Surprise turned to confusion, then to horror, when the children at Kiata primary school realized that the soldiers they had spotted at the bottom of the hill were heading for their school and its occupants.

As the soldiers reached the hilltop school in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, students scattered in all directions, scared of the armed men and what they might do.

Those who failed to escape the courtyard before the soldiers entered were caught, beaten and forced to help as the armed men converted the school into their temporary base. The soldiers made the children fetch water, steal food from nearby farms and chop up their school desks for fire wood. When one of the captured boys refused to obey, a soldier sliced his arm with a knife. If the older girls resisted the soldiers’ advances the men would rip their clothes, one student told my colleague.

The capture of Kiata primary school in late 2012 features in a new report by Human Rights Watch, which documents the far-too-frequent misuse of schools by the Congolese army and various armed groups in areas of the country that are still affected by conflict. In fact, our investigation shows, the presence of armed men inside schools is a far-too-familiar sight for many children in Congo who are yearning to learn.

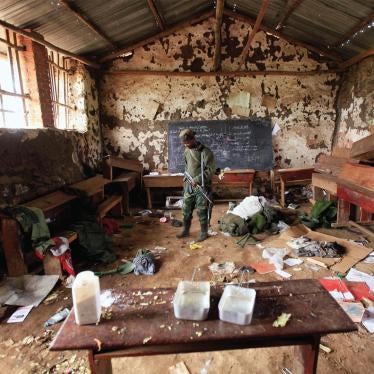

When fighters take over a school, they sometimes only make use of a few classrooms or the playground; at other times, however, they convert the entire school into a military base, barracks or training grounds. As the students held captive at Kiata school attested, troops occupying schools means students and teachers risk being unlawfully recruited into armed groups, forced to work without pay, beaten and sexually abused.

The military use of schools also damages and destroys an education infrastructure that is already insufficient and of poor quality. Fighters who occupy schools frequently burn the buildings’ wooden walls, desks, chairs and books for cooking and heating fuel. Tin roofs and other materials may be looted and carted off to be sold for personal gain. And what makes matters worse, schools that are being used for military deployments become targets for enemy attacks.

Even once vacated, a school may still be a dangerous environment for children if troops leave behind weapons and unused munitions. I visited one school in Congo that had been used as a temporary base, where the occupiers had dumped some of their unused munitions in the school latrines before leaving. The rockets left immersed in the waste required demining experts to removea process that was only completed more than seven months later.

Sadly, the practice of armies using schools for military purposes is not unique to Congo. It happens in the majority of countries with armed conflict. All across Africa, from Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan to Sudan, the occupation of schools by armed forces has deprived children of a safe learning environment and the right to education.

Even troops deployed as peacekeepers by the African Union have been found to be using education institutions as bases in the Central African Republic and Somalia– a particularly troubling development.

But there is hope. Earlier this year, a group of countries from around the world committed to do more to protect students, teachers and schools during times of armed conflict. The Safe Schools Declaration, as the commitment is known, includes an agreement to ensure that military trainings, practice and doctrine emphasize the need to protect schools from military use.

To date, 49 countries have joined this Safe Schools Declaration. Better yet, 13 African countries, including many with recent experiences of the military use of schools in their own territory, were among the first to endorse.

To ensure that its children can learn for liferather than having to run in fear for itthe Congolese government ought to refrain from using schools for military purposes and join the Safe Schools Declaration. In fact, if all nations across the continent were to rally around this goal, the continent could become the first to have universally endorsed the Declaration.

And if the African Union were to re-examine its rules and procedures for its peacekeeping forces and, as the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations did in 2012, ban all infantry battalions from using schools during their operations, African kids would be that much safer and no longer scarred for life like the boy our report names Amani.

A 10-year-old primary school student, Amani was held in Kiata school for six days. When we met him, he showed off the scar on the bridge of his nose. The soldiers who had occupied his school, had forced him to chop up the school desks. A piece of wood had split off and hurled in his face as he chopped. When Amani was finally allowed to return home, his parents asked if the soldiers had beaten him. When he told them what had happened, they responded: “Understand, child, life is like that.”

But if Congo and other countries across the continent would agree to restrain their armies from using schools, then life needn’t be like that for children in Africa and elsewhere.