(New York) - The European Union and the United States should re-examine their relationships with the Uzbek government in light of its atrocious rights record, Human Rights Watch said today on the eve of the sixth anniversary of the government massacre at Andijan, Uzbekistan. Both the EU and the US have been enhancing their relationships with the Uzbek government.

"The EU and the US have to hold the Uzbek government to account for the Andijan massacre and for the unrelenting repression that continues to this day," said Rachel Denber, acting Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. "They should make clear there will be no deepening of relations without concrete human rights improvements and reiterate calls for justice for this terrible atrocity."

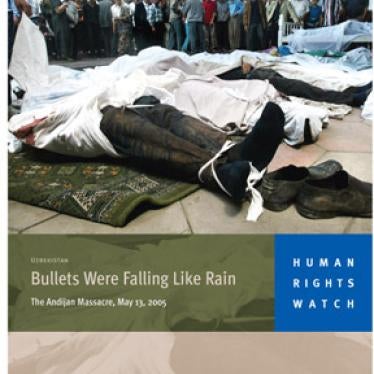

On May 13, 2005, hundreds of largely peaceful protesters were killed by Uzbek government forces indiscriminately and without warning. No one has been held accountable for the killings, nor has the Uzbek government ceased its relentless persecution of those whom it suspects of having ties to the protest and of human rights activists and others critical of the government.

The massacre, the Uzbek government's refusal to allow an international investigation, and the ensuing crackdown, led the EU to impose sanctions in October 2005 and to establish a set of human rights criteria for the Uzbek government. The Uzbek government has not met those criteria, but the EU gradually eased the sanctions and in 2009 lifted them completely.

While relations between Uzbekistan and its Western partners have essentially normalized, there is no evidence of improvements in Uzbekistan's human rights record or any sign of political will to address the rampant human rights abuses in Uzbekistan.

In recent weeks, new information has come to light about Germany's payments to Uzbekistan for use of an airbase in Termez for operations in Afghanistan. Germany made no secret about its aversion to the EU sanctions from the outset and actively undermined them. Just weeks after the sanctions were adopted, for instance, it allowed Zokir Almatov, Uzbekistan's interior minister at the time, to travel to Germany for medical treatment, though he topped the list of Uzbek officials banned from EU territory. According to media reports, from 2005 through 2009, Germany paid a total of €67.9 million (US$97.1 million) for use of the Termez base, with the payments rising each year the sanctions were in place and falling in 2008, when the sanctions were almost completely lifted.

"In the wake of Andijan, the German government undermined the sanctions, arguing they weren't effective," Denber said. "If Germany wasn't going to take a principled stand, it should at least have been more honest about why."

According to another document made public by Germany's Green Party, in 2010 Germany paid €15.9 million (US$22.7 milion) to the Uzbek Finance Ministry, in addition to just over 10 million for "rent of objects" and operation fees. Berlin will continue to pay the additional compensation in coming years that it uses the base, the document says.

"It is truly shocking that Germany is paying millions to the Uzbek government with no strings attached," Denber said. "Germany should explain whether it has considered alternatives to Termez, and if so why it has ruled them out in favor of supporting this brutal government."

The EU overall is currently deepening its engagement in Uzbekistan. In January 2011 the European Commission president, Jose Manuel Barroso, received the Uzbek president, Islam Karimov, in Brussels and the EU is seeking to open an EU delegation in Tashkent by the year's end.

Human Rights Watch said that the EU's eagerness to deepen its relationship with Uzbekistan without requiring human rights improvements contrasts with its recent rethinking of its relationships with autocratic governments in the Middle East. In March, Štefan Füle, the European commissioner for enlargement and the EU's neighborhood policy, told the European Parliament that "too many of us fell prey to the assumption that authoritarian regimes were a guarantee of stability in the region." He said that the EU should be on the side of people striving to promote European values.

The United States is also pursuing a policy of re-engagement with Uzbekistan. Congress has expressly restricted assistance to Uzbekistan based on its deplorable human rights record and further tightened those restrictions following the Andijan massacre. But the Obama administration is seeking to re-start assistance and to provide direct military aid, also known as Foreign Military Financing (FMF), to Uzbekistan in 2012.

Uzbekistan is seen as a critical stop in the Northern Distribution Network, through which the United States has sent non-lethal supplies to Afghanistan since 2009, as an alternative to what are viewed as unstable supply lines through Pakistan. Uzbekistan expelled the United States from the Karshi-Khanabad base in July 2005, just after refugees from Andijan were airlifted from Kyrgyzstan to Romania with US assistance.

A US visa ban on Uzbek officials went into effect in summer 2008, and restrictions on foreign assistance remain in place. But it is not clear what steps the administration has taken to promote implementation of the human rights benchmarks attached to the legislation as part of its dialogue with the Uzbek government. The benchmarks include investigating and prosecuting individuals responsible for the Andijan massacre and other criteria such as establishing a genuine multi-party system and ensuring freedom of expression.

Human Rights Watch said that as a condition for deeper engagement with the Uzbek government, the EU should insist that it fulfill the human rights criteria attached to the EU's post-Andijan sanctions: release all imprisoned human rights defenders and political prisoners; allow unimpeded operation of nongovernmental organizations in the country; cooperate fully with all relevant UN special rapporteurs; guarantee freedom of speech and of the media; implement the conventions against child labor; and fully align its election processes with Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) standards.

A September 2010 memorandum outlines how Uzbekistan has failed so far to take "substantive steps" with regard to these criteria.

The US should also insist on the Uzbek government meeting the specific criteria articulated in the EU sanctions language, as well as the broader criteria in US legislation.

"The upheaval in the Middle East should have made clear that unconditional support for supposedly ‘friendly autocrats' is short-sighted and counterproductive," Denber said. "The United States and the European Union should send a clear message to Uzbekistan that brutalizing its own people and stonewalling international reporting comes at a price."

Background

Andijan: May 13, 2005

On the morning of May 13, 2005, gunmen broke into Andijan's prison to release 23 local businessmen who were on trial for "religious extremism" and attacked several government buildings in Andijan. Hours later, thousands of people gathered on the square of their own accord to vent grievances about poverty and government repression. Although a small group of gunmen were on the square, the overwhelming majority of demonstrators were unarmed.

Later in the day, Uzbek security forces indiscriminately shot into the crowd from armored personnel carriers (APCs) and sniper positions above the square. Toward evening, government troops blocked off the square and then, without warning, opened fire, killing and wounding hundreds of unarmed civilians. As they tried to escape, hundreds of people were shot by snipers or mowed down by troops firing from APCs. After the peak of the carnage, government forces swept through the area and executed some of the wounded where they lay.

Government agents made no apparent effort to limit the use lethal force to situations where it was strictly unavoidable to protect lives, as required by international law. The United Nations and other intergovernmental organizations found that the government had used lethal force excessively.

The Uzbek government has refused to allow an independent inquiry into the massacre and denies responsibility for the killings of the unarmed protesters. Meanwhile, President Islam Karimov was among those most vocal in calling for an independent international inquiry into the June 2010 ethnic violence in southern Kyrgyzstan, which included attacks on ethnic Uzbeks.

The government put the Andijan death toll at 187, acknowledging only approximately 60 protester deaths, and attributing all of those to gunmen in the crowd, not to government forces. The real number of civilian deaths is estimated to be several times the official number.

Furthermore, Uzbek authorities suppressed and manipulated information about the massacre and arrested hundreds of the demonstrators and witnesses to the violence. Human Rights Watch documented the stories of many of these men and women, who were arbitrarily detained and tortured or otherwise ill-treated. Between September 2005 and July 2006, at least 303 people were convicted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms in 22 trials, all but one closed to the public. The government continues to seek out those whom it considers linked to the massacre.

Aftermath

Immediately following the Andijan massacre, the Uzbek government unleashed a fierce crackdown on human rights defenders, independent journalists, political activists, and civil society groups. Dozens of activists were imprisoned and others fled the country, fearing persecution. Over the last six years, Uzbek authorities have maintained this ruthless campaign against all forms of dissent.

In the years since the massacre, Human Rights Watch has continued to receive credible reports that local authorities intimidate and harass the families of Andijan refugees, summoning them for questioning, placing them under surveillance and pressuring them to convince their relatives to return to Uzbekistan. Uzbek authorities have persisted in persecuting anyone they suspect of having ties to the 2005 Andijan protest.

In a stark example, Diloram Abdukodirova, a refugee who fled Andijan in 2005, returned to Uzbekistan in January 2010 to be with her children after assurances to her family that she would not be harmed if she returned. She was detained upon her arrival, held for four days, and then temporarily released but taken into custody again in March. On April 30, 2010, she was convicted on charges of illegal border crossing and anti-constitutional activity and sentenced to 10 years and 2 months in prison. According to a family member, Abdukodirova appeared at one court hearing with a bruised face, raising concern that she had been ill-treated in custody.

EU Sanctions

On October 3, 2005, the EU imposed sanctions on Uzbekistan - which included a partial suspension of the EU-Uzbekistan Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, a visa ban on 12 government officials considered responsible for the massacre and/or the ensuing cover-up and crackdown, and an embargo on arms exports to Uzbekistan. The sanctions were accompanied by criteria set by the EU for reviewing its sanctions policy vis-à-vis Uzbekistan. Beginning in 2006, despite the Uzbek government's failure to take any concrete steps to meet the criteria, the EU began weakening the sanctions. In 2006, it re-instated the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement; in 2007, it suspended the visa ban; and in October 2009, it lifted the arms embargo - the last remaining, and largely symbolic, portion of the sanctions policy. Furthermore, starting in 2007, the EU dropped the call for an international investigation into the Andijan massacre from the sanctions criteria.

Uzbekistan's Human Rights Record

Uzbekistan's overall human rights record is abysmal. Torture and ill-treatment are used systematically in places of detention to coerce confessions. Muslims who practice their faith outside state controls are persecuted for their beliefs, with hundreds convicted on religious extremism charges every year, and many others re-tried on spurious prison violation charges to keep them incarcerated years after their original sentences are complete. Habeas corpus (judicial review of detention), which the Uzbek government claims is indication of an improvement in its rights record, fails to protect detainees against torture. The legal standard is weak, habeas hearings are closed proceedings and judges approve requests by prosecutors to arrest defendants in nearly every case. Judges also routinely ignore torture allegations.

Human Rights Watch has documented how civil society activists in Uzbekistan have been detained, beaten, placed under surveillance, harassed and imprisoned in retribution for their work. At least 13 human rights defenders are serving long prison terms on politically motivated charges. Several are in very poor health and at least seven have been ill-treated or subjected to torture in custody. Other activists, such as the poet and political dissident Yusuf Jumaev, are similarly serving long sentences on politically motivated charges.

The government clamps down on media freedoms and refuses to allow domestic and international NGOs to operate in Uzbekistan without interference. In March, Human Rights Watch announced that the Uzbek authorities had forced it to close its Tashkent office by persistently preventing HRW staff from receiving visas and accreditation over many years. The same week, Uzbekistan's Supreme Court informed Human Rights Watch that the Justice Ministry had initiated liquidation proceedings against its office in Tashkent.

The Uzbek government's record of cooperation with international bodies, in particular the United Nations, remains very poor. It has refused repeated requests by eight UN special procedures for access to the country: the special rapporteurs on torture; on the situation of human rights defenders; on freedom of religion; on violence against women; on the independence of judges and lawyers; on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; on contemporary forms of slavery; and the working group on arbitrary detention. It has also failed to implement recommendations from a range of UN expert bodies, such as the Committee Against Torture, the Human Rights Committee, and the special rapporteur on torture.

Widespread use of government-sponsored forced labor, including child labor, to collect the annual cotton harvest is a pervasive human rights concern in Uzbekistan. There is no evidence that the government has taken any meaningful steps to implement International Labor Organization (ILO) Conventions on the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor (Convention No. 182) or on the Minimum Age of Employment (Convention No. 138), which it ratified in March 2008, despite adopting a National Action Plan in 2008 and introducing legislative amendments in December 2009. The Uzbek government has rebuffed ILO requests to gain access for its independent monitors to visit Uzbekistan to assess the extent of its compliance with the international obligations it has undertaken.