Ladies and Gentlemen! Behold! The phoenix from the ashes. From the ruins of the CCW emerges the glorious Ottawa Process. And what a wild ride.

From the end of the CCW on May 3rd, 1996 to the signing of the Mine Ban Treaty on December 3rd, 1997, there was an intense whirlwind of activities, events, conferences, and meetings. Some sponsored by governments, some by NGOs. At the international, regional, and national levels. Each building upon the other, creating a relentless momentum.

Some were used to develop the treaty text—in record time. Many others were used to build political will, to convince everyone that a comprehensive ban was the only solution to the global landmine crisis. All were very concrete and action-oriented, resulting in action plans with specific tasks. We always identified who would take responsibility for doing what.

Taking action and taking responsibility were hallmarks of the Ottawa Process from the beginning.

The Ottawa Process has been hailed as a new kind of diplomacy, one marked above all by partnership—partnership of NGOs led by the ICBL, dedicated governments, the ICRC, and UN agencies (especially UNICEF in the crucial early years). A new diplomacy in which civil society played a major role, indeed it largely set the agenda and without question served as the driving force. As one diplomat said at the end of the negotiations on the Mine Ban Treaty, this was the first time civil society demanded urgent global action on an issue with strong national security considerations, and governments actually responded.

It worked because of the partnership, and the focus on the humanitarian impact, and not narrow, perceived military requirements.

It worked because of bold, visionary, and deeply committed individuals. (And I am not just talking about my wife, who you just saw on the video). Personal commitment played a major role. Diplomats and those in the ICRC and UN officials became campaigners! It was a wonderful thing to see and experience. Many embraced “the cause” as their main objective, not always strictly in keeping with their national or organizational positions and instructions. They were willing to take risks.

And it worked because of our broad, global coalition, with simultaneous action on dozens of fronts, from an incredible range of groups all affected in one way or another by landmines, providing both field expertise and strong activism in capitals and elsewhere, with each national campaign operating with the freedom to undertake actions that would work best in their particular circumstances.

By the time we got to Oslo for the formal negotiations in September 1997, we were feeling good about the draft treaty and the number of governments supporting it. But, privately, we were worried about how fragile it was, and fearful it could fall apart. Some nations had come with major, crippling amendments. I also worried about “death by a 1000 tiny cuts,” with smaller, weakening amendments undermining the whole.

But an amazing thing happened. The treaty got stronger over the three weeks, and emerged as a ground-breaking new international law—combining comprehensive disarmament provisions with vigorous humanitarian requirements for mine clearance, risk education, and, for the first time, victim assistance.

Three weeks later, the Nobel Committee announced that the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize would be awarded to the ICBL and its coordinator, Jody Williams. This was a great and unexpected honor, but we were very clear that our main prize was the Mine Ban Treaty, not the Peace Prize. Our only concern was to use the Peace Prize to further the treaty and our efforts to rid the world of landmines.

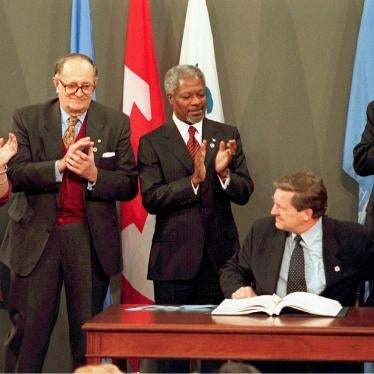

And the Peace Prize did help. We suddenly found ourselves meeting with Ministers and even heads of state, instead of Third Secretaries in Embassies. But the best measure of the impact of the Peace Prize was this: a total of 89 nations adopted the Mine Ban Treaty in September; before the Peace Prize announcement, most of us hoped that we would just be able to get all of those 89 to sign in December; instead, less than one month after the Peace Prize announcement, 122 nations signed the Mine Ban Treaty in Ottawa, a huge and sudden increase in those embracing the ban.

You only get the Nobel Peace Prize once. And many thought the Ottawa Process too would be a one-off, a one-time occurrence. That it was only possible due to a unique set of circumstances.

But this has been proven wrong. Elements of the Ottawa Process were soon incorporated into the successful campaigns on the International Criminal Court and on child soldiers. And, of course, the Ottawa Process served as the model for the Oslo Process that resulted in a comprehensive ban on cluster munitions through the Convention on Cluster Munitions. And the reverberations of the Ottawa Process and Oslo Process were also felt strongly in Geneva during the failed CCW negotiations on cluster munitions the past two weeks.

Ladies and gentlemen! We will be hearing much more this afternoon, but hear this now: the Ottawa Process is still alive! Long may it prosper!