It’s hard to find sadder places in Nigeria than those that have suffered attacks by Boko Haram, the underground fundamentalist Islamic organization. Christians are fearful of attending church. Muslims, who also face attacks by Boko Haram, express concern that government security forces indiscriminately hunting down the group’s members consider their entire community to be the enemy. As one Muslim civic activist in this northeastern Nigerian city put it: “People don’t know who to be more afraid of — Boko Haram or the police.”

Far from international headlines, and beyond the blustery charges and countercharges of who is really to blame for the violence, Nigerians are under assault by both Boko Haram and the country’s heavy-handed security forces.

From its base here in northern Nigeria to as far south as the capital, Abuja, Boko Haram (whose name roughly translates as “Western education is sinful”) terrorizes Nigerians with rifle attacks and suicide car bombs. The group has shown a particularly relentless focus on blowing up police stations and hitting both secular targets (such as pubs and markets) and religious targets (such as churches full of worshipers). Since 2009, more than 1,500 Nigerians have died at the hands of Boko Haram, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch.

After a recent research mission to Nigeria, Human Rights Watch concluded from the severity and extent of the abuses that Boko Haram’s violations probably constitute crimes against humanity and should be investigated and prosecuted immediately.

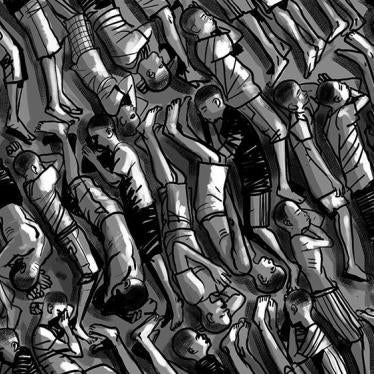

Meanwhile, the Nigerian army and police have responded to Boko Haram both cruelly and clumsily. The latest atrocity: On Monday, soldiers allegedly went on a rampage in Maiduguri after a roadside bomb, suspected to have been planted by Boko Haram, killed three soldiers near the University of Maiduguri, a military spokesman here told reporters on Wednesday. In retaliation, news reports say, the soldiers randomly gunned down residents near the attack. The military spokesman said only one civilian died, but reporters on the scene counted 30 bodies of unarmed people in the area.

Over the past three years, Nigerian soldiers and police have carried out mass roundups, kept people in secret prisons without recourse to lawyers or courts, burned down homes and shot and killed detainees. Human Rights Watch has documented more than 50 extrajudicial killings by the police and military that should be investigated and prosecuted.

It is still not clear whether these crimes are systematic or widespread, and other reports of abuses need further examination to determine whether they are crimes against humanity under international law. Still, Nigerian authorities have rarely investigated or tried those who commit the crimes that Human Rights Watch has documented.

All this adds up to a horrific situation for Nigerians. Victims and civic activists repeatedly told Human Rights Watch researchers in May that abuse by soldiers and police — everything from taking bribes to torture to murder — undermines support for the forces of law and order. To curtail Boko Haram effectively, security forces need community residents’ cooperation. The prevalence of wrongdoing by government forces both prevents that collaboration and nourishes Boko Haram’s narrative that the group is simply fighting a corrupt and incorrigible regime.

On Oct. 1, Nigeria commemorated 52 years of independence. On the margins of the celebration, commentators generally lamented the country’s decline. Poverty afflicts 60 percent of the population and is rising, the gap between rich and poor is widening, education is in shambles, and the country’s oil wealth is literally siphoned off in the Niger Delta.

Over the past several years, Human Rights Watch has documented political corruption and its effect on Nigeria’s failure to provide basic services and security. Northern Nigeria, Boko Haram’s main area of operation, lags other parts of the country in economic development and employment. That deprivation creates fertile terrain for the group but of course does not justify its barbaric attacks.

To win its battle against Boko Haram, the government must make ending security-force lawlessness a primary objective. Officials should also hear and act on the concerns of the beleaguered residents of places such as Maiduguri, who are caught in the crossfire between an Islamist group bent on destruction and security forces whose indiscriminate attacks also fuel the spiral of violence in Nigeria.

Given that, in the first nine months of this year, more deaths were recorded in the struggle between Boko Haram and the security forces than in 2010 and 2011 combined, the need for action is urgent. Denials by the government and Boko Haram will only prolong the agony of northern Nigerians.

Daniel Williams is a senior researcher in the emergencies division of Human Rights Watch.