of bright green antiseptic solution.

Throughout the spring, anti-Navalny activists attacked him in other cities, pelting him with eggs and cake. In April 27, when he was leaving his office in Moscow, three men threw a harsh solution in his face, burning of one of his eyes and resulting in a temporary partial loss of vision. Though video footage enabled Navalny to identify the attackers, police suspended the investigation in June, claiming they could not establish the perpetrators’ identity.

On June 23, Russia’s Central Election Commission stated that Navalny could not be a presidential candidate due to his criminal conviction. In 2013, Navalny was found guilty of embezzlement and handed a five-year suspended sentence. The case involved allegations that in 2009, while he was an advisor to the governor of Russia’s Kirov region, he used his position to arrange for a company owned by the regional government to sell timber to another company, which resold it at a higher price. In 2016, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled that the case violated Navalny’s right to a fair trial, and that his actions did not amount to embezzlement. Russia’s Supreme Court then sent the case for a re-trial, and in February 2017 a district court in Kirov once again delivered a guilty verdict.

The head of Navalny’s countrywide campaign, Leonid Volkov, stated on social media that the conviction will not stop Navalny running for president. Volkov also said that Navalny was planning to bring further cases to the ECtHR and explore other legal avenues to enable him to run.

Regional Campaigners: Harassment by Officials

Navalny’s campaign has faced harassment and interference by police and other officials in Moscow; the far east, including Vladivostok and Khabarovsk; in Oryol and other areas in central Russia; in Siberia, including Novosibirsk and Irkutsk; in Russia’s northwest, including St. Petersburg and Vologda; in the Volga region, including Nizhny Novgorod and Kazan; and in the south, including Krasnodar and Rostov-on-Don.

Police Raids and Confiscation of Campaign Materials

Navalny’s campaign coordinator in Kaliningrad, Egor Chernyuk, told Human Rights Watch that police raided the campaign office when it opened in July:

The day after we opened the office [July 7], police searched [it]… they seized all [our] campaign materials, except the posters and the banners, to check them for extremism… It’s been weeks [close to six weeks] and they still haven’t returned them.

Chernyuk said that when he went to the Kaliningrad airport in early July to pick up a shipment of campaign newspapers, which report on corruption and also on Navalny’s program, an airport representative and a police officer informed him that the police had seized the shipment to examine it for extremist or other prohibited content. The officer did not provide a receipt, and the newspapers remain confiscated. In late August, Volkov published an allegedly leaked order by a high-level official from the Interior Ministry’s transportation department. The order, dated June 4, called on local police to seize, “under one pretext or another,” a large shipment of Navalny’s campaign materials en route to Chernyuk.

Elvira Dmitrieva, the campaign coordinator in Kazan, told Human Rights Watch that on July 7, police arrived at the local campaign office for what they called an “inspection” and seized 10,000 campaign flyers, alleging that some “information needed to be verified,” but otherwise providing no grounds for their actions. The materials are still with the police.

Also, on July 12, Delovaya Liniya, a private postal company, informed Dmitrieva that on July 4, the police had seized a large shipment of campaign newspapers that she was expecting. The company provided no further information. At about the same time, media reported similar developments in Ufa, Saratov, and Nizhny Novgorod. A spokesman for Delovaya Liniya told the press that “in several cities, cargo [meant for Navalny’s local campaign offices] was seized by police officials” and “Delovaya Liniya staff are obligated to comply with demands by state authorities.”

Miroslav Valkovich, the campaign coordinator in Krasnodar, told Human Rights Watch that police searched the campaign office there on July 7 and seized 940 campaign newspapers. Valkovich said that when asked about the reasons for their actions, police officials vaguely referred to a “complaint” they had supposedly received but refused to provide any detail. The police have not returned the newspapers.

On July 11, police raided the campaign office in Khabarovsk. They told the regional coordinator, Alexei Vorsin, that they were looking into allegations of “unlawful campaigning activities” and seized 2,000 flyers for further examination. Vorsin told Human Rights Watch that police have not returned the flyers.

Sergei Bespalov, the campaign coordinator in Irkutsk, told Human Rights Watch that in July the police had searched the office three times, alleging “unlawful campaign activity,” and seized 22,200 flyers and 12 campaign street displays. Bespalov said that police sent the materials for linguistic review. On August 7, police seized 3,000 newspapers from a shipment Bespalov was picking up at the airport. The officers claimed that the police had received two phone calls from “concerned citizens” warning them that the shipment contained extremist materials and dangerous objects. The newspapers, the displays, and the flyers are still with the police.

When police raided Navalny’s headquarters in Moscow in July, they forcibly detained a volunteer and hit him in the face, according to media reports. The man had to be hospitalized for treatment.

Arbitrary Detentions and Other Interference

All the campaign regional coordinators interviewed by Human Rights Watch described official interference with their work, including through arbitrary detention, administrative penalties, and arbitrary refusals to approve setting up campaign displays.

Bespalov told Human Rights Watch that police in Irkutsk regularly detain volunteers when they hand out flyers, and mostly release them quickly without charge, but refuse to return the flyers. One had to pay a fine of 1,500 rubles (approximately US$25) for supposedly “unlawful campaigning activity.” Bespalov said police also put pressure on the parents of Navalny’s teenage supporters, phoning them, inviting them for informational “conversations,” insinuating that their children could get into trouble, and urging the parents to discourage them from any involvement with the campaign and anti-corruption protests.

The campaign’s St. Petersburg coordinator, Polina Kostylyova, told Human Rights Watch that setting up a campaign sidewalk display in the city center is “next to impossible,” and that municipal authorities authorize them only in the outskirts (sidewalk displays, typically large signboards, with campaigners nearby handing out leaflets, are generally registered as pickets and require authorization by local authorities).

From February through to mid-August, St. Petersburg authorities rejected 10 notifications by Navalny’s local campaigners to set up campaign displays in the city center. In four instances, Kostylyova appealed the decision to a court and lost. One case, involving a display that would have been 200 meters from a church, was particularly absurd, she said:

In early July, we were planning to set up a campaign display in the city center, not far from the metro. We wanted to have the display at the entrance to a garden, which [in turn] led to a church. So, the municipality argued that having a public event anywhere near a Russian Orthodox church could result in offending religious feelings of believers [a criminal offense under Russian law].

The municipality also noted that there were several major roads nearby and the display could distract drivers and pedestrians.

Kostylyova and Valkovich said police often detain campaigners handing out flyers in St. Petersburg and Krasnodar respectively, hold them in custody for several hours without explanation and then release them without charge.

In Krasnodar, the municipality allows campaign displays to be set up only “in the open fields” outside the city, Valkovich said.

In Kazan, police detained five campaign volunteers as they were setting up a display on May 14 in the city center. According to Dmitrieva, police officers ordered the volunteers to remove the display because the municipality had not authorized it. They tried to cooperate, but police had seized the tools needed to dismantle it. When they told police this, they were taken to the station for the night. The next day, a local court sentenced one to 10 days detention for disobeying police orders. Two weeks later, the others were sentenced to 10 to 12 days’ detention for disobeying police orders and/or violating regulations on public gatherings.

Kazan police detained two more volunteers on July 8 as they were handing out campaign flyers while standing at a significant distance from one another, and charged them with violating regulations on public gatherings, “the distance between them being less than 30 meters.” A local court sentenced one to 30 hours of community service and the other to 15 days’ detention.

On August 4, the campaigners made another attempt to set up a display in Kazan, near a metro station. Anti-extremism police showed up, seized the display, and took the activists to the station. The campaigners were allowed to leave, but police kept the display for “expert analysis.” On August 6, the campaigners again tried to set up a display. While they were assembling it, anti-extremism police arrived and told them to take it down because it was identical to the one being examined for extremism. That month, anti-extremism police detained Ruslan Shaveddinov, Navalny’s campaign press secretary, when he was visiting the Kazan office. Police claimed that they had information regarding Shaveddinov making “public calls for engagement in extremist activities” – a crime under Russian law. Three hours later, they released Shaveddinov without charges.

On August 23, a court in Kazan sentenced Dmitrieva to 10 days’ detention for “repeated violation” of regulations on mass gatherings. The charges stemmed from an announcement on the Team Navalny-Kazan group page, on VK – the top social media platform for Russian-speakers – calling on all Navalny supporters in Kazan to stop by the campaign office, pick up campaign newspapers and flyers, and hand them out. The judge accepted the police argument that as the administrator of the Team Navalny-Kazan account on social media, Dmitrieva had aimed to encourage an “unlimited number of people… to take part in an unsanctioned public event.”

Vorsin, in Khabarovsk, told Human Rights Watch that local authorities closely monitor their campaign displays and threaten activists with detention and other sanctions. He said:

A representative of the municipality stands by the whole time and literally controls each and every step of our volunteers. One step to the left, one step to the right and they are up in arms, calling it an unlawful public action, saying they’d be calling the police to have charge sheets issued.

Attacks by Radical Nationalist and Pro-Putin Groups

Some of the attackers appear to be part of organized groups, such as the South East Radical Block (SERB), Cossacks, the National Liberation Movement (NOD), and Putin’s Brigades.

SERB is a small ultra-nationalist group that first emerged in 2014 in Ukraine, when it attempted to take over the Kharkiv city administration. To avoid criminal prosecution, some members fled to Russia, where they have attacked several pro-democracy activists and opposition figures, including Navalny in Moscow in April 2017.

Cossacks identify themselves as a separate ethnic group in Russia, supposedly several million strong. They are known to maintain militias, especially in the south of Russia, where in some places they have close ties to law enforcement. Cossacks have openly disrupted numerous events and gatherings by Russia’s political opposition and civic activists.

NOD is a pro-Kremlin organization seeking a strong authoritarian rule, and adhering to nationalist ideology. It has several hundred members and has violently attacked its opponents and human rights groups.

Putin’s Brigades is a movement in Krasnodar region that appears connected to a local politician and consists mostly of women past retirement age who supposedly desire to unite all Putin supporters against those who “undermine” Putin’s policies.

Violent Attacks on Campaigners and Those Cooperating with Them

Bespalov, in Irkutsk, told Human Rights Watch that on May 31 several men with clubs and baseball bats beat Vladilen Bugaev, 33, at the local campaign office. Bugaev’s father is the landlord of those premises. Bugaev and two witnesses to the attack said the assailants screamed, “We know everything about you – you’re renting this office to Navalny…” They also ordered Bugaev to break the lease.

Bugaev said he was in the office at 6:30 p.m. with two friends. The office door was unlocked, and three men walked in asking about a company that had relocated from the building. The visitors left and then returned with another three to four men. Several of them attacked Bugaev, kicking and punching him and beating him with baseball bats, while ordering him to evict Navalny. The others pushed his friends into a corner and held them there – asking their names and about their links to Navalny.

Bugaev described the assailants as “well trained” and said in a media interview that he saw a gun slip out of one man’s pocket. “When they beat you, they beat you, when they are out to kill, they kill, not talk. If they had wanted to kill me they would’ve killed me,” he said. Bugaev sustained multiple hematomas and abrasions and had to get six stitches and other medical treatment.

The police promptly opened an investigation. “There were several security cameras . . . and the men didn’t try to conceal their identity, hide their face... It was all out in the open,” Bespalov said. Bespalov said police questioned Bugaev, watched the surveillance videos with him, and supposedly established the identity of the main perpetrators. The case was then transferred to the Irkutsk regional police.

Bespalov and his fellow campaigners told Human Rights Watch they are now concerned that the investigation has stalled. Bespalov also flagged that prior to finally signing a lease agreement with Bugaev’s father, he tried renting six different properties for the campaign office. All the landlords seemed accommodating at first and then refused to sign the lease at the last moment. One told Bespalov that he changed his mind after some “bandits” paid him a visit and coerced him into pulling out.

Attacks on Campaign Offices and Campaigners’ Homes and Vehicles

Kostylyova, in St. Petersburg, told Human Rights Watch about an arson attack at the local campaign office before the March 26 countrywide anti-corruption protests initiated by Navalny. Early on the morning of March 23, the police called her saying that someone had set the office door on fire overnight, causing considerable damage. The police investigation into the attack has yielded no results.

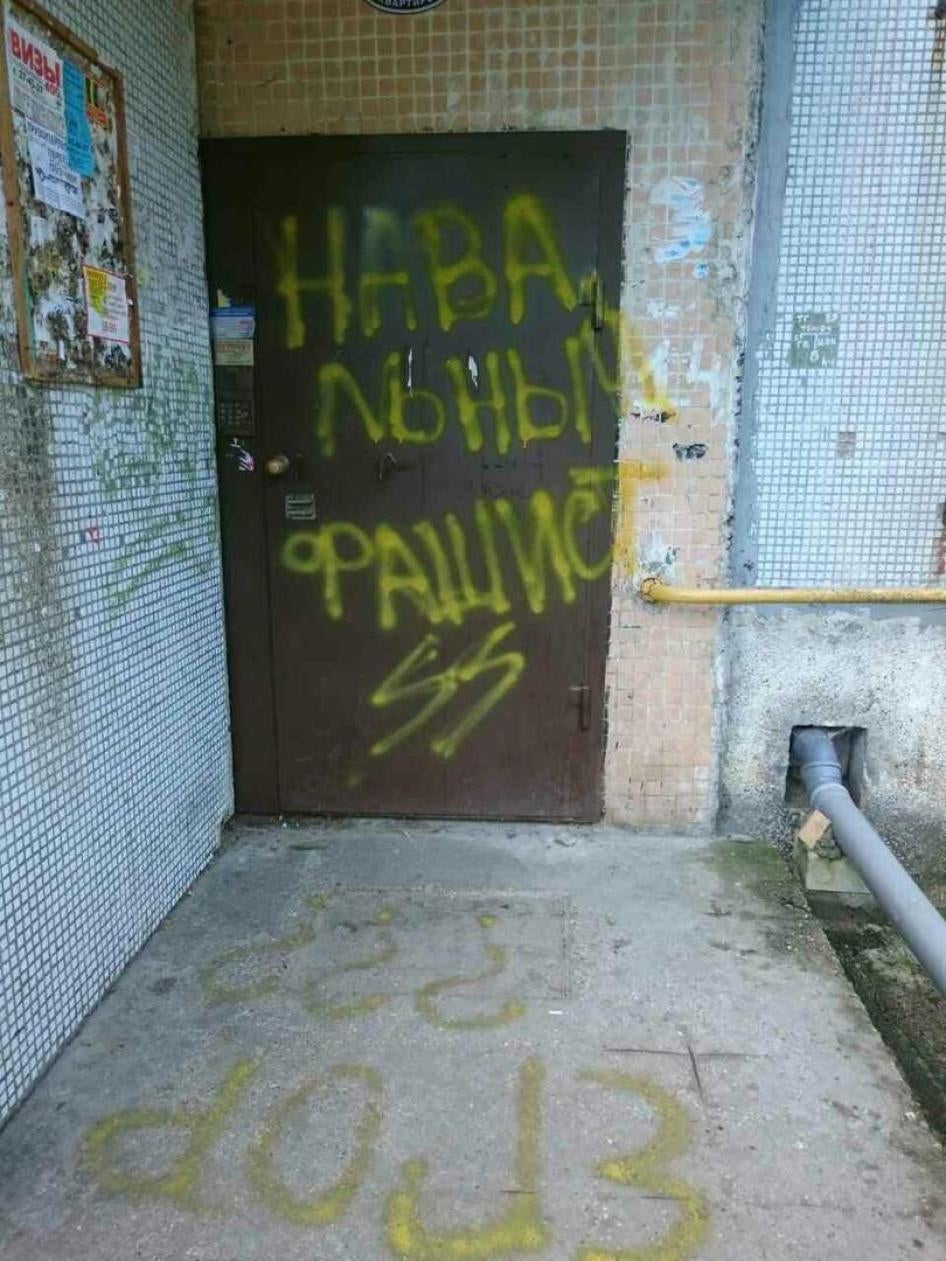

Chernyuk in Kaliningrad told Human Rights Watch that on July 6, the day before the opening of the local office, an unknown individual painted “Navalny is a fascist” on the office door. On July 21, someone pelted the windows with small metal balls, apparently from a slingshot, breaking one. Chernyuk’s home and the homes of several volunteers sustained damage from similar attacks. Chernyuk said:

[Some people] repeatedly vandalize the lobbies of the buildings where our volunteers live – they paint obscene pictures on the walls and write threats and all sorts of offensive comments. Same goes for me. Also, on July 11, someone shot a paintball gun at my apartment window, splattering it with paint. And on August 1, they threw a brick into my apartment, shattering the window.

Chernyuk said police officials arrive when called, but have not conducted an effective investigation into any of the incidents. His appeal to the governor of Kaliningrad about the persistent attacks has received no response.

Anastasia Deyneka, campaign coordinator in Rostov-on-Don, told Human Rights Watch that her predecessor, Elena Kulikova, had her vehicle damaged by unidentified individuals on July 26. The assailants slashed the tires and splashed the car with ink. The police registered the complaints but otherwise the investigation has gone nowhere. Four weeks later, Kulikova resigned from her position citing a busy schedule.

Deyneka also described how local authorities, Cossacks, and NOD disrupted the opening of the campaign office in the city. On April 8, Navalny’s national campaign boss, Volkov, planned to mark the opening by holding a news conference and meeting with local supporters at the Railroad Workers’ Culture Palace. That morning, however, the venue suddenly canceled the reservation because of an ad hoc training organized by the Federal Security Service. The campaign decided to hold the events instead at the Ermitazh Hotel, where Volkov was staying. A large group of men dressed in Cossack attire, some armed with traditional Cossack whips, blocked the hotel’s entrance. They were soon joined by a group of NOD members with anti-Navalny posters.

Navalny’s supporters called the police. Although several police vehicles arrived, the officers watched as the Cossacks and their allies threatened the Navalny supporters with whips, yelled at volunteers, pushed and refused to let them through, and demanded that Volkov come out “to talk.” When Volkov eventually complied, the Cossacks and NOD members shouted abuse and demanded that he leave the city. Volkov returned to the hotel and met with volunteers who had snuck past the Cossacks.

Valkovich, in Krasnodar, also described to Human Rights Watch an attack on local campaigners. On April 20, a pro-Navalny Cossack activist, Evgeny Panchuk, gave a news conference at the local campaign office criticizing Russia’s government and expressing support for Navalny. Men in Cossack attire stormed into the room shouting abuse. They ransacked the premises, threw eggs and flour at Panchuk, punched him and several other Navalny supporters, and left. The office called the police, who arrived and questioned some of those present. The investigation has yielded no results.

Valkovich also said Putin’s Brigades engaged in frequent constant attacks against the Krasnodar campaign office. He said that since spring 2017, Putin’s Brigades activists – mostly women past retirement age – had raided the office 14 times, bursting in, ransacking the premises, throwing things, damaging office equipment, yelling, and stealing campaign newspapers and flyers. “At first, they just stopped by to talk to us… And then, they started stealing campaigning materials from the office and damaging our property. What they started doing was full blown hooliganism. Last time [on August 3] they broke the lower glass panel on the office door.”

With each raid, the campaigners called the police, but in some cases the attackers fled before police showed up and in others, the officers simply stood there, asked the women to leave, but did not physically remove them or take other action. Valkovich said the authorities registered his complaints after every incident, but not one has resulted in any penalty against the offenders, and the raids have continued.

Since it opened in April, Navalny’s campaign office in Stavropol, another region in southern Russia, has been reporting to media police interference and threats from non-state actors, including Cossacks. Late at night on June 10, unknown assailants threw a Molotov cocktail into the office, shattering a glass panel. The authorities opened an investigation, but are treating as possible suspects Yaroslav Sinyugin, who coordinated Navalny’s campaign in Stavropol, and several of his colleagues.

Sinyugin said, “The arson attempt is used by the investigation to put pressure [on the campaigners] … Law enforcement officials are attempting to make one of the activists testify against me.”

On August 19, Sinyugin resigned. Two days earlier, unidentified individuals had slashed the tires on his car. “For me, family comes first. I really like my job with the campaign but it entails particular risks,” he explained in an interview about his resignation.