A 50-year-old man with links to the extreme right opens fire on Senegalese street vendors in Florence, killing two and seriously wounding three others. He then kills himself. An angry mob attacks a Roma camp in Turin after a teen-aged girl falsely claims she had been raped by two Roma men.

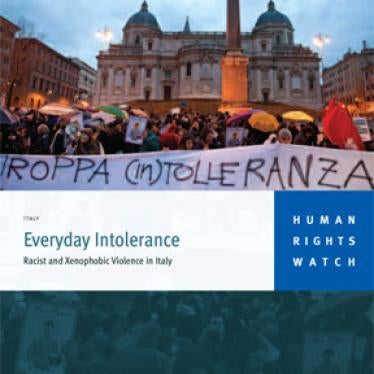

These events, two days apart in mid-December, serve as a stark reminder of increasing intolerance and racism in today’s Italy. In recent years, immigrants, Italians of foreign origin, and Roma have been assaulted, stabbed, shot at, and murdered.

These attacks are not isolated incidents but part of a wider pattern of racist violence. Mob violence against Roma in Naples in May 2008 and attacks on African migrant workers in Rosarno, a small town in the southern region of Calabria, in January 2010 made international headlines.

In my own research on the subject for a report earlier this year, I spoke with the father of Abdoul Guiebre, a young Italian of Burkina Faso origin, who was beaten to death on a Milan street by the father and son owners of a bar in September 2008 after a petty theft. Marco Beyene, an Italian of Eritrean origin, told me how he was beaten by two men in a Naples in March 2009 to shouts of “shitty nigger” (“negro di merda”). Mohamed and Mahbub Miah, two brothers from Bangladesh, told me about the attack on their bar in Rome by a group of 15 to 20 people in March 2010, injuring four people and damaging the property.

Racist violence is a growing problem across Europe. But Italy’s response has been notably weak.

The mayors of Florence and Turin rightly condemned the recent violence, and President Giorgio Napoletano called on public authorities and civil society to combat “all forms of intolerance.”

Yet officials have generally played down racism as a serious issue, while anti-immigrant and anti-Roma rhetoric has become a staple of political discourse and media reporting in recent years, nurturing a climate of intolerance.

The government of former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, in coalition with the openly anti-immigrant Northern League party, adopted “emergency” decrees in 2008 to facilitate strong-handed measures against undocumented migrants and Roma; passed legislation in 2009 to make undocumented entry and stay in Italy crimes; and tried to impose harsher penalties for crimes when committed by undocumented migrants.

The political failure to acknowledge racism as a growing problem has clear policy consequences. Police, prosecutors and judges do not receive specialized training that would help them identify, investigate, and prosecute hate crimes. Very few attacks are prosecuted as hate crimes, even though Italian criminal law allows for harsher prison sentences for crimes aggravated by racist motivation. The courts often rely on a narrow definition that limits its use to crimes where racism is the sole motive for an attack.

Failure to identify hate crimes, combined with underreporting—especially by undocumented migrants, who fear the police—means official statistics are low. This is in turn is used by Italian officials to justify claims that racially aggravated violence is rare—a vicious circle that effectively allows impunity for racist crimes.

Important steps have been taken over the past year, with the support and help of the National Office against Racial Discrimination, to combat intolerance and improve recording of hate crimes. But much more is needed.

That means better training for police, prosecutors and judges, comprehensive data collection, and targeted prosecutions, and a clear recognition of the problem across government, and in society.

Abdoul Guiebre’s murderers were tried and convicted, but not of a hate crime. His father is convinced it was racism: “If my son had had a different color of skin, they wouldn’t have acted like that. They killed him because he was black. My son is dead, but his mother, his brother and his sisters and I die every day.” Violence inspired by racism or xenophobia should be called by its name, to punish those responsible and prevent further suffering.

Judith Sunderland is senior Western Europe researcher at Human Rights Watch.