(Brussels) - The Kosovo authorities need to work with international donors to close lead-contaminated camps occupied by internally displaced Roma without delay, relocate their inhabitants, and provide medical treatment for lead poisoning, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 68-page report, "Poisoned by Lead: A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Mitrovica's Roma Camps," tells the story of a decade of failure by the UN and others to provide adequate housing and medical treatment for the Roma, and the devastating consequences for the health of those in the camps.

"Roma have been stuck in these poisoned camps for a decade," said Wanda Troszczynska-van Genderen, Western Balkans researcher at Human Rights Watch. "How long would the UN and Kosovo officials put up with it if their own families were forced to live in a place like that?"

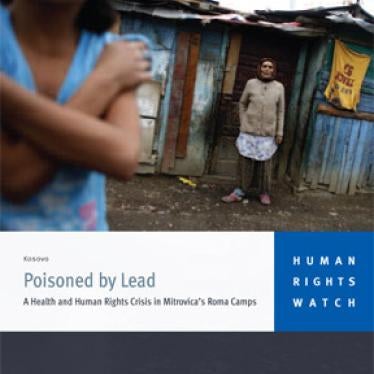

The Roma district in the northern city of Mitrovica was attacked by ethnic Albanians in June 1999. By June 24, the district had been looted and burned to the ground, and its 8,000 inhabitants had fled. Many were resettled by the UN in camps in a heavily contaminated area located near a defunct lead mine. The move was originally intended to be temporary, yet about 670 Roma still live in camps near the site, with damaging consequences for their health.

Despite the widely known high levels of toxicity in areas surrounding the defunct Trepca mine complex (first documented by the UN in 2000), all but one of the Roma camps are in close proximity to the slagheaps. The other camp is in Leposavic, 45 kilometers to the northwest. The location of the camps and the poor living conditions within them has damaged the health of the residents, especially children, who are vulnerable to extended exposure to lead.

"It is clear that lead contamination has damaged the health of people in the camps," said Troszczynska-van Genderen. "Children are especially badly affected, with some suffering from stunted physical and mental growth."

Small-scale testing for lead contamination and "chelation therapy" (treatment designed to remove lead from blood), carried out by doctors and nurses, took place a few times between 2004 and 2007, focusing on children. The testing and treatment were coordinated by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo and the World Health Organization. But no comprehensive testing and treatment has ever been carried out.

In 2007, the UN Mission decided to halt treatment, and testing was discontinued after the erroneous conclusion (based on the assumption that the Roma would be soon moved out of the camps) that it was no longer required. Subsequent testing by the north Mitrovica hospital, requested by camp residents, indicated that some children continued to have dangerously high levels of lead in their blood. Excessive lead levels in the human body can cause damage to the nervous and reproductive systems, as well as kidney failure. Very high lead levels result in coma and death. Lead is particularly harmful to children, as it can cause irreversible brain damage.

There was almost no attention to the health emergency in the camps until 2004, when local and international Roma activists began to raise concerns in the media, and sought to force action through (ultimately unsuccessful) legal challenges in the Kosovo courts and at the European Court of Human Rights.

In 2006, after pressure from United Nations human rights bodies and nongovernmental organizations and critical media coverage, the UN mission closed two of the three most contaminated camps, Zitkovac and Kablare. Around 450 residents were helped to return to their homes in Mitrovica, while others were moved to another temporary camp (Osterode). The new temporary camp, 150 meters away, is heavily exposed to toxins carried by wind coming from lead slagheaps, but authorities claimed that it was "lead safer" because its concrete surfaces and running water mitigated the lead contamination.

The third camp ("Cesmin Lug") remained, with its inhabitants reluctant to move to the new temporary camp because it was still in the area of contamination.

Little has been done in the last decade to assist the Roma who remain in the camps to leave and find permanent homes, either by returning to their former homes in Mitrovica or elsewhere. Some Roma returned to Mitrovica in 2007 when two camps closed, but found they did not have access to jobs or to Kosovo welfare assistance there, and therefore had no means of support.

In May 2008, as the UN mission prepared to downsize its presence in Kosovo, it handed over management of the remaining camps to the Kosovo Ministry of Communities and Returns, which has no strategy to tackle the crisis. In addition, the camps are located in a municipality under the control of ethnic Serbs, who do not accept the jurisdictions of the new Kosovo government, led by ethnic Albanians.

The Kosovo authorities recently established a coordination group, led by the prime minister's office and including the US and European Commission, to develop a plan to tackle the crisis. But much more work, including greater financial and political support from major donors and a stronger focus on medical testing and treatment, will be required to turn the idea into reality.

"After 10 years, it's about time we had some momentum to solve this problem," said Troszczynska-van Genderen. "It is vital that the US and EU work with the authorities in Kosovo, including in Serb-controlled municipalities, to solve the crisis."

Human Rights Watch recommends that the Kosovo authorities and international donors act to organize a long-term solution including:

- The urgent medical evacuation of current camp residents to acceptable temporary housing;

- The permanent closure of the remaining camps;

- Urgent treatment for lead contamination for all current and former residents;

- A long-term housing solution based on the wishes of the residents; and

- Access to welfare, medical treatment, education, and employment.